“The objection to fairy stories is that they tell children there are dragons. But children have always known there are dragons. Fairy stories are more than true, for they tell children that dragons can be killed.” ~ Terry Pratchett paraphrasing GK Chesterton

It’s important to find inspiration, motivation, and courage wherever you can. If you follow the above quote to its logical conclusion, it goes something like this: art and literature are “more than true” because they can affect us more deeply than many facts or figures.

The original quote (from GK Chesterton, an old world, rather out of fashion writer)

continues: “The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.”

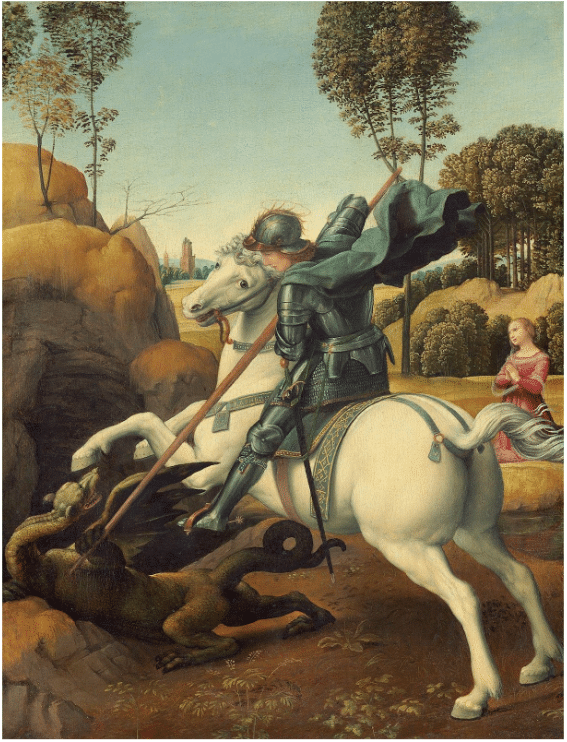

Raphael, Saint George and the Dragon, oil on wood, 1505 about 31 cm × 27 cm (12 in × 11 in)

As a colorful legend, Saint George and the Dragon first appears in Medieval and Renaissance art. The story goes that the dragon was extorting tribute from villagers. When they ran out of livestock and trinkets for the dragon, they started offering human sacrifices once a year. This was evidently more or less acceptable until a princess was chosen as the next offering. A line had been crossed, it would seem, and the saint got involved, rescued the princess, and killed the dragon.

Such imaginative and symbolic forms, Chesterton suggests, are “more than true” because they remind us, on an unconscious level, that our seemingly limitless troubles and terrors are not invincible.

The classic “dragon-fight” motif occurs throughout Western art, from pre-Christian times to Game of Thrones. Specifically, literal readings of “St. George and the Dragon” say St George was a celebrated soldier and saint of chivalry throughout medieval Europe, and the symbolism represents the Christian Church’s battle against evil, heresy, and sin.

Through their combination of psychology and the imagination, symbols and powerful images can have as profound an effect on life as much of what passes for reality on a daily basis.

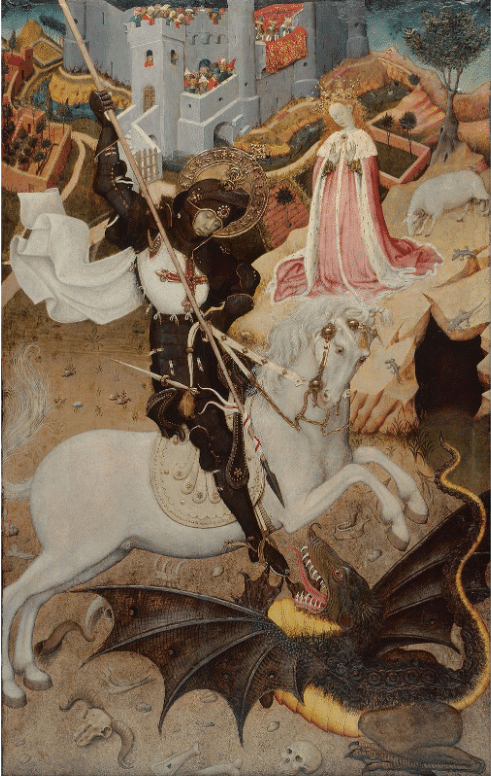

Bernat Martorell, Saint George Killing the Dragon (1435).

In other words, the stories that we tell ourselves about the world and about our place in it are the stuff our truths are made of.

The dragons in the “Saint George” motif tend to on the small side compared to what we’ve come to expect from more recent portrayals of giant fire-breathing lizards. They were no less dreaded or deadly though; like the original sphinx, they’d easily dispatch every adversary until someone special jumped into the ring.

