Some artists can fall in love with their creations. Many others dislike looking at old work. Some never so much as glance back, and no sooner do they finish a painting than they’re already sketching out the next.

People have been thinking about the relationship between makers and the things they make ever since we as a species started making anything at all. Several classical myths address this idea, but one that has a happy ending is the Roman story of Pygmalion and Galatea. In this one, a man creates an inanimate object – a sculpture of a woman – that not only comes to have a life of its own but falls in love with him (or, technically, loves him back).

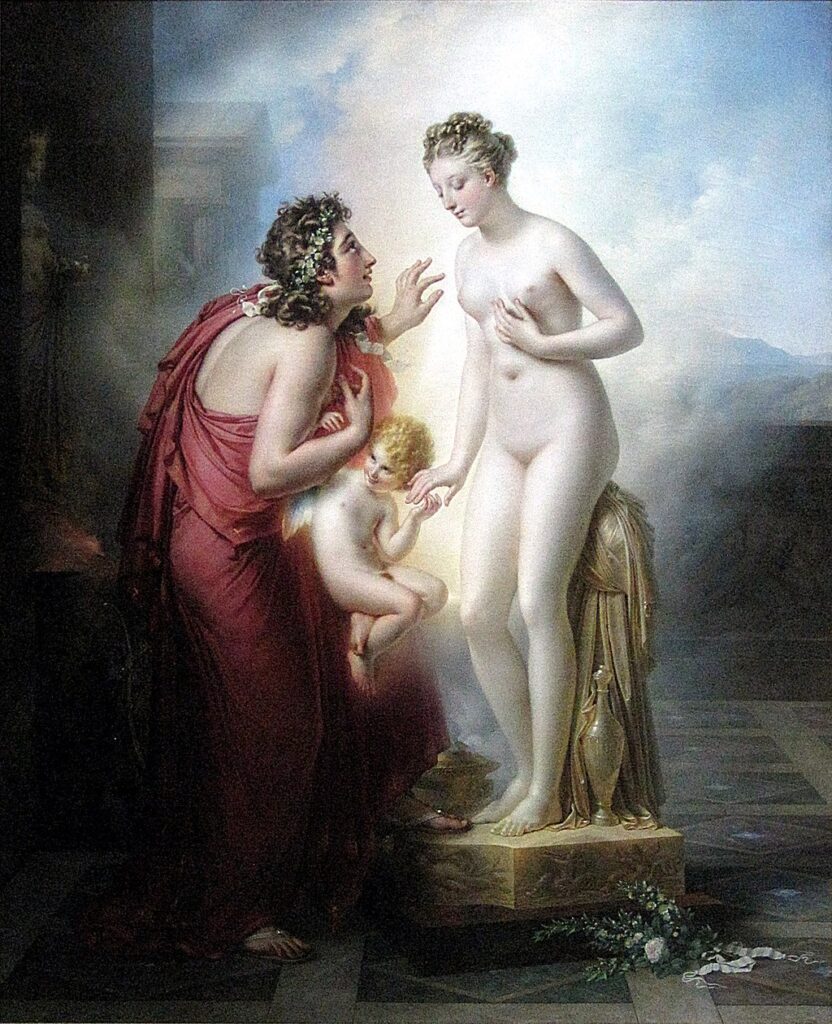

Pygmalion taken by surprise as Venus gives the touch of life to his statue, by Jean Raoux, 1717

Ovid says Pygmalion was an artist so uninterested in his hometown girls that he sculpted his own image of ideal purity and beauty and hid her away in his studio. He named the sculpture Galatea, and every day he grew fonder and more enamored of his creation. Seeing the pathetic, lovesick artist kissing and caressing his statue, Venus took pity on him and brought Galatea to life in his arms.

