More people have heard of Winslow Homer than of Homer Dodge Martin. And though he’s not a “household name” (show me a 19th century American painter is?!), Homer Dodge Martin interests art historian as one of the more versatile and “poetic” of the famed “Hudson River” landscapists of the 1820s -‘80s. Some see him as underappreciated and ripe for a retrospective.

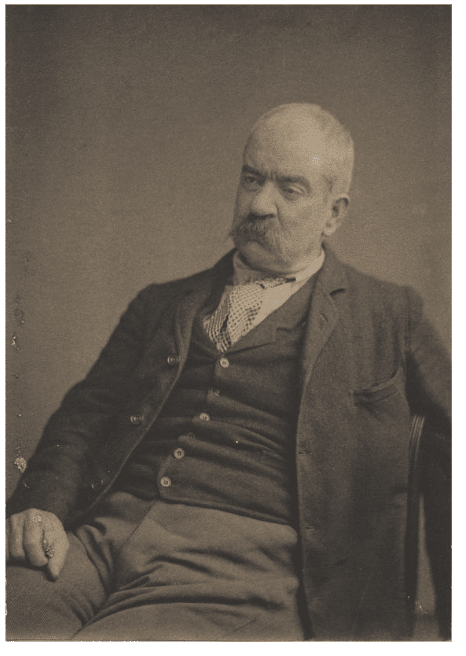

Homer Dodge Martin

Homer D. was always the odd man out, always out of step the square peg who never fit in, and more often than not, he shot himself in the foot when it came to his career. Self-taught, he did most of his best work after he’d started going blind (1880s).