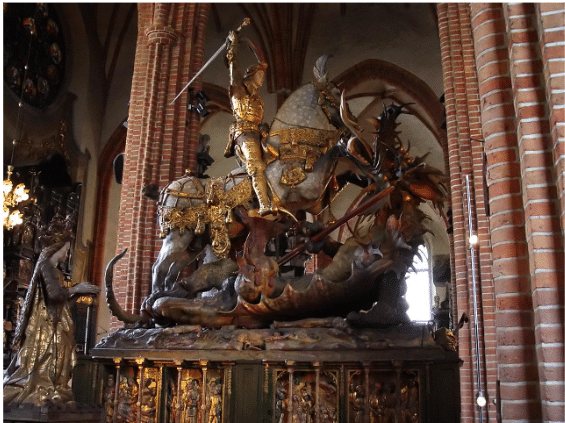

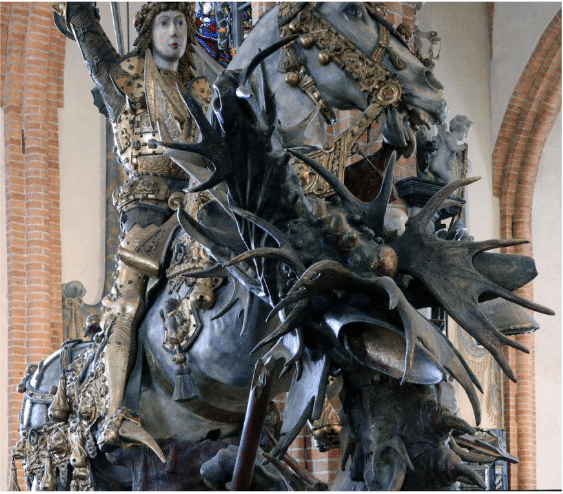

The classic motif is mostly combined to paintings and etchings, but when it’s done as an over life size sculpture made of handcarved oak adorned with real gem-studded bronze and gold – the effect can be breathtaking. Such a spectacular work is found in St. Nicholas’ church Stockholm, Sweden.

Bernt Notke, Saint George and the Dragon, wood carving in Stockholm, 1470s

In this late Medieval work, an armored St. George tramples headlong over the body of the snarling monster, broadsword raised to smite the beast and save the princess. It’s attributed to artist Bernt Notke under commission to the Swedish regent Sten Sture the Elder. It was inaugurated in 1489.

The commission was partly supposed to reinforce the might of the city and its leadership, which was under threat from powerful neighbors. The dragon’s horns are real elk antlers. The figure of George is detachable so it can be paraded through the streets in victory parades. It’s seven feet six inches high, and the entire group is nearly 11 feet long — roughly the size of an average male African elephant.

