Many in the art world consider Gerhard Richter the world’s leading painter. If you’re curious about contemporary painting, he’s someone you need to know, not just because of his dazzling technical virtuosity, but for his work’s focus on the very nature of seeing and picture-making.

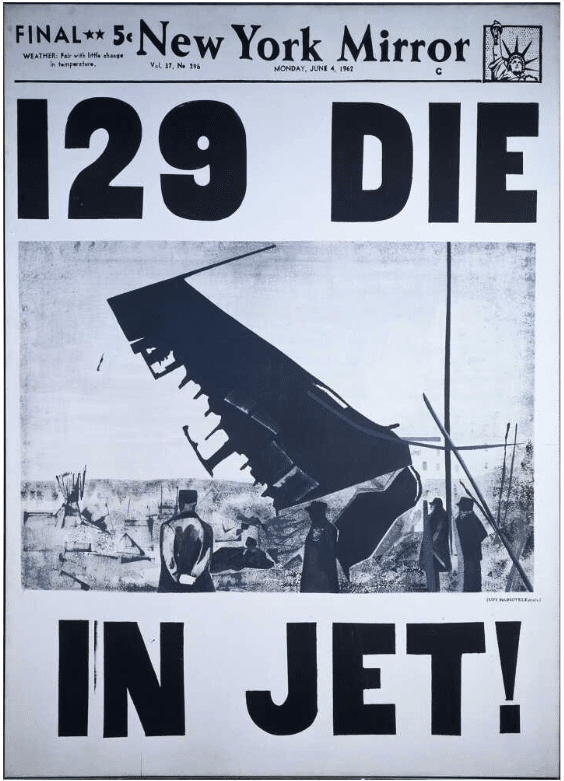

His output at first glance appears confusing – much of it is polarized between, on the one hand, the hyper-realism of paintings that pretend to be enlarged amateur photographs and on the other hand, “random” abstractions created by purely mechanical means, such as, famously, dragging a giant squeegee through the paint. The constant? the work appears to circumvent the hand of the artist. It’s part of his development during the height of Pop Art, where artists like Andy Warhol (below) employed assistants to make multiple silkscreens of copied photographs.

Andy Warhol, Jet, acrylic and pencil on canvas, 100 x 72 inches (1962)

Andy Warhol, Jet, acrylic and pencil on canvas, 100 x 72 inches (1962)

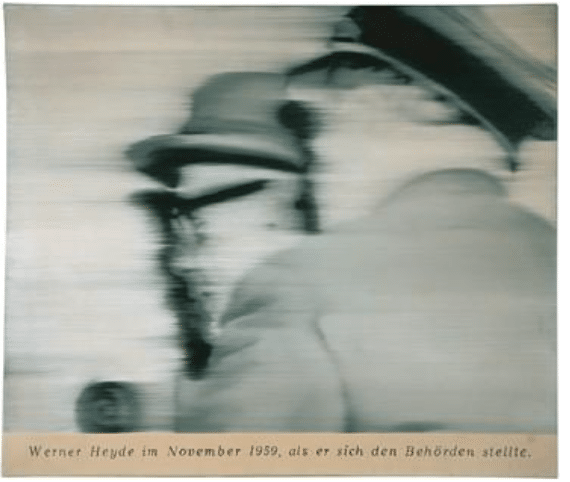

Gerhard Richter, Herr Heyde, oil on canvas, 21 ⅝ × 25 ⅝ inches (1965)

But the reality quite different and at once more comforting and more complex. Richter’s “anti-paintings” still are unmistakably his alone and are, in fact, beautiful contributions to the history of Western art. Despite the act of removal and erasure, the artist, of course, is always and intensely present. Richter’s practice, always in a sense about the nature of painting now (that is, after abstraction, pop, photography, film, and digital), proves painting’s ongoing relevance even as choruses of art world authorities proclaim that painting is dead.

