You can learn a lot from studying artists who never gave up. Consider the difficult life and late-blooming career of Shiko Munakata.

The young man who would eventually be “Japan’s van Gogh” hadn’t gone to high school. He found himself, in his early 20s, stuck in a dead-end office job. It was better than being covered with grease working on cars and trucks at the family garage. As a “clerk” in an accounting firm, at least the young Shiko Munakata could use his ledger as a sketch pad when the boss wasn’t around.

Born in 1903, he was the third of 15 children raised by a local blacksmith. Shiko grew up in a world far from the glitter and jazz of Modern Art. He was 17 when he saw a still life by van Gogh on the cover of a magazine and told anyone who’d listen that he would someday be as great an artist for Japan. Two years later he arrived in the big city determined to become a professional painter in oils and was summarily rejected by the establishment. So he scrapped for pennies repairing shoes and selling street food, his workdays steeped in the nauseating steam of decomposing soybeans to survive.

Still, he remained as artist through and through. In 1926, Munakata saw black-and-white woodblock prints by an eccentric, self-taught printmaker and plowed himself into the medium for the better part of a decade. In 1935 his work caught the eye of Yanaki Soetsu, the father of mingei, the modern folk-art revival movement in Japan. He’d found his medium and his voice as an artist, and his life changed forever – he had been discovered.

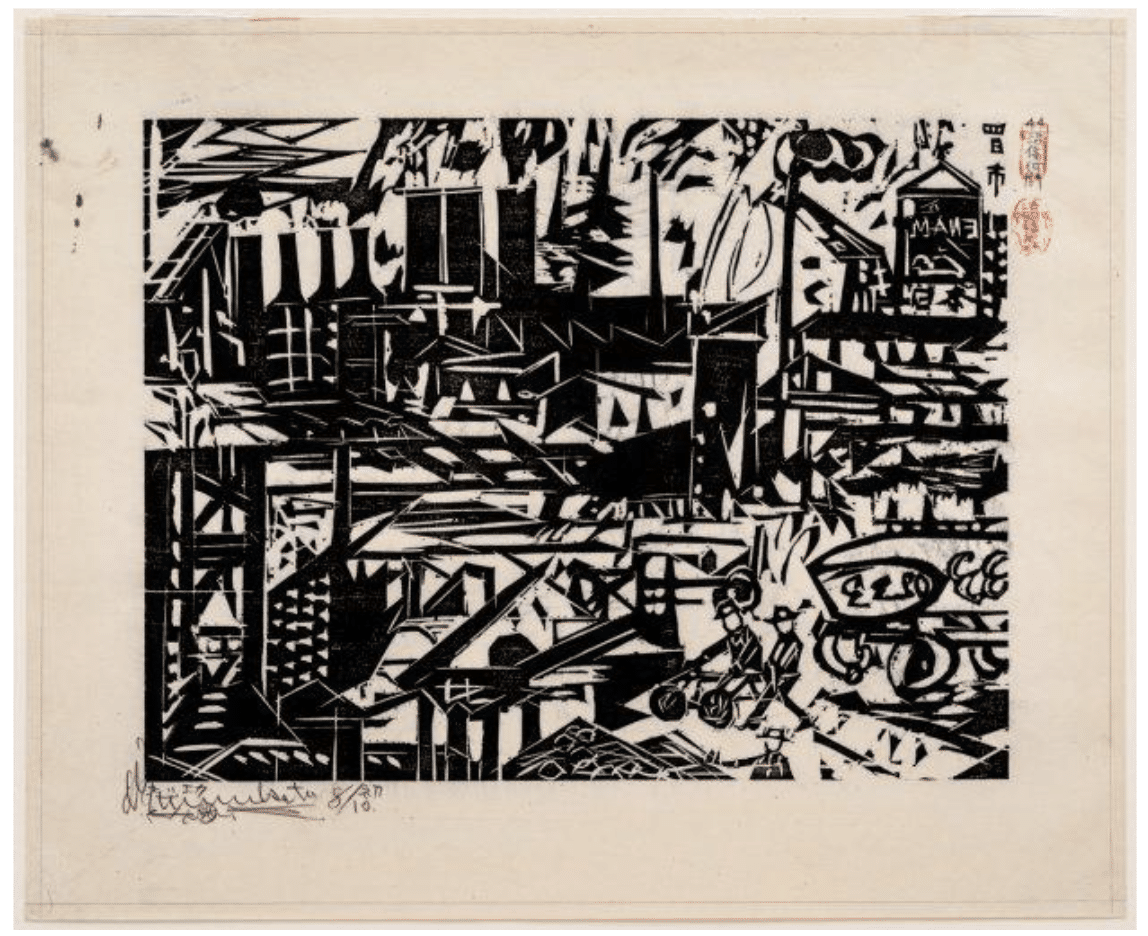

Shikō Munakata, detail of “Mukō-machi: Crossing Point of Highways” from the Tōkaidō Series (1964), photograph by Nicholas Knight (collection of Japan Society, © Shikō Munakata)