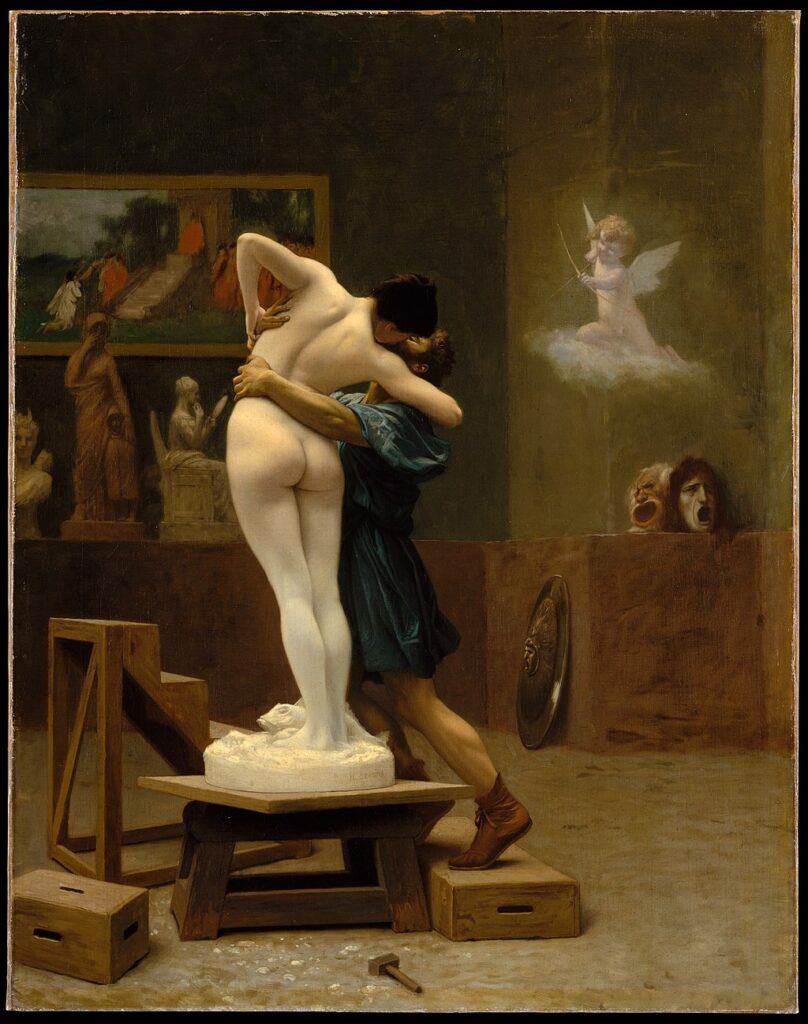

Pygmalion and Galatea, Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1890, Oil on canvas, 89 cm × 69 cm (35 in × 27 in)

Most myths like this end badly (we shall all suffer terribly for what the gods have given us, warned Oscar Wilde). This time, however, the mortal gets away scott free. Love blossomed between Pygmalion and Galatea, and it wasn’t long before wedding vows were exchanged, with the Goddess of Love in attendance, blessing them with prosperity and happiness all their days. The happy couple eventually had a son who founded an important city as well as, some say, a daughter of surpassing beauty, talent, and charm.

Anne-Louis Girodet De Roussy-Trioson, Pygmalion and Galatea, oil, 253 cm x. 202 cm.

Nearly all the famous paintings of this myth employ the “portrait” format, emphasizing the verticality of Pygmalion’s sculpture. They also have in common that the woman is literally placed on a pedestal, and therefore stands higher than Pygmalion, who must look upward to see her face. In nearly all, the artist goes for the moment in which Galatea is coming to life, meeting the challenge of depicting one half of the figure in solid stone and the other in glowing flesh.

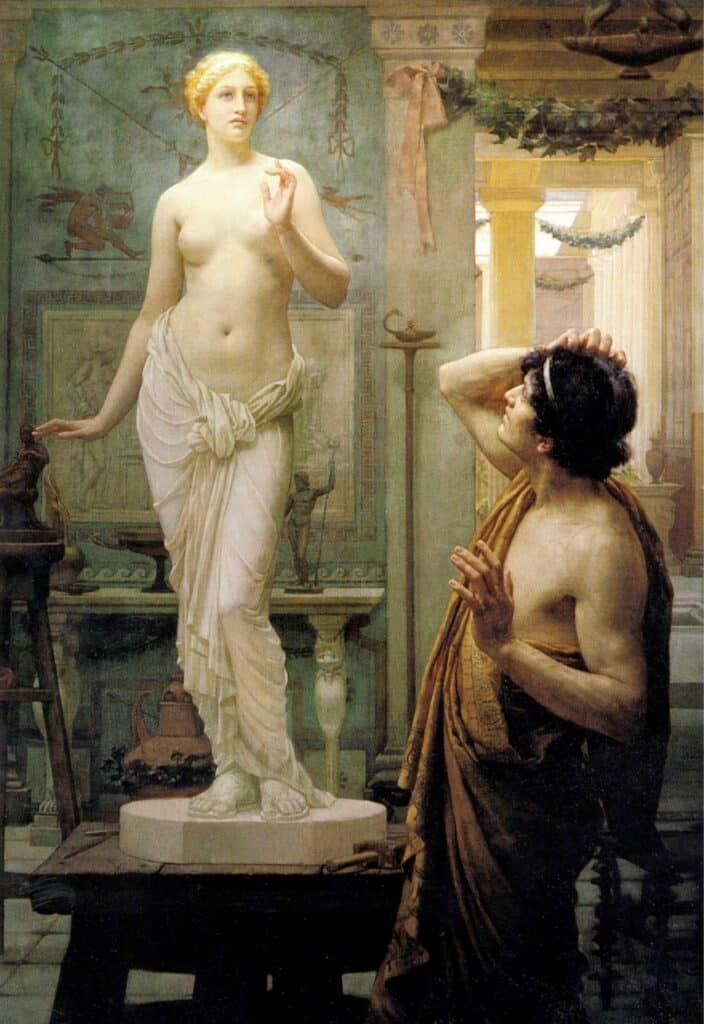

Pygmalion and Galatea, Ernest Normand (1857–1923), 1886

Most depictions show some measure of astonishment on Pygmalion’s part regarding the startling turn of events, and yet they usually suggest the union will be a happy one. Victorian English artist Ernest Normand, however, departs a little from these conventions. In his 1886 rendering (above), Galatea stares fixedly off into space like the blank slate, devoid of memory or identity, that she is. Meanwhile, Pygmalion reels, taken aback, his right hand instinctively holding onto his mind-blown head. Normand’s oil is a strange and beautiful mixture of realism and fantasy.

But in the end, that is what most myths are anyway, no? And aren’t all artists at least somewhat like the Englishman’s Pygmalion? Aren’t we all a bit like Normand’s bewildered maker, more or less at odds with the creative process, and ultimately uncertain whether to feel love, distaste, or astonishment at how sometimes – if only sometimes – our creations seem just about to come alive, miraculously, as if with a life of their own?

If you’re looking for paintings in the classical tradition that virtually bring the figure to life, you can’t go wrong with Cesar Santos. If you’re passionate about figure painting and want to learn how the great masters painted, you might want to download Cesar’s video, Secrets of Figure Painting and get to work.

|

|