“The sole purpose of your life from birth to death is to become a part of that endless and timeless cosmic creativity.” –David Anderson

Among artists, JMW Turner (British, (1775–1851) is especially revered for his wild use of atmospheric light and dramatic weather effects. Of course, Turner didn’t use them just for visual interest, though – far from it. For Turner, whose work helped to define the Romantic Movement, painting was both an instrument of imagination and feeling as well as a mirror of his time. These aspects of his work channelled feeling into his canvases.

It’s interesting to art historians that many of Turner’s stormiest, most apocalyptic paintings contain references to the technology of his moment in history, the “steam age” that was part of the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. He knew he lived on the cusp of a momentous shift from the old world’s pastoral, agrarian way of life to the modern industrial economy of coal, factories, and steam engines. We know this because he reflected this insight in his work.

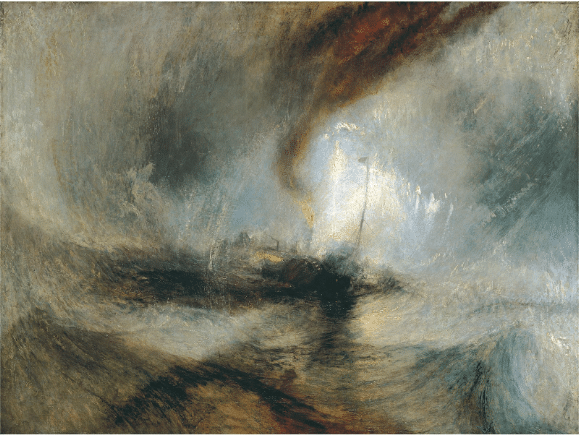

In many of his late paintings, Turner used vigorous brushstrokes and loosely defined forms to explore dramatic struggles between human beings and the elements. Tapping into the Romantic mode of the sublime, in which overpowering natural forces dwarf humanity, Turner elevates the human condition to cosmic proportions. “Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbor’s Mouth” (top of page) becomes a swirl of chaos, sea and sky near lost in each other and man at the mercy, as if the universe itself has become a vortex, “a hyperborean winter scene … the unnatural combat of the four primal elements,” as Herman Melville described it.

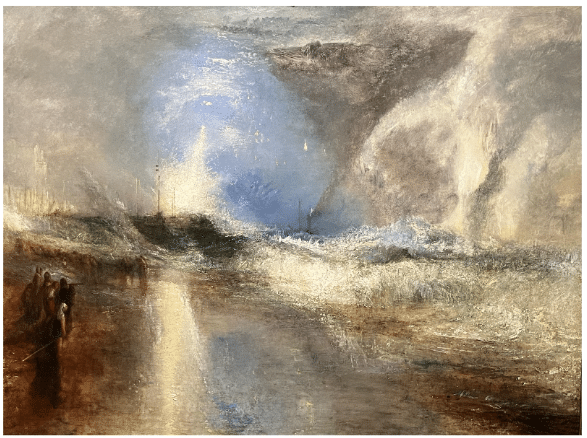

That painting resides at London’s Tate Museum, but the Clark Institute in western Massachusetts has another sublime Turner with similar elements, the “Rockets and Blue Lights (Close at Hand) to Warn Steamboats of Shoal Water” of 1840. (Below)

JMW Turner, “Rockets and Blue Lights (Close at Hand) to Warn Steamboats of Shoal Water” oil, 1840. Clark Institute, Williamstown, Mass.

This work shows a storm raging in an English harbor town. Flares explode in the sky to alert ships to the location of shallow (shoal) water.

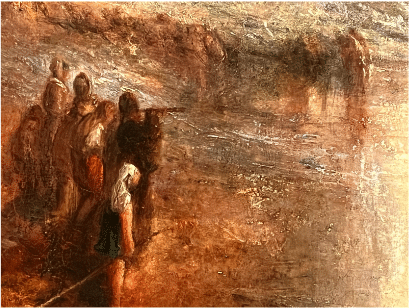

Detail, lower left. On the shore huddled spectators stare out to sea, perhaps anxiously hoping their loved ones will survive the storm and return safely home.

The falling “rockets” (flares) seem disproportionately large, rather like giant fireballs, as if the sky itself were falling. Off in the distance the steam-boat with its smokestack flaring, seems a vulnerable outpost of humanity in a cosmic drama taking place on a monumental stage.