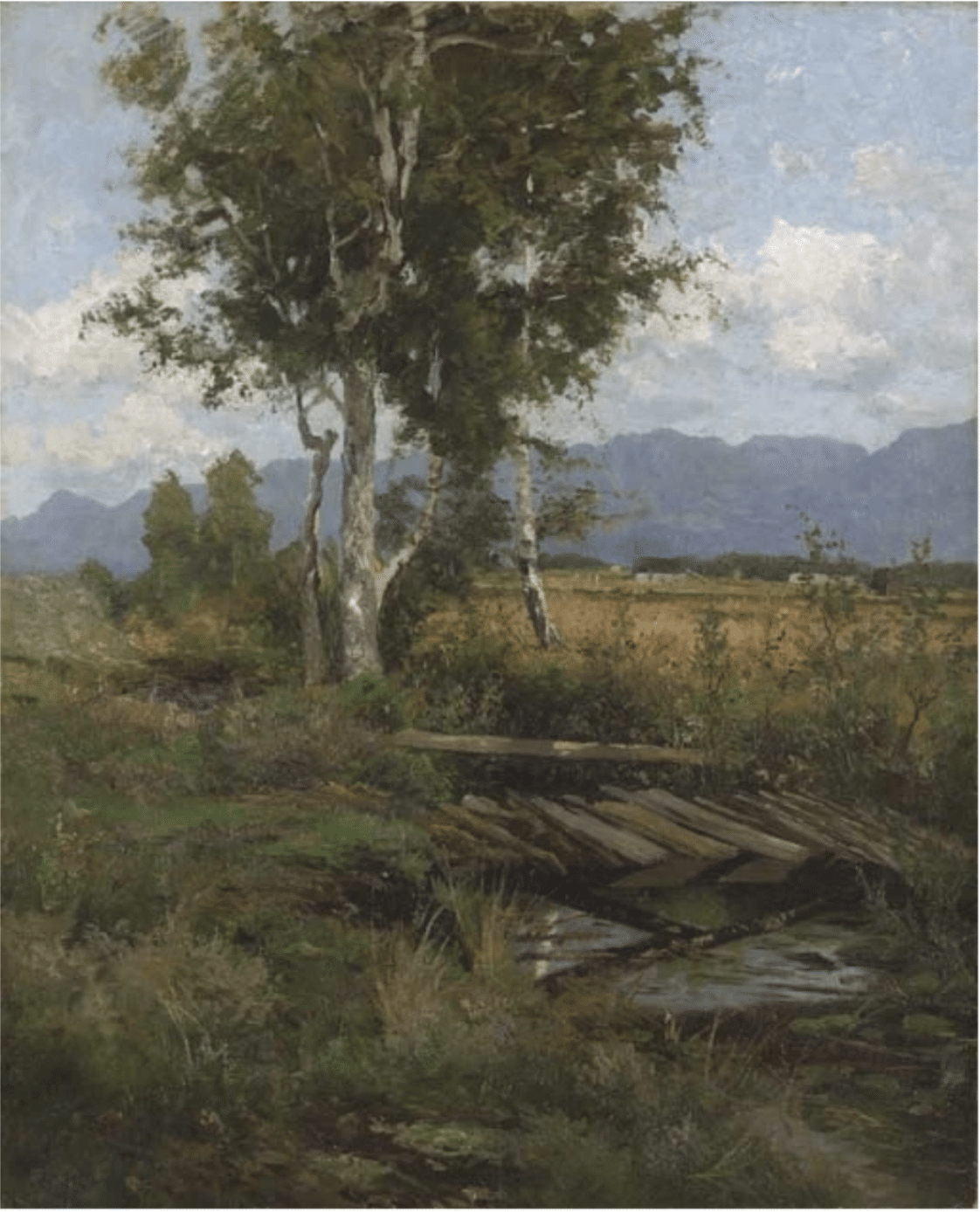

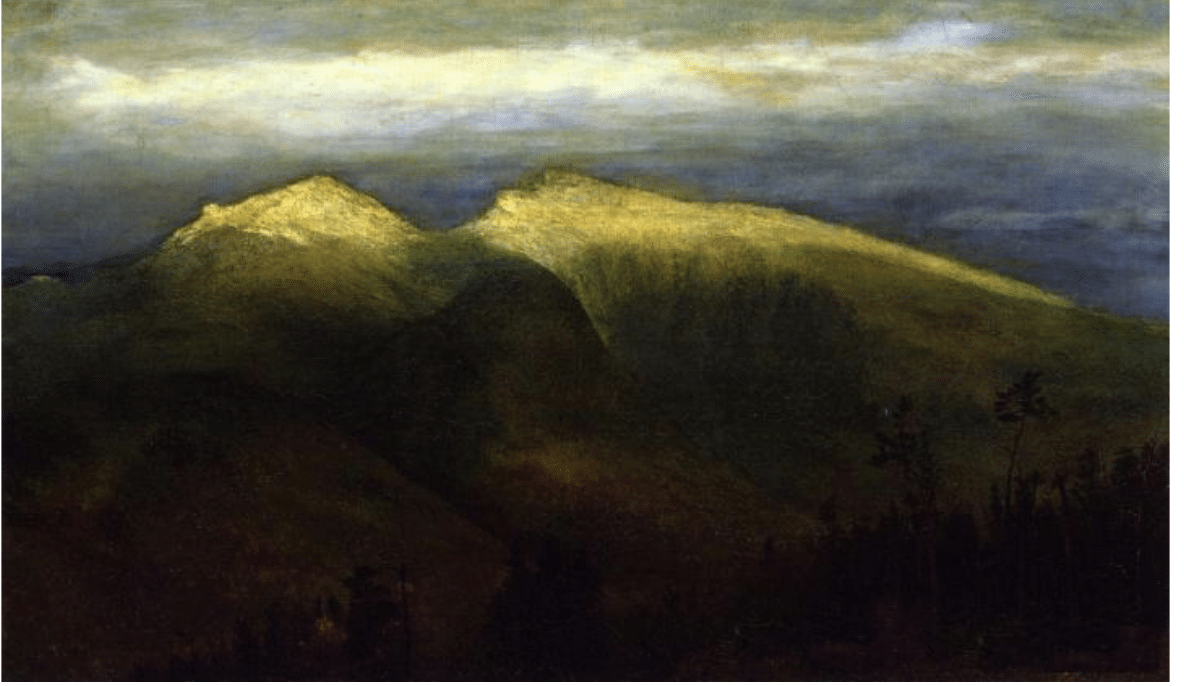

Homer Dodge Martin, Toward the Adirondacks, c. 1890

Early on, he gave up the standard outdoor sketching excursions (1860s), preferring good food and plenty of beer and brandy, a comfortable chair and a cigar to climbing mountains on horseback.