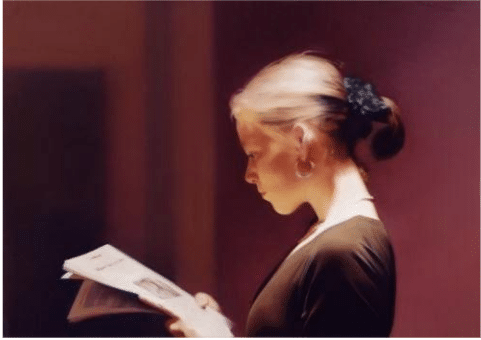

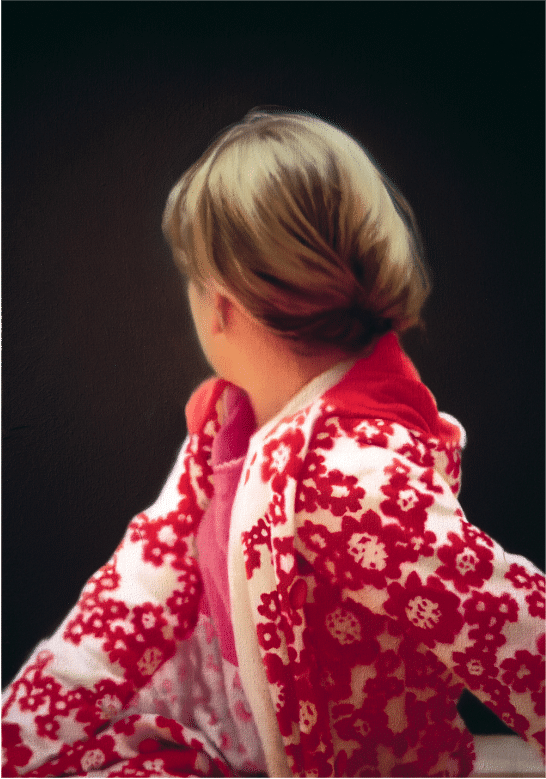

Gerhard Richter, Lesende (Reader), 1994

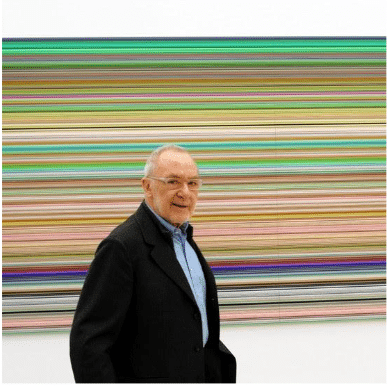

As it has many times over his long (60+ year) career, Richter’s work has morphed again into two totally disparate modes: this time, apparently chance-induced paint pouring on one hand and cold, algorithmic digital manipulation based on one of his paintings on the other (for example, see the “Strip” painting below).

Gerhard Richter, one of the new poured works

Richter says, “Hope and belief are…unique to humans. Animals don’t go around hoping. [Religion] slowly broke down over time. Perhaps starting right before Nietzsche. And nowadays there aren’t many believers. But there’s an unbroken urge to believe—whether in Prada, or some other brand of clothing, or in anything…. “