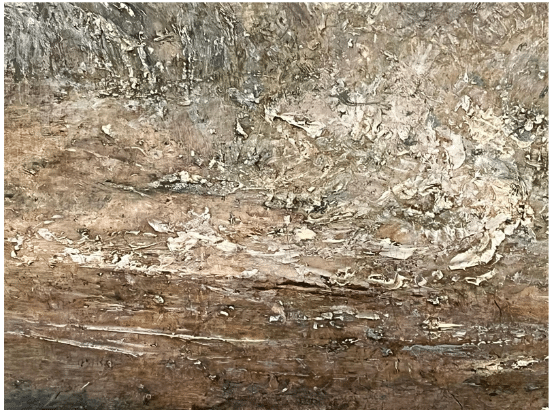

In the closeup below you can see Turner’s use of thick, ragged paint marks to convey the water’s agitation.

detail, Turner’s impasto sea churn.

Turner’s prophetic visions of industrial humanity at odds with angry Nature furnished the subject of a 2022 exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, some great images from which you can dig into online here.

And if painting the drama of the sea is something you’d like to learn how to do, check out these professional instructional videos here.

Alexander Dzigurski II, Evening Fire at Nepenthe, oil. 30 x 40 in.

Two Must-See Watercolor Exhibitions

By Kelly Kane

Handled With Care

Barbara Prey draws inspiration from Shaker master crafts.

Barbara Ernst Prey (b. 1957), “Red Cloak Blue Bucket,” 2019, watercolor and drybrush on paper, 28 x 40 in.

It’s been 250 years since the United Society of Believers, more commonly called Shakers, arrived in America from England. They made by hand most of what they needed — tools, baskets, tubs, cleaning and measuring devices — and sold those items to the outside world.

A leading repository of their creations is Hancock Shaker Village (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), which in 2018 invited artist Barbara Ernst Prey to create 10 large watercolors of anything on its property that engaged her attention. She has loaned six of the resulting works to NBMAA’s show, which also features items from Pittsfield that all have handles and have survived in good condition.

The New Britain Museum of American Art (NBMAA, Connecticut) is presenting the exhibition “Handled with Care: Shaker Master Crafts and the Art of Barbara Prey” through October 6, 2024.

Birds and Beasts of the Studio

In a series of studies and watercolors Walton Ford imagines encounters between big cats and humans, largely based on true stories.

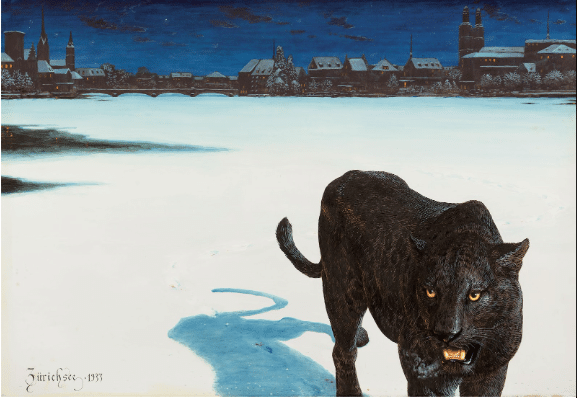

Walton Ford, (b. 1960), “Zürichsee,” 2015, watercolor, gouache, and ink on paper, 41 1/2 x 59 3/4 in., private collection; photo: Christopher Burke

Walton Ford is renowned for monumental watercolors that reflect his fascination with how we imagine wild animals, often subverting the historical conventions of animal painting in unforgettable ways.

An exhibition currently on display at the Morgan Library & Museum opens with works inspired by Ford’s decades of visits to the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan. To this day, Ford explores that institution’s rich archives, field studies, documents, and taxidermy specimens. The drawings confirm that his artistry is rooted in scientific research and an attention to detail.

Particularly compelling are the sections of the show devoted to Ford’s studies and watercolors that imagine encounters between big cats and humans, largely based on true stories. Illustrated here is one in a series about a black panther that escaped Zurich’s zoo and spent weeks alone in the countryside before being caught and eaten by a farmer.

Also on view are books Ford has loaned, from travel diaries to volumes of natural history, folktales, and fables. The exhibition closes with a display of relevant pieces selected by Ford from the Morgan’s holdings, accompanied by wall texts he has written. It includes memorable images of animals created by such masters as Rembrandt, Audubon, and Delacroix.

The Morgan Library & Museum in New York City is presenting “Walton Ford: Birds and Beasts of the Studio” — a celebration of the American master’s 2019 gift to the Morgan of 63 studies and sketches, now shown publicly for the first time. It will be on view through October