When people talk about “poetry,” “atmosphere” or “mood” in landscape painting, they usually mean an evocative quality that prioritizes feeling and mood over accuracy of detail. Favoring mystery over precision and clarity, such paintings imply more than appears on the surface, drawing the viewer, through suggestion and imagination, into the painting’s “other world.”

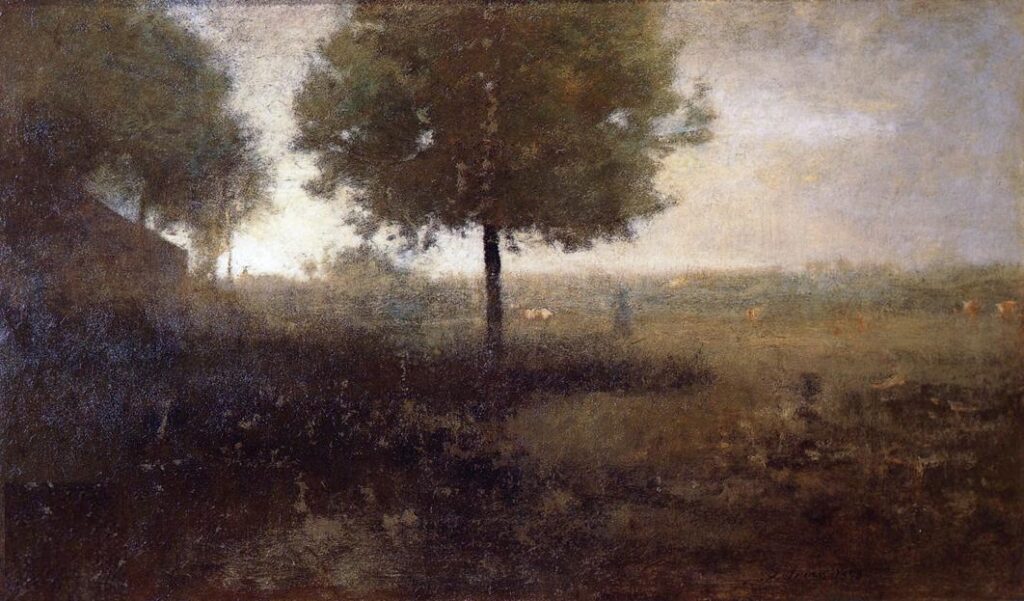

George Inness, Hazy Morning, Montclair, New Jersey, 1893

Though at a glance this painting may look like just another Barbizon-inspired landscape, It’s a painting of “ordinary” American scenery (little is overtly “majestic,” sublime or Romantic about its subject). And yet, it works a subtle magic, quietly captivating the viewer through harmonious, saturated earth tones, a composition designed to instill a sense of secretly ordered life and movement. There are strong primary (and secondary) “points of interest,” yet they’re positioned within a kind of unifying indeterminacy, infused with a mystical haze that results from lost edges, close color harmonies, and brushwork that’s loose, yet graceful and disciplined. The lone figure (visible under the tree) might as well be a ghost.

In such mid-career and later works, Inness doesn’t copy nature; he opens it up for us to re-imagine, so that we can’t help becoming intuitively involved in completing his subjects out of the flickering stuff of memory, imagination, and desire.

Inness is not being “Impressionistic,” a style he could never embrace. Rather, by building indeterminacy (uncertainty where one thing begins and another ends) into familiar, cultivated scenery, the effect is as if he is painting the here-and-not-here of two worlds, one of illusory reality and the other of mystical experience, both embodied in the everyday, and both beautiful. And yet, he fully articulates certain key objects. A fallen log, for example, he might delineate through spot-on shape, value, and color. Burt overall, these late works conjure a beauty that is holistic and visionary, tapping into a spiritual essence that seeks a connectedness to the natural world that reaches beyond mere fact.