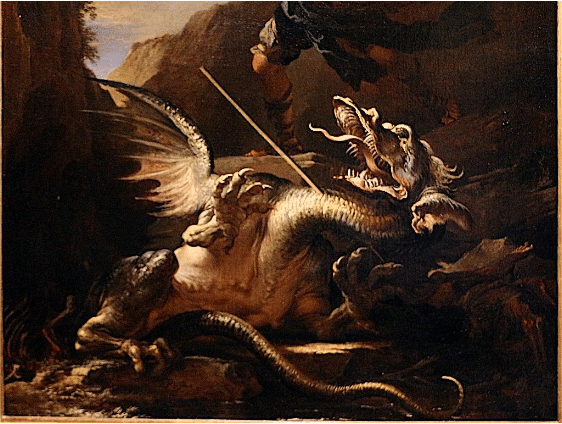

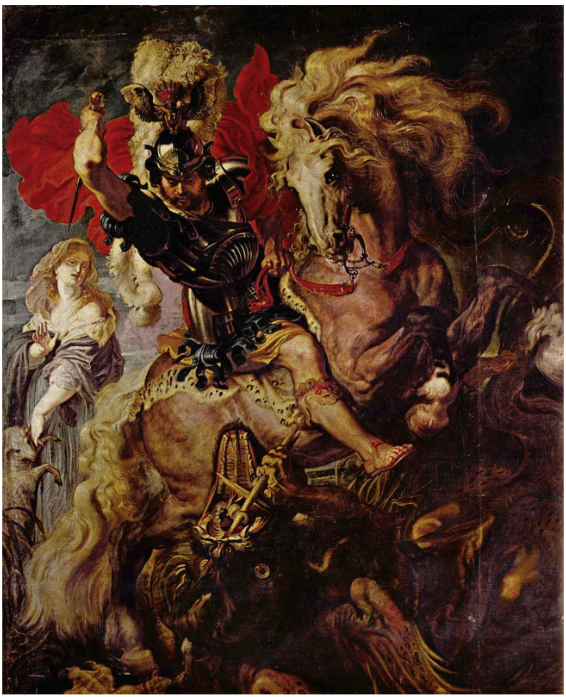

Returning to painting, Flemish Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens treated the subject with characteristic bravado and riotous flair. Saint George and the Dragon made the perfect subject for one of Rubens’s many highly charged compositions referencing classical and Christian history. In Rubens’ elaborate vision, it appears the Saint has already lanced the dragon through its open jaws and is taking aim to finish the job with his sword.

Peter Paul Rubens , ‘St. George and the Dragon’, 1606

With the dawn of the Industrial Age, twentieth century science and technology displaced romantic notions of the arts, banishing stories of dragons into the realm of mythology and children’s stories. There they remained no less true, but most adults lost the ability to access them.

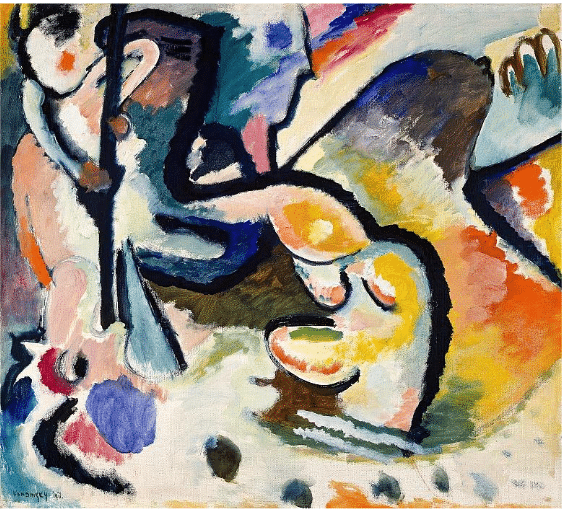

Wassily Kandinsky, Saint George vs. Dragon, 1911

During Modernism the motif all but disappeared into the nebulous realm of abstraction, only to re-emerge via psychology, particularly Jung’s and Joseph Campbell’s, and visually in the Golden Age of fantasy illustration. There, in a sense, fairytales, mythology and symbolism came to a new maturity. Scholars and Jungian psychologists still see them as keys to unconscious foundations within individual minds and the culture at large.