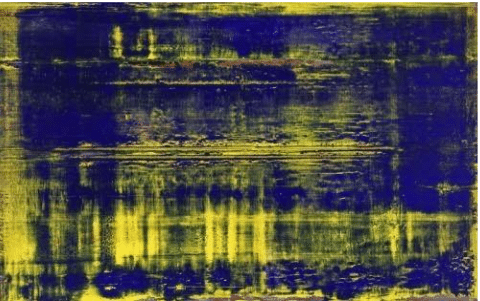

Gerhard Richter, Abstract Painting

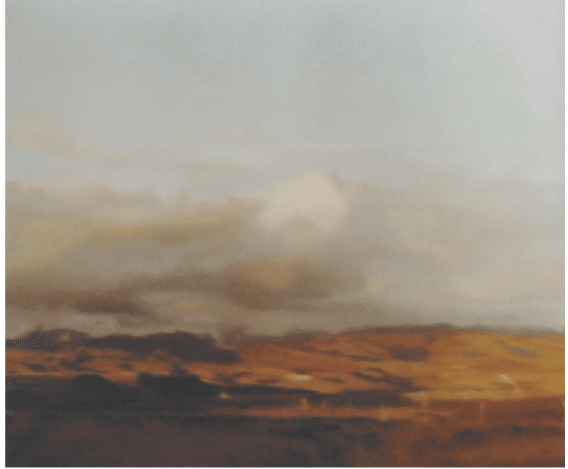

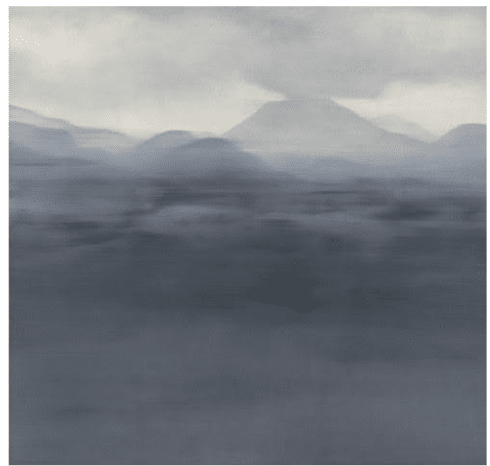

Richter’s atmospheric “landscapes” – which he began painting in the early 1970s – could inspire legions of tonalists and abstract landscapists for years to come. But taking Richter at face value is to miss what’s most historically relevant about his art. Richter isn’t painting landscapes; he’s painting poorly taken photos of landscapes, often making subtle, “anti-painting” moves like splicing a sky from one photograph into the landscape scenery from another.

Meanwhile, just like his supposed realism, his “abstract pictures do indeed show something, they just show things that don’t exist. But they still follow the same requirements as figurative works: they need a setup, structure. You need to be able to look at it and say, “It’s almost something.” But it’s actually representing nothing. It pulls feelings out of you, even as it’s showing you a scene that technically isn’t there.” -Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter, Betty, 1988, oil on canvas, 102 × 72 cm. Courtesy: Saint Louis Art Museum

Gerhard Richter, Abstrakt Bild (1980)

Richter, spry at 82, in front of one of his new “Strips” works.

It’s all a glorious, dizzying conundrum. Abstract painting, if not all painting, is “a secular pilgrimage toward universality,” as a recent WSJ article on Richter put it: “Most of the Ab-Exers shared an impulse to bring the hope of the world into their art.” Not Richter. Richter wanted to close the gap between Duchamp and painting, to make objects out of signs without definite referents, confronting us with the inexplicable beauty of our bewildering and often horrific modern lives.

September, Gerhard Richter

The paintings that result from Richter’s sometimes chaotic, sometimes exacting, and always time-consuming processes used to make his paintings seem to mirror the vulnerability, striving, and patient questioning he sees as the essence of humanity.

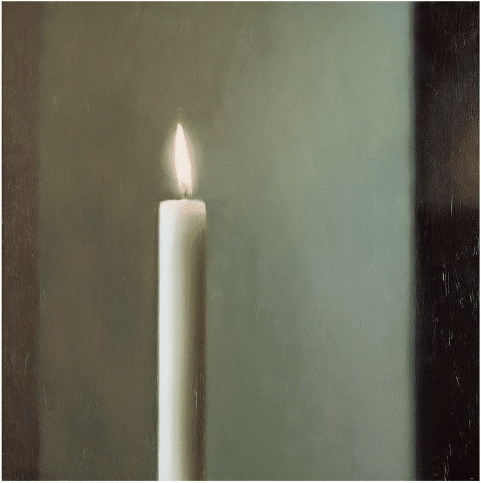

All of Richter’s diverse works spring from the same artistic project, namely his “belief in painting’s necessity born of radical doubt in its potential …. a credere quia absurdam’ (from St. Aquina’s phrase ‘I believe because it is absurd.’)” Despite his refusal of sentimentality in any form, for Richter art and beauty are humanity’s saving graces in the face of often hard-to-bear reality.

As he has said many times, if our better selves are to survive, “we need beauty in all its variations.”

Onward and upward.

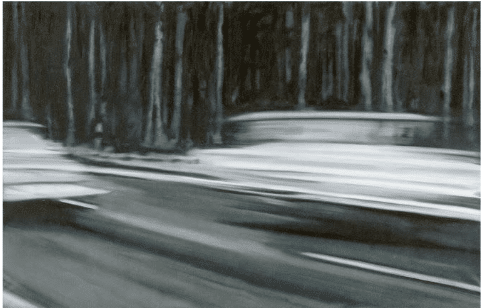

Gerhard Richter, Two Fiats (speeding cars)

Gerhard Richter, Kerze (Candle), 1982

If you’re ready to dig deeper into your work for your own authentic voice, check out Steve Curry’s video, Finding Your Voice: Painting with Creative Expression.