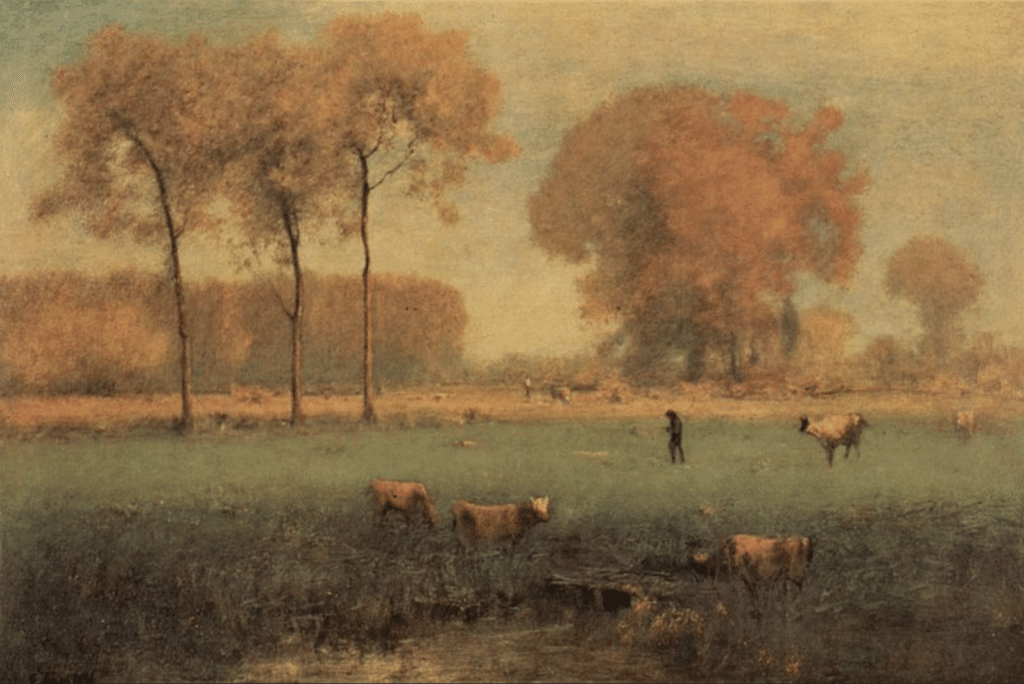

George Inness, Montclair, 1891

For me, Inness is the Spirit Painter of nineteenth-century America. His trees are like spirit-fountains of intriguing color and mood mediating between earth and heaven. For Inness, to apply the central concept from Swedenborg, the beautiful geometries of the world are “correspondences” that mediate between our blind mortal life and a vision of eternal Spirit.

George Inness, Summer Landscape, 1894

George Inness, George Inness, “Moonrise,” 1891

Mary Garrish, “Quiet,” oil on linen, 16×16 inches

If you are interested in the Tonalist style of painting that Inness’s work gave birth to, check out Mary Garrish’s Tonalism. This video contains everything you need to know about Tonalism and how to paint in that style. Tonalism has tons of benefits for any artist because it can help you improve your understanding of values and colors, two key elements in any successful painting.You’ll also discover how Tonalism can enhance emotions in your paintings, and how you can do it too using simple techniques that Mary will share in this video.

“You’ve Got to Do It”

By CherrieDawn Haas

Alongside the rippling Clear Creek in Golden, Colorado, a group of tour buses paused to unload determined plein air painters – some of painting on location for the first time in their lives. They weren’t alone, though, because faculty and field painters by the score from the 10th Annual Plein Air Convention & Expo (PACE) were there to guide them.

“You’ve got to do it,” a friend told Trina Campbell, who was experiencing plein air painting for the first time with us. Trina shared with me that she’s starting a new chapter in her life, and painting is a big part of it. She invested in not only her PACE ticket and trip but also the gear that will support her art journey. “I’m super glad I made the decision to do this,” she said, adding that from the time she arrived at PACE, others were offering helpful advice and support. “I feel it was the best decision to make, for sure.”

Continue reading here.