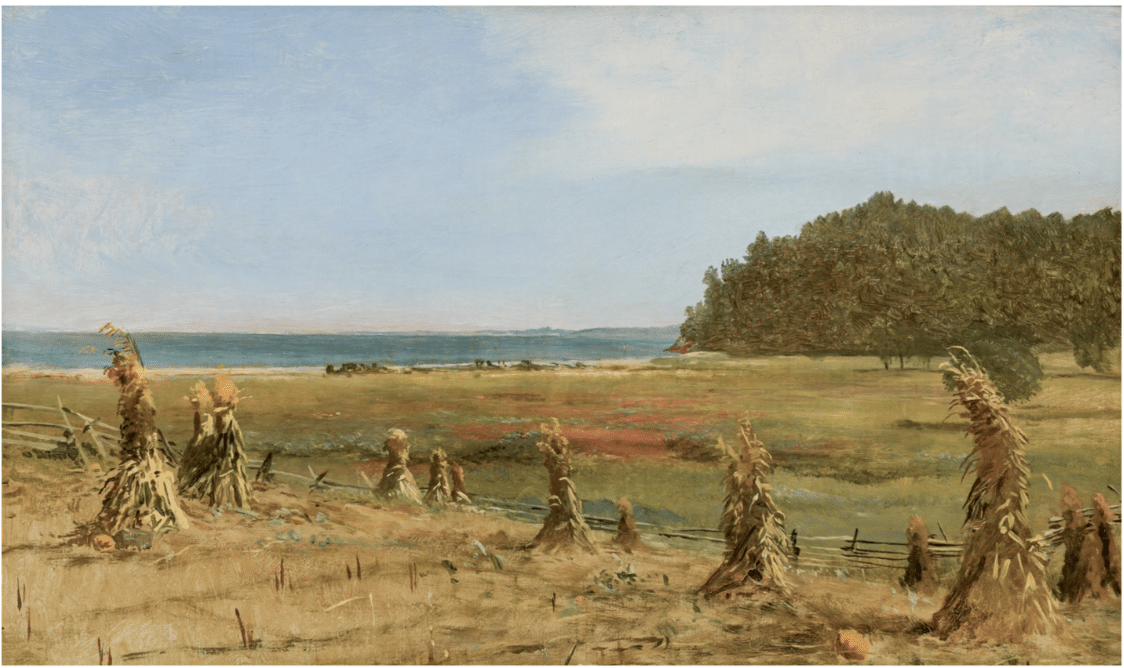

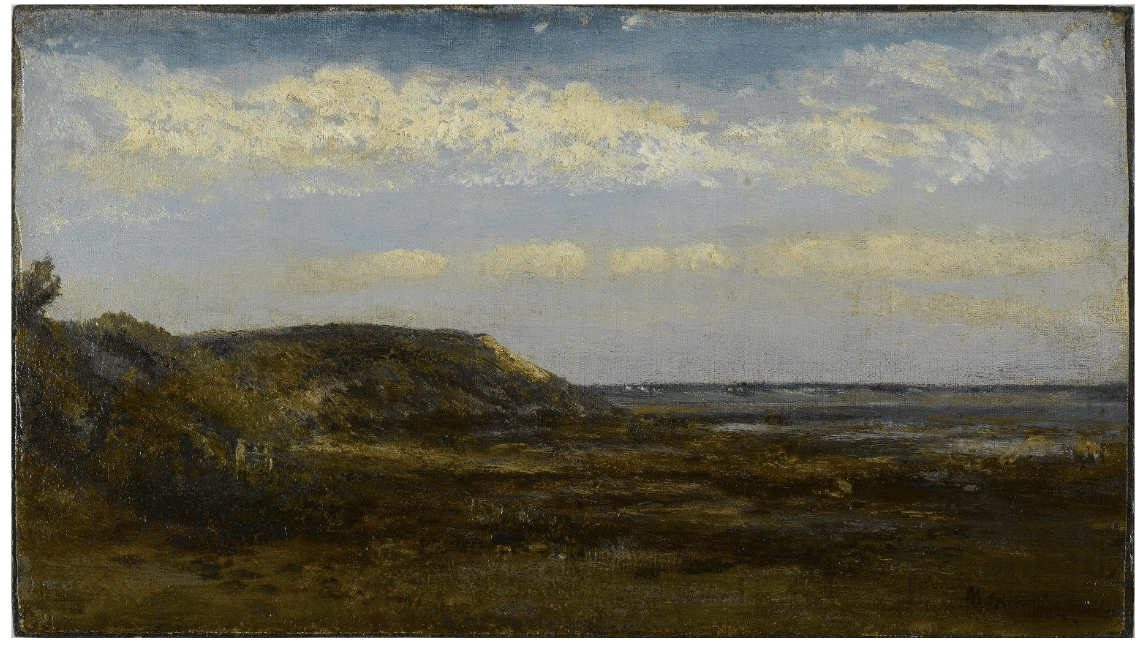

Homer Dodge Martin, Hudson River Landscape, c. 1860-1865 – his earlier, Hudson River style.

But by the time people really got interested in him (during the 1870s), he’d changed his style, abandoning what the public had started to like in his work: During a trip to Europe he was captivated by the Barbizon school and the Impressionists, and thereafter his painting style gradually became darker, moodier, and more loosely brushed.

