In 1904, the young, focused, and ambitious Welsh painter Gwen John arrived in Paris. Homeless and living in an abandoned building, she decided she had nothing to lose and knocked on the door of the city’s reigning rock star artist – August Rodin – and suggested she model for him. She found him warm and friendly, and the 63-year-old Rodin (43 years her senior) readily agreed to the arrangement.

As Gwen fell madly in love, Rodin began to see her as his perfect muse. They met in Rodin’s studio early each morning before the assistants arrived. Gwen enjoyed posing, and as the day grew dim, their sessions in the massive candlelit studio stretched into evening.

Gwen John, A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (c.1907–09), oil on canvas.

However, alarmed by her youthful passion, her clinging and constant demand for his attention, Rodin tried to distance himself. After he officially dropped her, she propped up the relationship, writing him daily. She had other lovers, but six years later she was barely taking care of herself. She eventually moved to the suburb of Meudon, where Rodin had a second studio, and where, for a time, she slept in his garden. After her death, the newspaper The Telegraph referred to her as “Rodin’s stalker.”

Luckily for her, shortly before the move, her work found another admirer that would further her career. In 1909, a New York lawyer who had admired her paintings in London offered to buy any of her works that she was willing to sell. Among them were The Convalescent and Girl Reading at a Window, both of which now reside in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

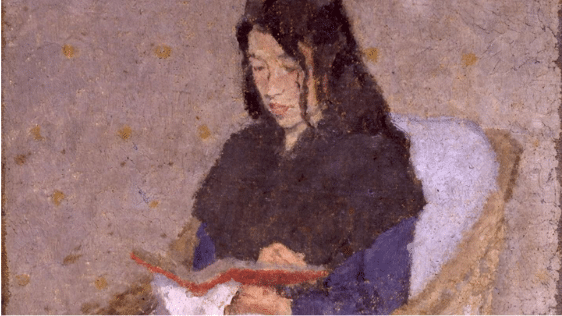

Gwen John,Girl Reading at a Window, 1911. Museum of Modern Art, New York

Influenced by Whistler and probably by Modigliani, Gwen abandoned convention and invented her own mathematical rules for color and tonality. She ditched working in glazes for an original impasto style, applying paint thickened with chalk in shimmering, mosaic-like patches and dabs.

She painted regularly up until the mid-1920’s, even exhibiting multiple times in Paris at the Salon d’Automne. Still, although she continued for a time to send work to galleries and even the Salon, it seems she cared less and less about fame or fortune. Apparently, as if surprised to be asked, she was known rto sell her work for less than a client was offering.

Though she had a long-term relationship with one of her neighbors, she relished her solitude – as when she was a girl walking the cliffs of Wales. When later in life she converted to Roman Catholicism, it was with an intensely personal devotion intertwined with creative work. “My religion and my art, these are my life,” she said.

In Paris she’d known and admired artists such as Paul Cézanne, Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, Matisse, Picasso, and the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, also a close friend of Rodin’s. The early Modern art movement was also partly a religious one, in which the techniques and methods were as important as the subject matter.

Taking her cue from Cézanne, “she extended her painterly practice in a quite risky manner,” art historian Alicia Foster has explained. “She pares down her palette and paints in blocks, leaving brushes of paint that are visible,” The results can be seen in the cool serenity of a work such as The Nun, painted between 1915 and 1921.

Gwen John, A Young Nun, c. 1915-1920

In The Young Nun, the woman is practically encased within her habit, which the artist depicts with a heavy solidity, while the girl’s delicate, sensitively rendered face stares out at us. One senses not serenity but a subdued tension.

Gwen John painted many of the nuns at the convent in Meudon, in whom she sensed the same balance of the spiritual and the earthly to which she’d long aspired.

“A beautiful life is one led, perhaps, in the shadow, but ordered and regular, harmonious. I must stay in solitude to do my work,” she wrote in her notebook.

Gwen John, Mother Poussepin

In these years, Gwen’s work takes on a tremulous quality aided by the thick and nubbly paint mixed with chalk. While a sort of ‘veil’ effect dematerializes the image, the painting also seems like a worn or stony surface into which the image has been imprinted.

After her American patron died in 1924 her work trailed off and she struggled financially (even though a dealer in Paris had told her she could “name her price” for her pictures). In 1926, she moved into a shack built on a piece of wasteland and lived like a hermit with her beloved cats. It was perhaps these later reclusive years, combined with her reluctance to exhibit or sell very much work in her lifetime, that ensured that after her death she would largely be forgotten. By 1933 she’d stopped painting entirely and took to gardening instead.

In September 1939, as war descended on Europe, she wrote her will and travelled without any luggage to Dieppe, a town she had visited a number of times before. She collapsed in a street there, mostly from hunger. Eight days later, at the age of 63, she died in a hospital and was buried next to fallen soldiers in an unmarked wartime grave.

Her final resting place was only discovered in 2014 by a team making a TV documentary. “The sister of Augustus John whose paintings initially overshadowed hers, she is now regarded by critics as the superior artist,” affirms the BBC.

“A picture,” she once said, “requires … a very long time of a quiet mind.”

The Quiet Life of Paint

From the chalky patina

the brush once shaped in

soundless rounds of ministry

to the unsayable,

strokes searching

gentle or rash, smoldering or

ablaze – falling stars

to outlast a thousand

thousand days

passing unnoticed,

and all that stillness

and the beauty of the world.

-Volpe

Gwen John, Interior, 1924