From the start, Munakata pushed Japanese ukiyo-e printmaking beyond its traditional roots in Buddhism and the 17th century glory days of the Edo period. Abruptly in 1945, Munakata was forced to leave Tokyo after a violent two-day American firebombing blitz. It was one of the most destructive acts of war in history, on a par with Hiroshima or Nagasaki, and it decimated the city. No one knows how many died, but most estimates put it at 100,000 killed and one million left homeless overnight. Though Minakata was unhurt, his pet was killed, and his house and most of his woodblocks were destroyed. He was evacuated to the mainland city of Toyama with little more than the clothes on his back and the determination to rebuild his studio and career.

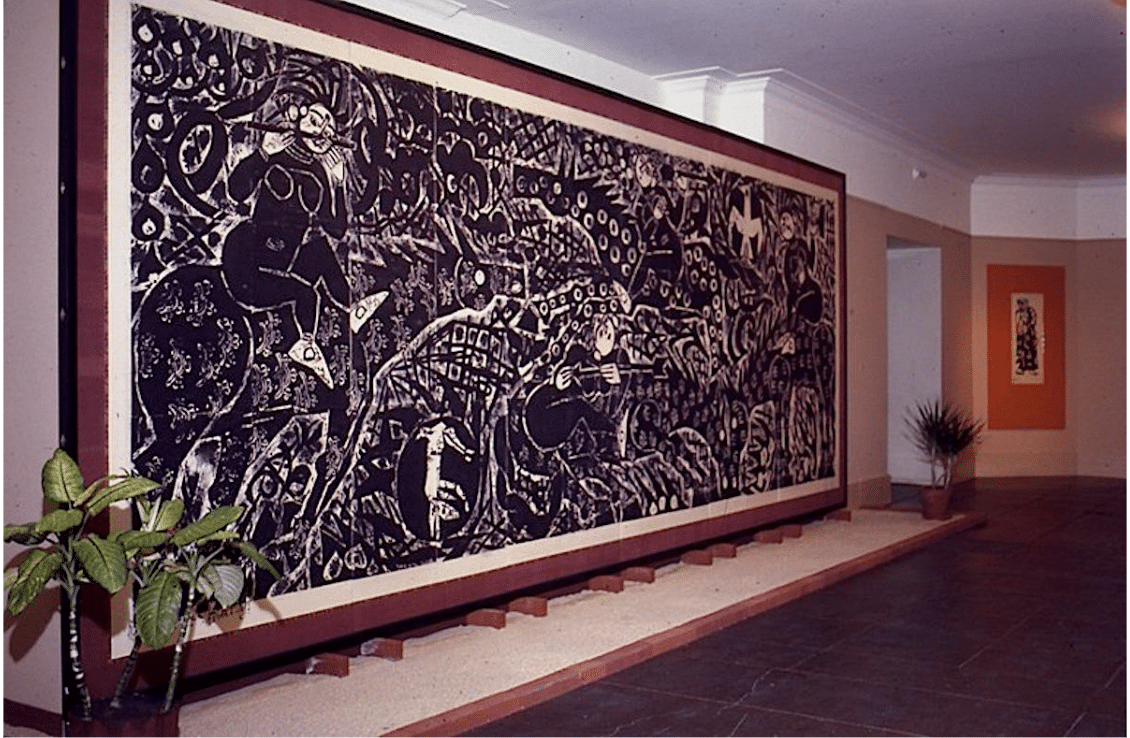

And indeed he did. From his new base in Toyama, Munakata produced highly original woodblock prints, paintings in watercolor and oil, calligraphy, and illustrated books that brought him international recognition. He moved into a bigger studio in Kamakura, Kanagawa prefecture and traveled to the United States and Europe in the 1950s. He swept up major awards in Lugano, Switzerland (1952), São Paulo, Brazil (1955) and at the Venice Biennale in 1956.