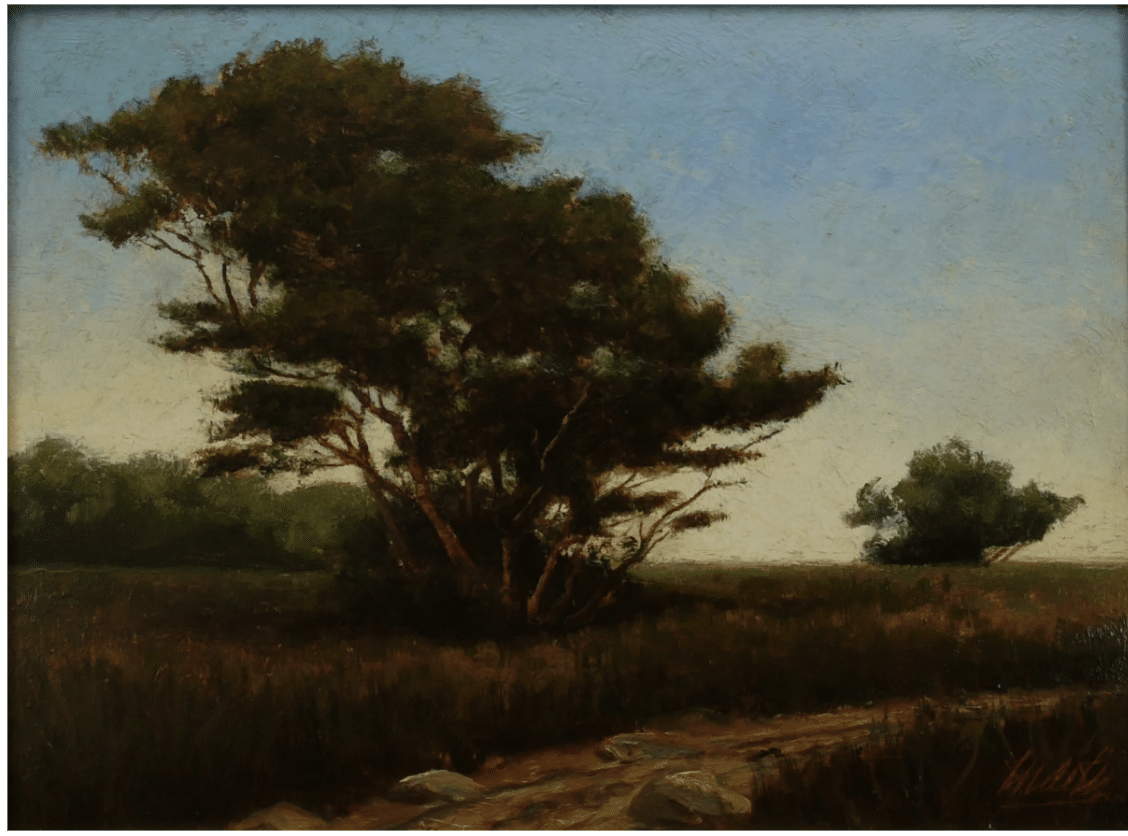

Homer Dodge Martin, Trees in a Field, 9” x 12,” 1875

And at a time when patrons expected the artists’ presence at viewings, he ghosted, habitually neither in good health nor adept with the social graces. It didn’t help his career that 1. He moved to France where he lived between 1882 and 1886 and 2. he had a reputation as a bit of an oddball who preferred long stretches of “soaking up” between bouts of actually doing any painting. (One cartoon captioned “Homer Martin Hard at Work” showed him out with several other painters hunched over their easels while he snoozed beneath a tree.)

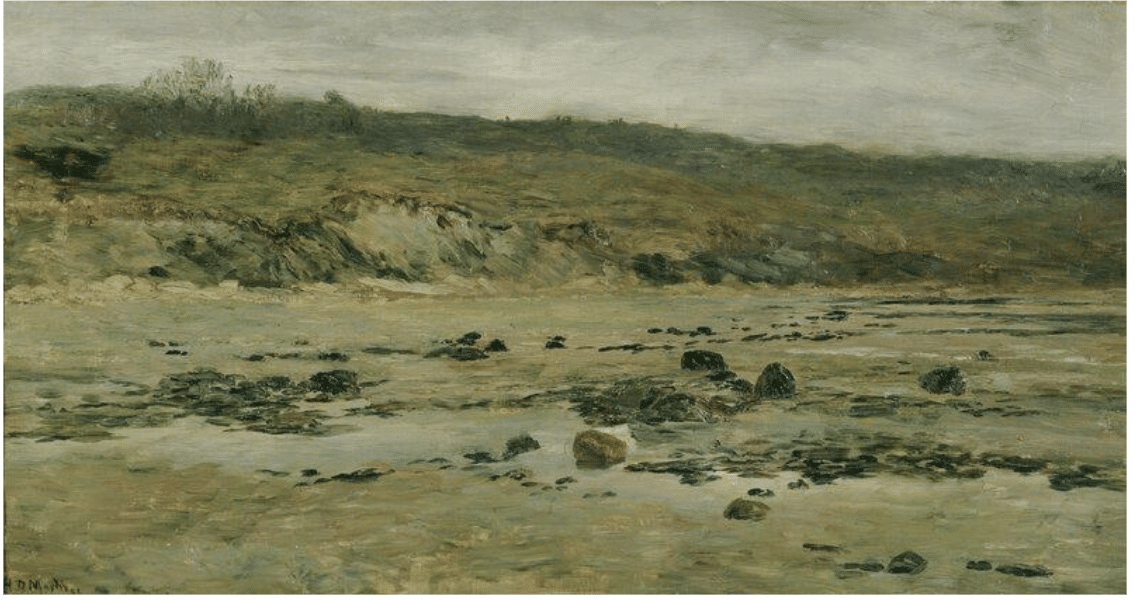

Homer Dodge Martin, Normandy Coast, 1884. Oil on board, 7 3/16 x 12 11/16 in. (18.3 x 32.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Charles A. Schieren, 15.281 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 15.281_PS2.jpg

He was perpetually penniless and in debt. Nonetheless, he was a member of the artistic in-crowd; he was a member of the National Academy and a member of the Century Club, both prestigious artists institutions in New York, and he was represented by among the best galleries of the period.