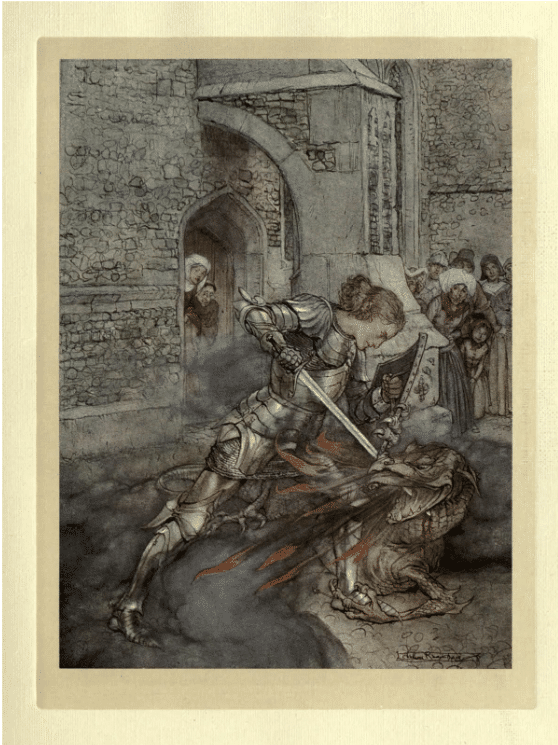

Arthur Rackham, ‘St. George and the Dragon,’ book illustration

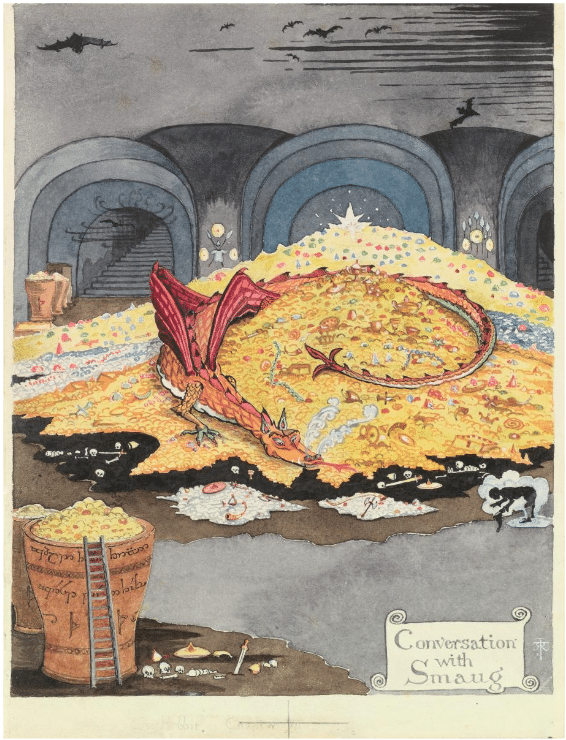

Most recently, the dragon has re-entered into the popular consciousness in a way not seen since the Middle Ages. All manner of sources, from Harry Potter to The Hobbit, have adopted the dragon as a go-to monster to inspire awe and magic – and to show us once more that such monsters are “more than true” because they teach us dark and fearful things can be beaten and overcome.

And that, as Chesterton reminds us, “there is something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear.”

“For we are the music makers and we are the dreamers of dreams,” as Shakespeare said. It doesn’t matter if the stuff of fairytales, mythology, religious parables, or magical legends aren’t provably “real” in the ordinary or scientific sense. They have an essential job to do, one with real and important effects and consequences just the same.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Conversation with Smaug, illustration for The Hobbit, published in 1937.

Visual art that “tells a story” affects viewers in a different way than art which doesn’t. Nicolas Coleman’s Storypainting evokes narratives of struggle, fortitude, and resiliency through characters and setting. His paintings are a way to preserve the fading heritage of the American West. His is true magic. Nicholas takes you into each brushstroke and you see how he creates this incredible effect.

Inside Anders Zorn’s Art Studio – His Palette, Techniques, and More

by Art Historian Emma Jansson

From the Foreward

by Johan Cederlund

Director, The Zorn Museum:

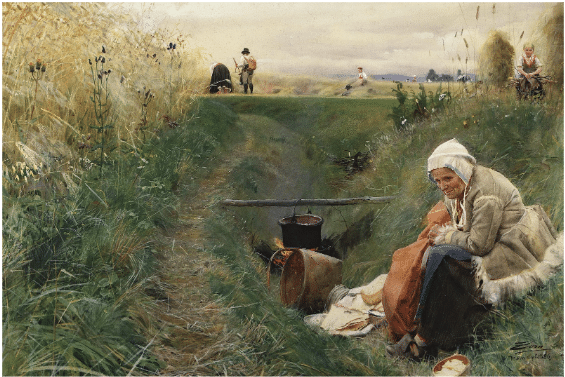

At the turn of the century, Anders Zorn was among Europe’s most celebrated artists. Kings, presidents, financiers, and cultural figures lined up to have their portraits painted by the famous Swede. His sensual pictures of bathing women won wide acclaim, and his etchings commanded prices higher than those of any other artist. Today, Zorn’s name is not as well known, at least not outside of Sweden, but those who encounter his paintings are still fascinated by his brilliant technique, and the ease with which he seemed to create his works. It is as if the paintings were made without effort. Many painters also refer to “Zorn’s palette,” a palette that according to tradition consisted of only four colours: white, yellow, red, and black.

Anders Zorn, “Our Daily Bread (Vårt dagliga bröd),” 1886. Watercolour on paper, 68 x 102 cm. Stockholm Nationalmuseum.

In this book, Zorn’s technique, colours, and work process are for the first time the focus of a scientific investigation. Art historian Emma Jansson refutes the myth of Zorn’s limited palette, and shows how paintings that give the impression of improvisation were in fact preceded by countless sketches and studies, artistic considerations, and deep knowledge of the nature of the materials in use. For Zorn, art was a craft that had to be learned from scratch and in all aspects; he proved himself capable of everything and in any technique.

Anders Zorn, “Herdsmaid (Vallkulla),” 1908, Oil on canvas, 121 x 91.5 cm, Zorn Museum, Mora

Emma Jansson’s research on Zorn was conducted at the Institute for Culture and Aesthetics, Stockholm University. The work resulted in the doctoral dissertation “Making in Context: Reconsidering Anders Zorn’s Oil Painting Practice” (2022), from which this book emerged. It is with our great pleasure that the Zorn Museum, which has followed and supported Emma Jansson in her investigation, is able to contribute to the fascinating results she presents reaching a wider audience.

Interior from Zorn’s art studio in Mora

Get your copy of the book at https://shop.zorn.se.