It’s said the triangle is the most stable of geometric forms. It’s the most heavily weighted in terms of base vs. height, and therefore is said to evoke stability and balance, a sense of assurance and calm. This is a function of the equal distribution of visual weight. (The forms in any given composition have a certain “weight” in terms of how they “pull the eye” from one place to another.)

In a pyramidal or triangular arrangement, either forms assume the shape of a three-sided figure or visual weight is more or less evenly distributed among various elements that definitely relate to one another in a triangular, or “triadic,” arrangement.

Why it works for any subject has to do with the angles and placement of the lines. It automatically keeps the eye moving (and within the picture frame, not pointing out of it) by leading the viewer up, then down, and across the canvas, and on and on. If you vary the placement and proportions, or combine the pyramid with other designs in the same painting, you can use this compositional device all over the place without it becoming obvious or repetitive from one painting to the next.

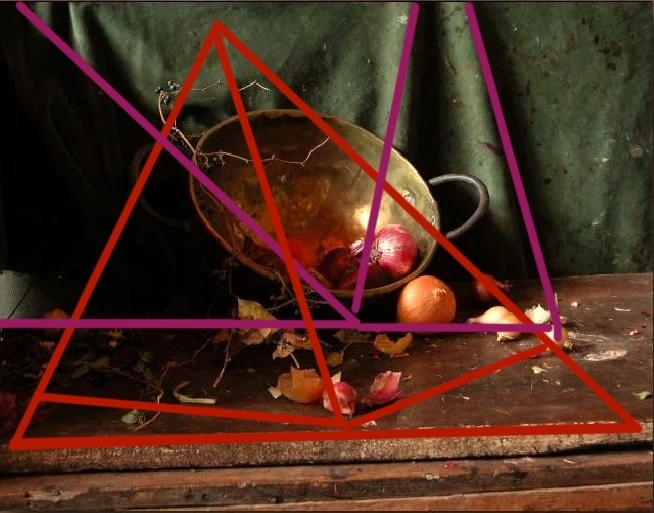

Sherrie McGraw uses what amounts to a pyramid composition in Still Life with Onions, which is the subject of a detailed teaching video that you can purchase here.

Pyramid compositions work particularly well for bowls of fruit, waterfronts with boats’ masts, gabled houses and barns and figural groups, but you can use the pyramid composition to create a strong balanced design for any kind of subject, portraits and landscapes included.

An example of a strong yet complex use of the device comes from French Neoclassical painter Gericault, who in turn was responding to Rembrandt’s Storm on the Sea of Galilee (stolen from the Isabella Stewart Garner Museum of Art in the 190s). In Rembrandt’s earlier, off-kilter pyramid, the point on the left gets spotlighted as the focal point, where the eye goes first. Tilting up the otherwise stable geometric base emphasizes the violent tossing motion and height of the dangerous swells as well as the contrasting enveloping darkness.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Storm on the Sea of Galilee, oil, 62″ x 50,” 1633 – an example of a classic pyramidal composition

Note that we are dealing with a pyramid in this painting, not a triangle. The same is true for Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa.

Both artists managed to simultaneously make use of and subvert the stability of the pyramid.

Gericault has literally one-upped Rembrandt by adding an additional, overlapping pyramid. While both artists skewed their pyramids for tension, Gericault effectively pulls pyramid one out of the other and points the two peaks in contrasting directions.

Jean Louis Theodore Gericault, The Raft of the Medusa, 1818-1819. Louvre.

Gericault cleverly exploits the three-dimensional aspect of the pyramid’s geometry to make it impossible for his viewers to ignore the grim fate of his shipwrecked sailors. Gericault tilts the bottom half of the picture plane forward as if emptying his dead and dying castaways right into the viewers space; he thrusts his subject toward us, making us become part of it, as if we are standing on (or falling off!) the the projecting corner edge of the waterlogged raft.