Homer Dodge Martin, Normandy Shore, 1884, Oil on canvas, 12 × 24 inches

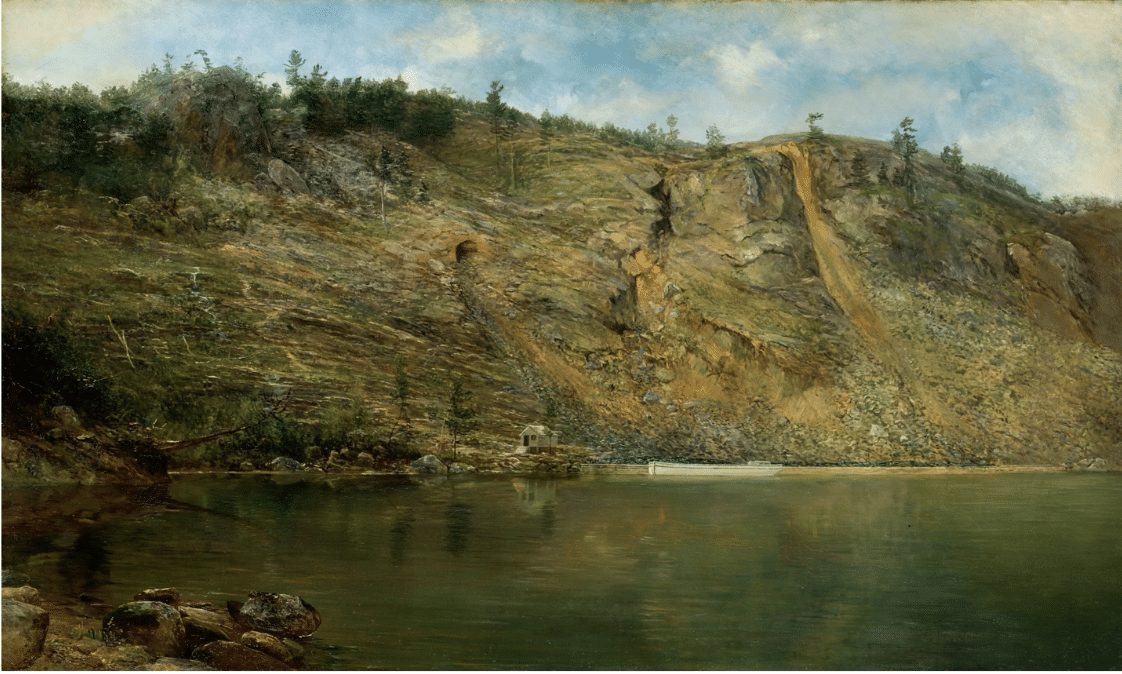

His best paintings defy the prevailing conventions of his day. Martin painted The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York, (below) in a sharp, realist style more reminiscent of the 20th century sensibility of George Bellows than any of the Hudson River School types of the time.

Homer Dodge Martin, The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York, ca. 1862, oil on canvas mounted on fiberboard, 30 1⁄8 x 50 in. (76.5 x 127.0 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of William T. Evans, 1910.9.11

Earlier artists had pictured America’s scenic mountain peaks and virgin forests. Not so here. From a mineshaft that (as the Smithsonian Museum says) resembles a bleeding wound, iron ore traces and rubble stream down the side of a cliff to the water, where the ore was loaded onto barges. The Bay State Iron Mine Company ran blast furnaces that supplied the steel for America’s railroads.

