“Steal like an artist.”

That’s the title of a popular self-empowerment book for artists and a phrase on lots of peoples’ lips these days.

It’s a variation on “Good artists borrow, great artists steal!” which is excellent, even though it’s misattributed sometimes to Picasso and sometimes to T.S. Eliot. It actually comes from Eliot (substitute “poets” for “artists”) but not in those words. What T.S. Eliot said is the following and I’ll tell you why it’s worth quoting the whole passage in a minute:

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.

So “good artists borrow, great artists steal” is not about “good” or “great” in the original – it’s about beginners (“immature”) vs. experienced (“mature”). It’s also not about copying other peoples’ work. What Eliot meant by “stealing” as opposed to “imitating” is don’t settle for painting the same paintings in someone else’s style – do that, but then take that style and make it into something better, or at least different. We know this as “making it your own.”

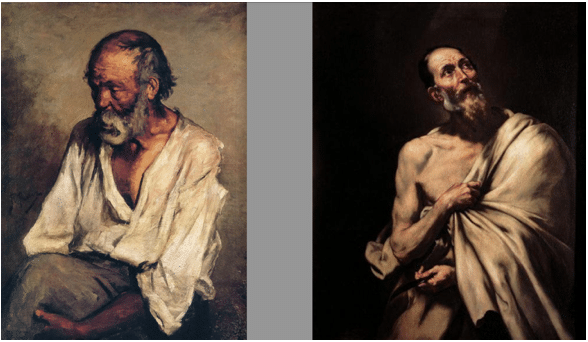

In fact, it’s actually a perfectly good idea to copy other peoples’ paintings when you are starting out – it’s one of the best ways to learn to make the kind of work you’re interested in making. Just don’t copy the signature, make the painting in a different size, and no harm no foul. This is something classical artists’ apprentices and Academic students of painting did for hundreds of years – because it works.

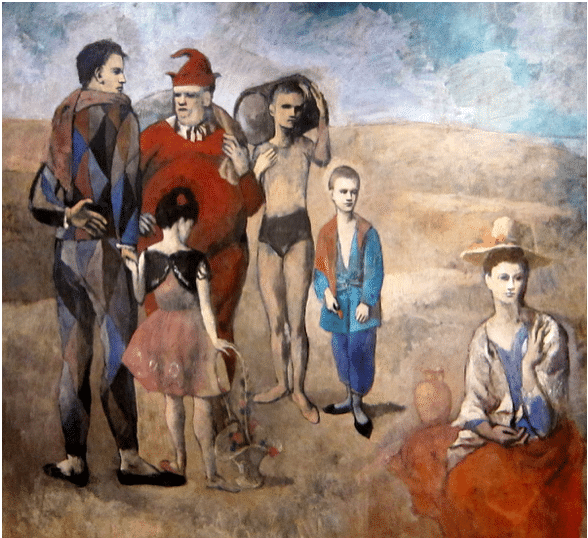

What Picasso actually said, by the way, amounts to (I’m paraphrasing) Go ahead and try to imitate someone else! You can’t do it! And when you find out you can’t 100 percent do it – when you have to start making it up? If you’ve got the goods, that’s when you start to find your own style.

An early painting by Pablo Picasso, The Old Fisherman, 1895. RIGHT: Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Bartholomew, 1791.

“What does it mean,” says Picasso, “for a painter to paint in the manner of So-and-So or to actually imitate someone else? What’s wrong with that? On the contrary, it’s a good idea. You should constantly try to paint like someone else. But the thing is, you can’t! You would like to. You try. But it turns out to be a botch…. And it’s at the very moment you make a botch of it that you’re yourself.”

No artist works in a vacuum. Everything we paint is conditioned by everything we’ve done, thought, felt, and seen, including and especially the art of the past and present and rightly so. I think what all this is getting at is that the ultimate goal, whether we’re talking about realism, abstraction, copying, or improvising, is to try to somehow free yourself enough to produce art that is yours because it comes from you – but you can’t do that effectively without starting with what’s already been done. First learn the technique, so that in the heat of working you can forget all about it and just GO.

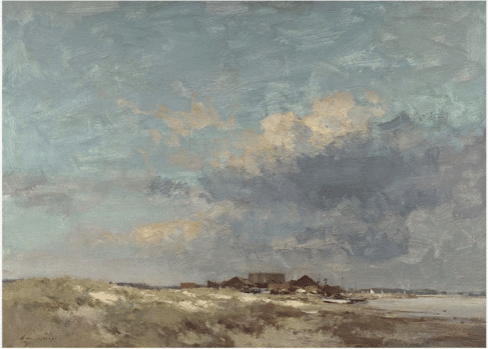

Below you see a painting by Edward Seago, a 20th century British landscapist. I love how loosely he paints everything yet how true he is to the nuances of tone, color, and temperature. The brushstrokes (or “marks”) in his paintings often form an abstract pattern on their own that contributes harmoniously to the overall mood and impression of the work.

Here, the brushstrokes and mark-making form their own self-contained abstract pattern that contributes to the vibrant sense of breeziness, air, and shifting light and shadow at the heart of the work (most clearly visible in the empty area of the upper sky).