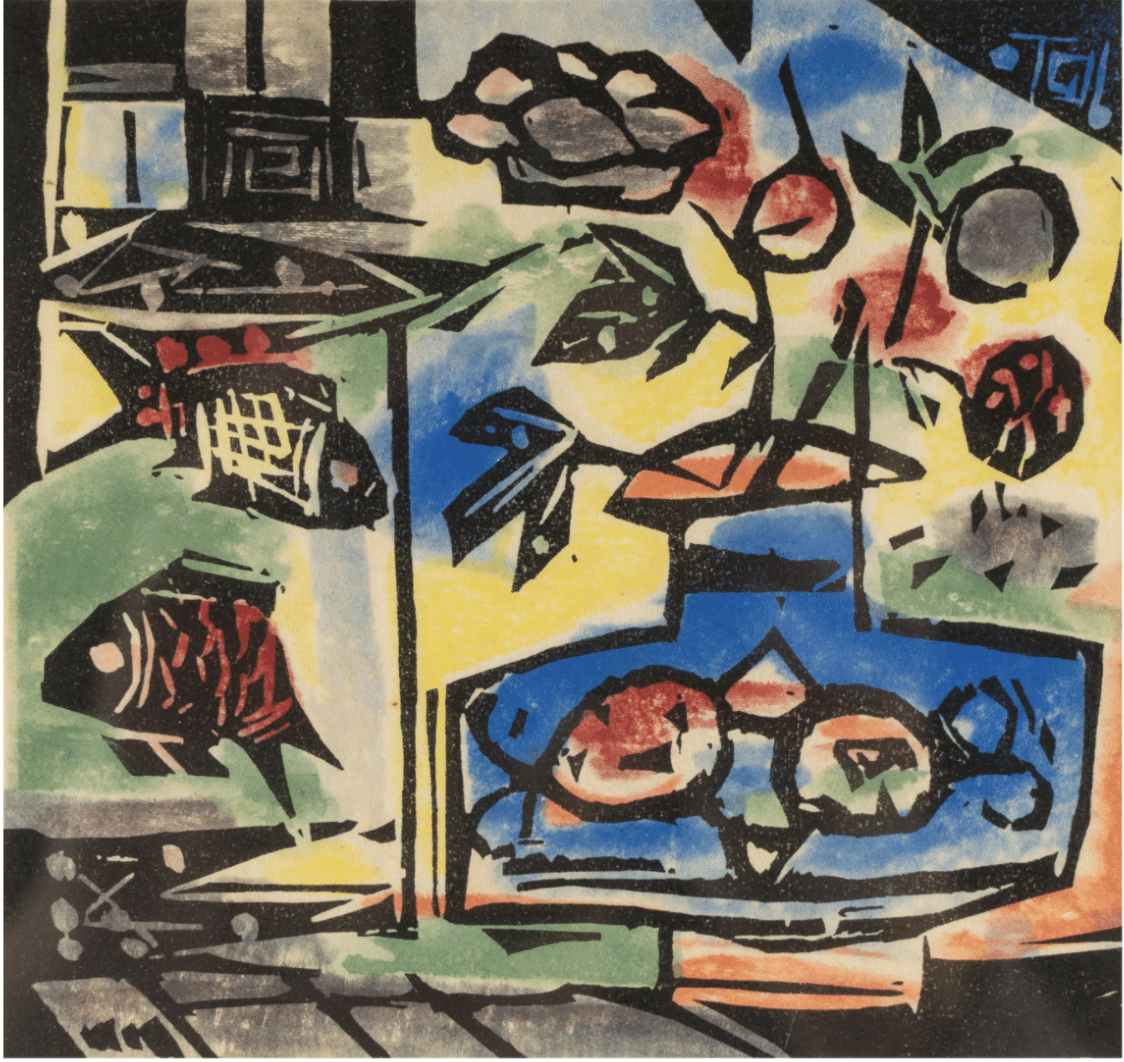

He continued to develop a modern, now Pop-art inflected approach, using bold, spontaneous, and sketch-like lines that revolutionized the woodblock print. If that wasn’t enough, he had a multimedia, anything-goes practice, encompassing printing, painting, bookbinding, illustration, paper arts.

No matter the medium, Munakata’s artistic explorations were characterized by a spirited curiosity and relentless experimentation. He incorporated a vast array of sources and inspiration in his works, including Japanese folk tales, Buddhism, Western literature, poetry, film and television.

