It must have come to him in a flash: thoroughbred horseracing was The Perfect Subject for his new style and approach to painting.

It fit his friends, the Impressionists’, new mission for art: to paint everyday life at its most colorful and spur-of-the-moment. In fact, capturing the complexity of racehorses in motion ticked all the major boxes shared by Monet and Renoir:

- It was a fresh, seemingly unscripted response to the outsized fluster and flash of modern industrialized society starring the newly moneyed leisure class.

- It outdid the new art form of photography (by including the camera’s ability to crop out slices of reality yet winning because … color).

- And there was a whole long, stuffy tradition of horses in paintings for Degas (a total rebel as experimental as could be) to smash.

Impressionism was in part a reaction against the heavy-handed drama and self-aggrandizement within Academic painting of the mid nineteenth century. Take as an example of the latter, the Trumpeter of the Hussars (1816 -1820), pictured below. This approach is typical of the previous generation of French painters.

Theodore Gericault Trumpeter of the Hussars, c. 1815-1820. Oil.

Painted by French Neoclassical Academician Theodore Gericault (1791-1824), the figure’s uniform identifies him as a member of the Hussars, a notoriously fierce cavalry in the French Army. The composition is that of the standard military statue, usually meant to convey grandeur and patriotism. (However, some critics say the fact that this figure is in shadow, not sounding his horn, and in fact doing nothing heroic at all but standing far from the heat of the battle, speaks to the widespread disillusionment with the French military after the fall of Napoleon in 1815.)

Degas’ horse paintings are everything the Neoclassicist’s are not: spontaneous, unstaged, not freighted with any moralistic or political message. Where the Neoclassicist centered his image according to formal principles of beauty and proportion (e.g., the Golden Ratio), Degas deliberately disrupts the balance.

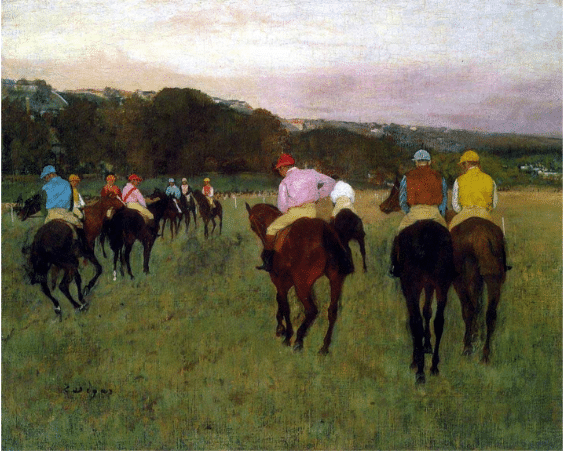

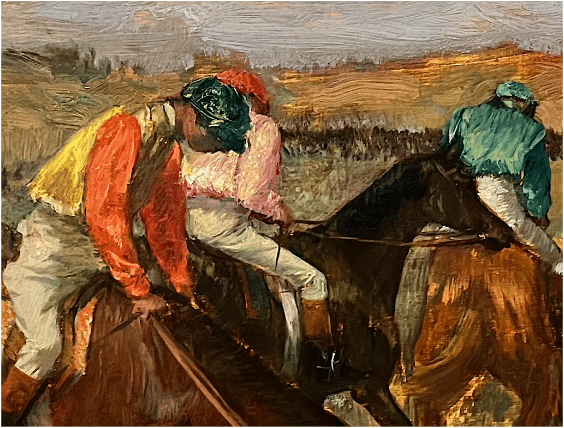

In Before the Race (below) from the Clark Museum in Massachusetts, one rider is all but cropped out of the left side of the image (a nod to contemporary photography). Another jockey is isolated from the rest, far off to the right looking outside the frame, and the others are clumped together in a complex, though seemingly random, overlapping arrangement. All face in different directions.

Edgar Degas, Before the Race, c. 1882, oil on panel.

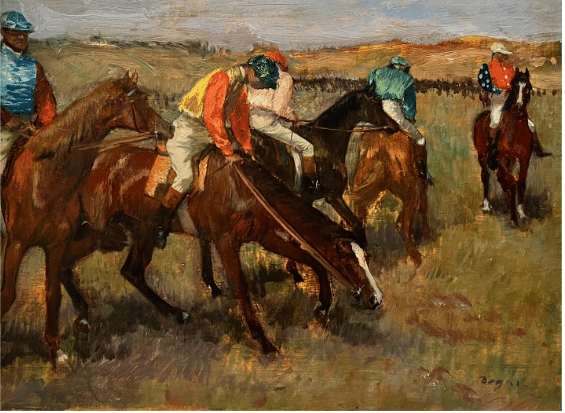

Where Gericault strove to erase any trace of the painter’s hand, Degas laid his paint upon the canvas with lush and loving abandon. In the closeup (below) you can see the brushstrokes and the various directions they move in, from the horizontal strokes in the background to the vertical, diagonal, and curving strokes in the colorful jerseys, helmets, and horses.