Edward Seago

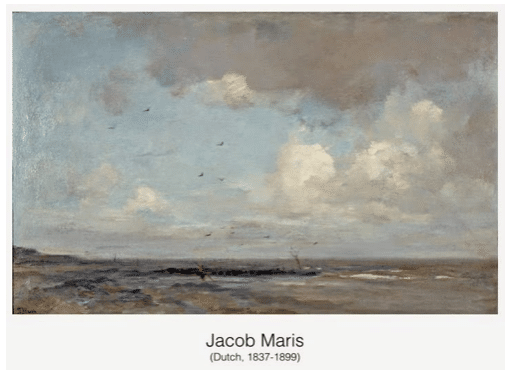

But Seago owes his palette and even his composition to earlier Dutch artists. Below is a painting by Jacob Maris that contains many of the same elements that Seago’s painting does only in a different configuration: common to both paintings is the typically Dutch division into a small strip of land and a big sky patterned and set in motion with lively brushwork, bright, blowsy clouds composed of patches of warm pigment beside warm blues offset by cool mauves and grays, neutralized green-grays and violets for the foreground and middle-ground land, as well as the overall sense of scale.

The point is not that Seago copied or “imitated” Jacob Maris. He stole from him, of course, as all good artists do from their masters. And Maris himself was one of scores of painters who worked off paintings made another 200 years earlier than that, by Dutch masters such as van Ruisdael. Below, in the earlier Ruisdael, despite the obvious differences to Maris, we see the same sense of scale, same sky-to-earth ratio, and a similar use of understated chiaroscuro, earth colors, and diffused light.

Jacob van Ruisdael (1628-1682)

If you’re just trying to find your style, it’s best to avoid getting hung up on questions of influence vs. plagiarizing or derivation. Be honest with yourself and your viewers. Take whatever from everywhere, and know that eventually it’s how much compelling interest, joy, and imagination, how much of yourself that you get into the work that will count.

“Copiers don’t bother me,” Picasso declared, “If they have any temperament, it’ll appear eventually to disclose the personality of an artist… It is better to copy a drawing or painting than to try to be inspired by it, to make something similar. In that case, one risks painting only the faults of his model. A painter’s atelier should be a laboratory. One doesn’t do a monkey’s job here: one invents. Painting is a jeu d’esprit.”

Interested in learning the techniques of classical portraiture and figure painting, such as that practiced by the young Picasso and Ribera? Then check out Secrets of Expressive Portraits by Tony Pro (which is more than half of at the moment).

Demo: Painting a Herd of Cows, Step by Step

The following is part of a series featuring a leader in the art community who will be joining us on the faculty of Pastel Live, a virtual art conference taking place August 17-19, 2023.

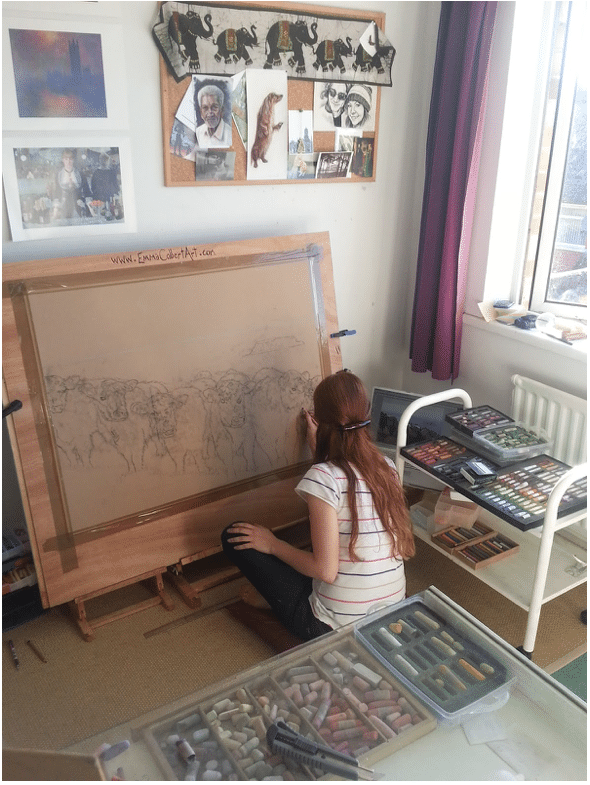

“I work in a realistic style but always aim to create a painting with more depth and vibrance than the photo reference,” says Emma Colbert. “I spend my time working on people and pet commissions, as well as my own series of wildlife and landscapes.”

Here’s how Emma painted a large pastel of these cows on a ridge in Ireland.

Step-by-Step Demo of “The Belties”

By Emma Colbert

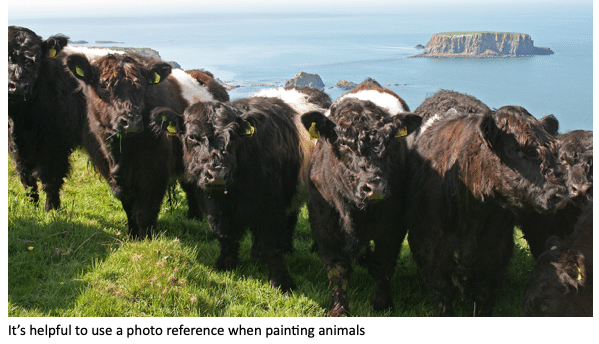

1. I went to photograph these gorgeous animals at their rural home on the North Coast of Ireland. The backdrop and lighting were just as they were on the day, fresh! This is the reference photo I took. I had very little to change; I liked how a couple of cows were cut in half and I just removed the cow on the bottom right as I thought he didn’t add anything.

2. I sketched this out smaller and used a grid to help with the initial masses. I don’t mind having to use a grid when it’s something this complex. It certainly speeds this part up a little as I can get proportions a little easier. While good drafting is important I like the actual painting process the most.

….

Follow along with Emma and read the complete article online here.