Now that he was internationally acclaimed, he was known in his home country as the “world-revered Munakata.” The Japanese government presented him with the Order of Culture in 1970. He died five years later at his home from liver cancer, and the Munakata Shiko Memorial Museum of Art in his hometown Aomori opened its doors for what would have been his 73rd birthday.

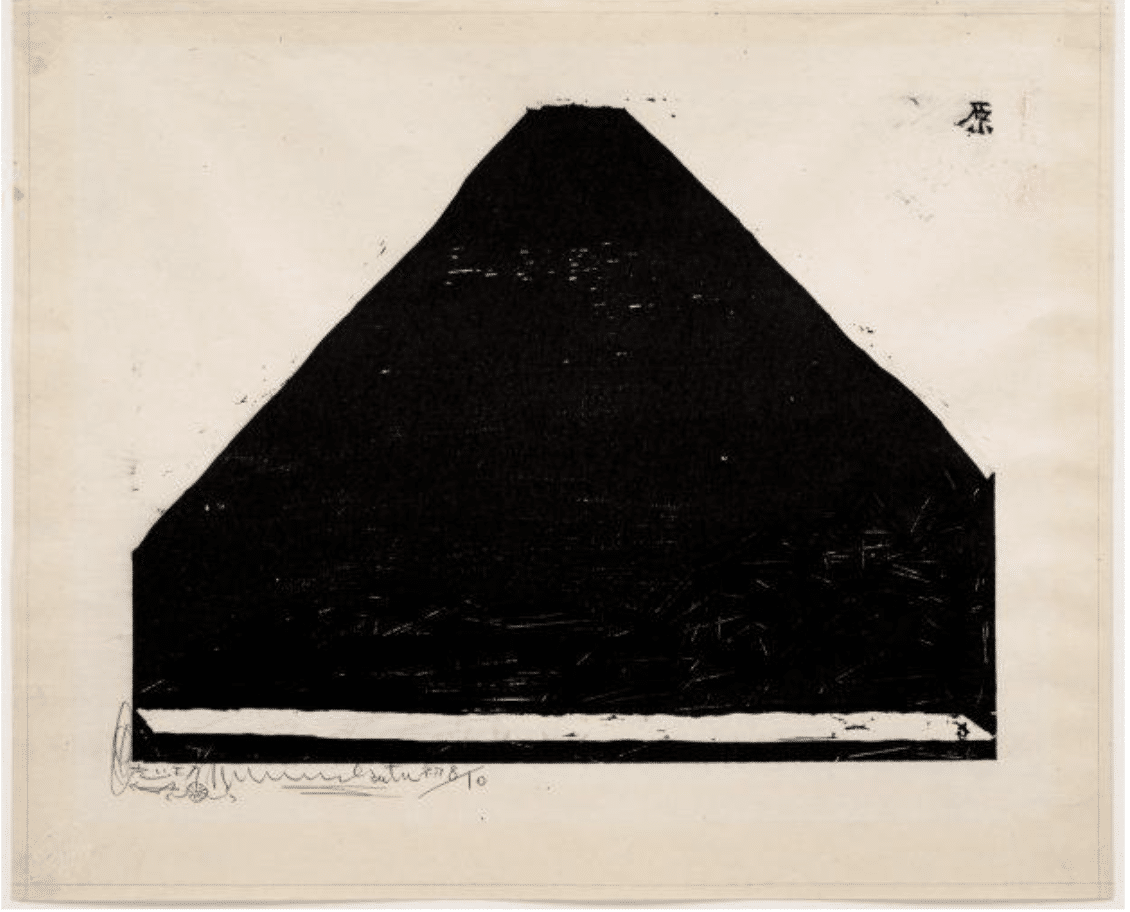

Hara: A line at the Foot of Mount Fuji. Tokaido Road Series. 1964. Woodblock print, black and white sumi ink. 58 x 47 cm.

In 2013, Japan commemorated the 120th anniversary of Munakata Shiko’s birth with a retrospective that toured the three regions that influenced him most: Aomori, his hometown; Tokyo, the center of his brilliant artistic careeer; and Toyama, where he lived after being evacuated. He’s now considered one of the most important Japanese artists of the 20th century.

“The woodcut, unconcerned with good and evil, with ideas, with differences, tells us that it consists of truth alone.” – Shiko Munakata

Shiko Munakata at the Brooklyn Museum in 1968