Edgar Degas, Before the Race (detail)

Note: Degas didn’t paint loosely because it is somehow “good to have visible brushstrokes.” Rather, such an “unrefined,” shockingly “crude” approach helped distance the artist from Neoclassicist obsessions. The vigorous brushwork conveys both the unstuffy immediacy of the Impressionist vision and the captive, restless energy of the moment at hand, “before the race.”

Though he was an enthusiastic visitor to the racetrack, Degas avoided pandering to the expected imagery of the sport. Instead, most his paintings of racehorses and jockeys, like those of his backstage or practicing ballerinas, are more like snapshots, taken off-track in the less glamorous, grittier moments before and after, rather than during, the races.

Overall, Degas chose a very modern, contemporary scene and depicted it precisely as it presented itself to his alert and observant eye. He met photography’s challenge by stealing what seemed expressive and modern about it – its way of capturing the moving parts of a world seemingly moving faster than ever – and showing that painting could do just the same and more.

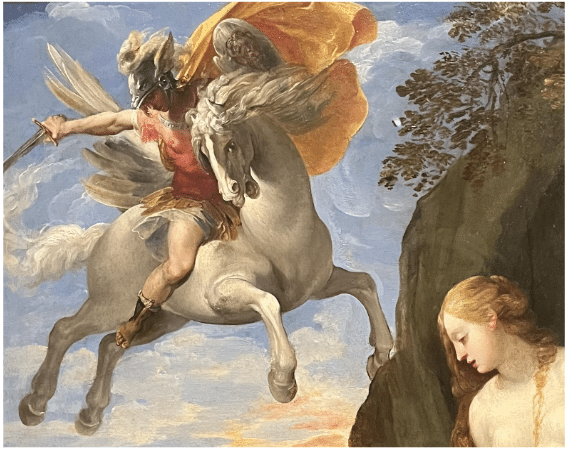

And he helped invent modern art by defying art history. Here’s a typical Baroque horse by an Italian named d’Arpino, who painted it in the 1500s – it’s Pegasus, on which Perseus rides to rescue the Princess Andromeda. Lucky d’Arpino – by making his horse a flying one, he weaseled out of the complexities required to paint them as they really are. D’Arpino’s horse is basically anatomically correct, but it’s a fantasy horse, a creature of the fabled past, more imagination than reality.

Cavaliere d’Arpino, Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, 1594-95, oil on panel. (DETAIL)

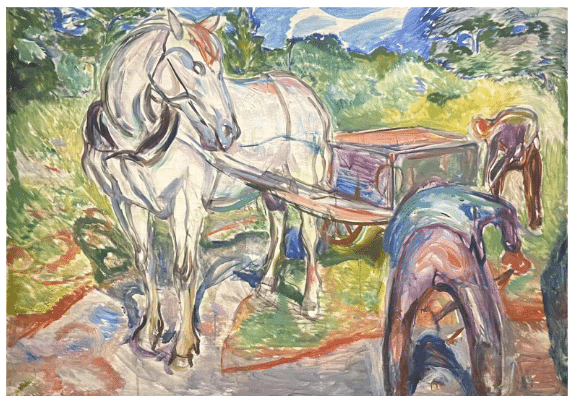

When Edvard Munch took a horse for his subject in 1920, artists no longer had as much to prove as they did in Degas’ day. Munch felt free to paint his workhorse as a shining white beast using wild color and big, expressive brushstrokes to convey the vibrant forces he saw in nature. Dominating the scene amid his salt-of-the-earth workers, Munch’s workhorse becomes almost a symbol of the blunt, robust vitality of life itself.

Edvard Munch, Digging Men with Horse and Cart, oil, 1920.

If you love horses, you might be interested in equestrian portraiture… Johanne Mangi teaches it in her video the Fine Art of Painting Horse Portraits.

Bringing Pastels to Life

Tom Bailey brings his landscapes to life with undulating tonalities and visible mark-making

Artist Tom Bailey is among multiple artist instructors participating in Pastel Live this week. Tom uses energetic and lyrical mark-making in his Impressionist landscapes, showing participants how to create a harmonious fusion by combining patches of bold colors interwoven with subtle tones, lines, and jots on multiple layers.

Pastel Live (August 17-19) is an online event bringing together top artists and teachers for three days of instruction, demonstrations, exploration, inspiration and everything and anything to do with pastels. Find out more here.