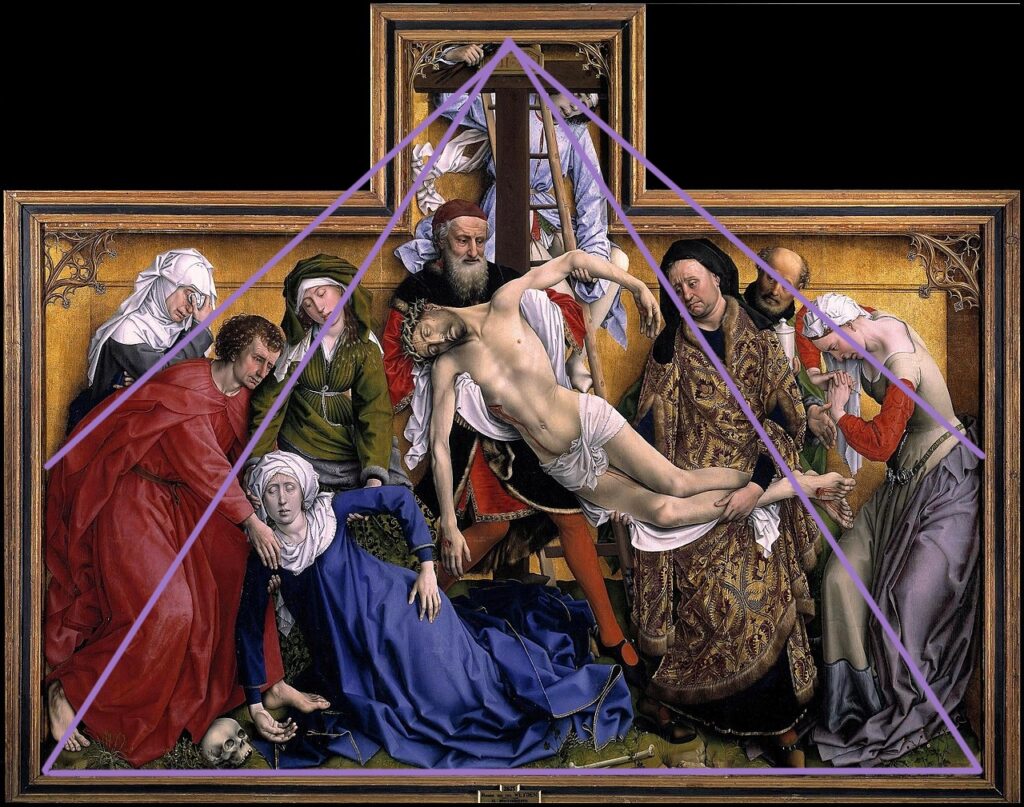

Having three sides, the triadic composition seemed a natural choice for Christian art; in church commissions, the symbolism of the holy trinity or holy family motif found visible form in three-sided geometry. Furthermore, with its pinnacle pointed toward Heaven, the pyramid or triangle also suggested aspiration toward the Divine paired with the base’s evocation of the foundational stability of the Church on earth.

Renaissance painters like Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael and later history painters used it repeatedly for their Madonnas and Christs on the cross.

Van der Weyden, Descent from the Cross, 1430

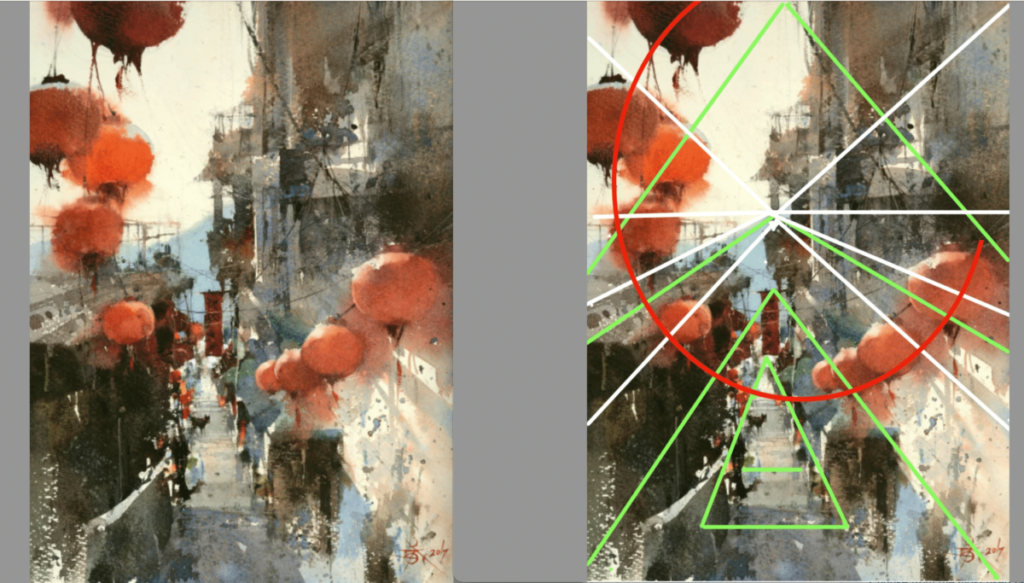

The painting below, by watercolorist Chien Chung Wei, is based on one-point perspective, with the vanishing point very close to the center of the composition (white lines on the diagram). However, the mountain’s centered peak and the stacked symmetrical diagonals arrayed in relation to it (as well as some subtle horizontal (base) shadows running across the canal) contribute to the sense of a pyramid structure in the lower half of the painting.

However, the stunning overlay of an expansive spiral (in the red paper lanterns) explodes the visual space and sets it all in motion. (To my eye, it creates an underlying structure that resembles a ferris wheel, but that’s beside the point.)

Chung-Wei treats making a painting like building a house; he starts from the structural design, moving on to the laying of the ground floor in a large area, and works on up toward the finishing details. Author of the book The Intrigue of Form, he’s a master of using composition to shape the viewer’s’ experience of a painting. Yes, he has a distinctive command of light and shadow (and subtle color dynamics), but he insists, rightly so, that it’s what’s under the surface of the painting that really counts. “Light in a painting is like the sugar coating on a pill,” he says. “It makes it go down. But it’s the composition that is the real medicine.”

If you’re looking to boost your skills at composition (or watercolors, for that matter) dive into Chung-Wei’s video or one of these other titles on composition and design that will definitely improve your eye and go a long way to help you make your best paintings.

John MacDonald, Charlie Hunter to show in American Tonalist Society Biennial at Salmagundi

John MacDonald and Charlie Hunter will exhibit work in the American Tonalist Society’s second Biennial Exhibition, DShades of Gray II, and the Salmagundi Club in NYC, April 29 – May 7, 2023. Tonalism is the art of using a limited color range while maximizing expression through atmospheric “color tones” or dark-light soft-edged value-shapes. Both artists have videos you can check out here.