Painted during the Civil War, Martin’s canvas “quietly asserts the primacy of the North, whose strength lay in its natural resources and manufacturing vs. the agrarian ways of the South,” says the Smithsonian. So, you could say Martin’s mine literally oozes industry, foreshadowing the overwhelming wave of economic development that not only determined the outcome of the war, but also strongly influenced the development of the reunited country throughout the industrializing decades of the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

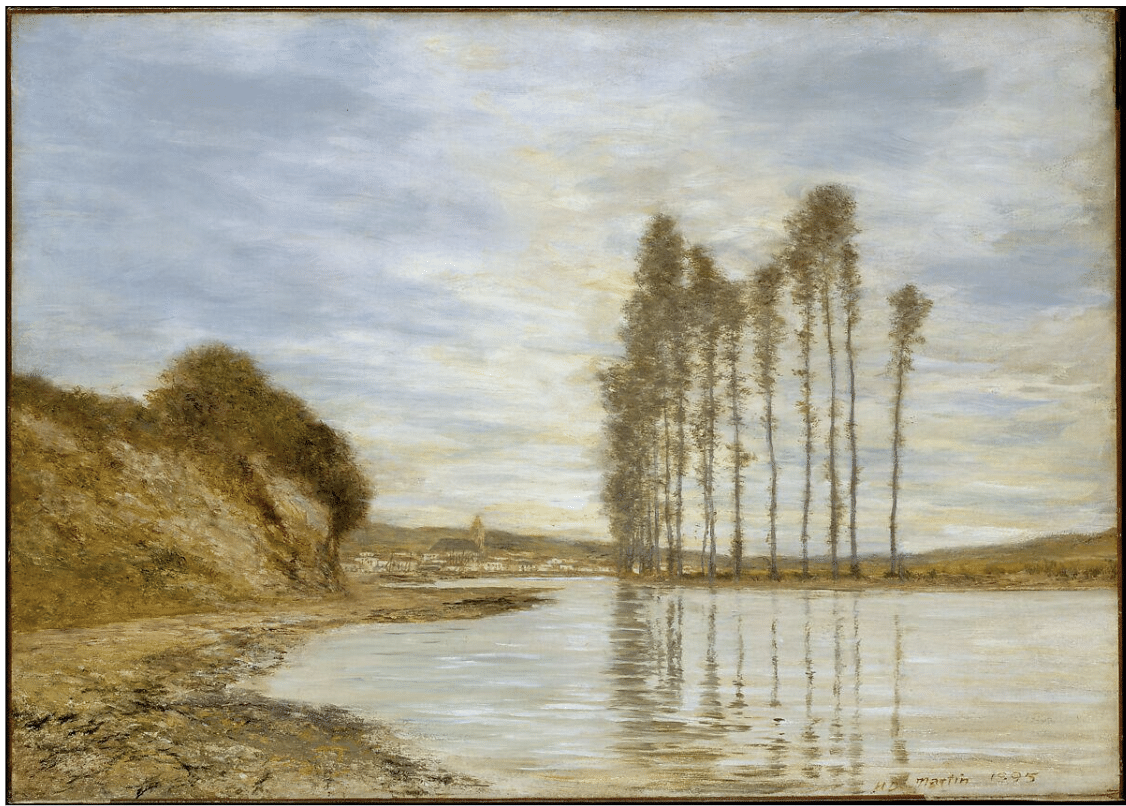

Martin’s dreamier landscapes, painted from memory, are most closely associated with the Barbizon School. The story of his most well-known work, The Harp of the Winds (1895), says a lot about his life.

Homer Dodge Martin, View on the Seine (Harp of the Winds), oil, 1893-95, 28 3/4 x 40 3/4 in. (73 x 103.5 cm)

When in the late 1890s his New York friends learned he was homeless and living with relatives, destitute and sick with terminal throat cancer, they solicited money through the Academy’s membership. Rather than accept it outright, Martin insisted it be regarded as an advance on the purchase of the “Seine picture” – View of the Seine, famously known as “The Harp of the Winds.” By donating this painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, his friends aimed to save his work from ever being forgotten. The museum to this day attributes the acquisition to the generosity of “Several Gentlemen, 1897.”

Homer Dodge Martin, Mount Washington from Randolph Hill.

The Hudson River Style is alive and well in the paintings of Eric Koeppel. If you’d like to learn the authentic techniques of this phase of American landscape painting check out Eric’s videos, Techniques of the Hudson River School Masters, volume 1 and 2.