Sometime in New York City around 2007 several early and mid-career artists gathered around the studio of Chinese American watercolorist Paul Ching-Bor. Ching-Bor is known for dynamic, large-format watercolors of urban scenery. Since going their separate ways, these artists have evangelized and extended Ching-Bor’s innovations in impressive large-format works that push the watercolor genre into new territory.

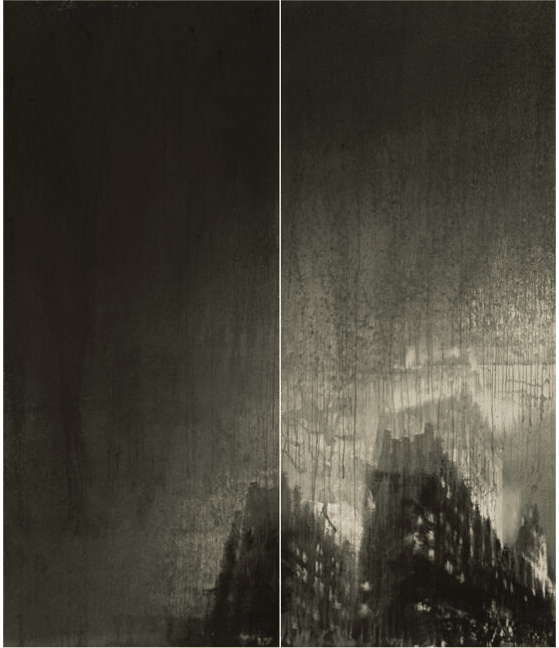

Paul Ching-Bor, UNDER THE SOUTHERN CROSS / THE FAREWELL IN CARRAMAR I, watercolor on paper 32.5” x 51.5”.

The paintings are not abstract, although they lean that way. Tightly rendered realistic details battle across the picture plan with expressive drips and layered washes. Collectors seem drawn not only to the group’s moody urban iconographies but to the way they evoke worldviews that probe the modern psyche.

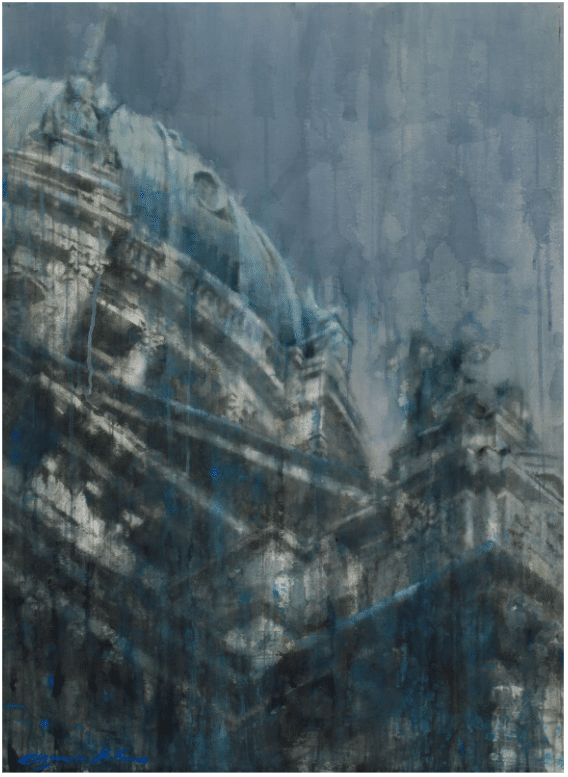

Chizoru Morii Kaplan, The Louvre VI, 46” x 52”

Chizoru Morii Kaplan is one of the artists who came together at Ching-Bor’s studio around 2007. Her previous work as a freelance architectural renderer afforded her the advantage of a very sharp eye and hand for sweeping skylines and intimate architectural details likely to be overlooked by untrained eyes.

Combining architectural specificity and expertise with abstract brushstrokes and atmospheric drift, her work can offer her viewers, she says, “a more truthful depiction” of how it feels to inhabit the cities she paints.

A fellow of the League for study at the Paris American Academy, her paintings have been exhibited in New York City at The National Arts Club Gallery, the Salmagundi Club, the Bertrand Delacroix Gallery, and the Springfield Art Museum in Springfield, MO.

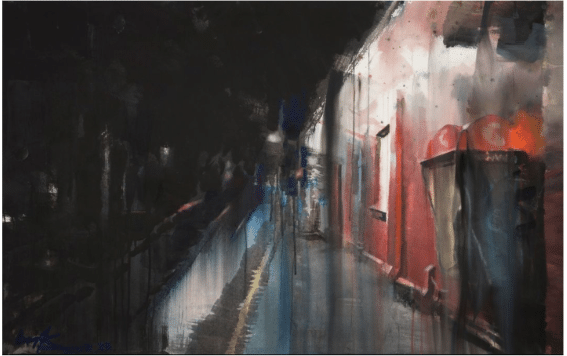

Chizoru Morii Kaplan, Lonesome Journey III, 45” x 65”

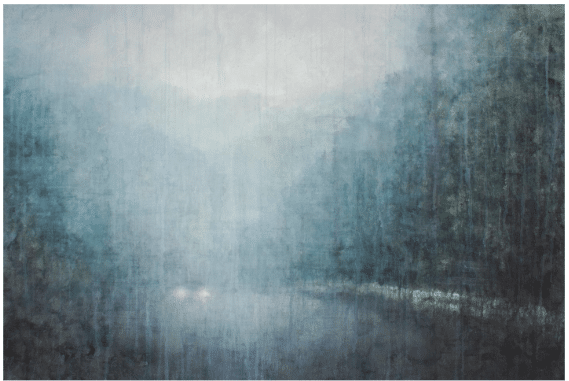

Kathryn Keller Larkins is another artist working with, among other media, large-scale watercolors with a contemporary feel. She also lives and shows her work in New York City.

Kathryn Keller Larkins, Through Security, watercolor on paper, 51” x 81.5”

It’s somewhat rare to see edgy, large-format contemporary watercolors in New York Galleries. The genre, if one could call it that, seems to have evolved organically out of a collision cultures. Ching-Bor began working large by standardizing on vertical, same-sized strips of paper reminiscent of the Chinese and Japanese ink painters, only putting them together for larger and wider pieces.

Ching-Bor studied traditional fine art at Guangzhou Fine Art University (China) and Jing De Zhen Ceramic Institute (China). During the ensuing decade, he lived and worked as professional artist in Sydney, Australia. In 1996, he moved to New York, where he studied painting and printmaking at the National Academy of Design and began to find his own voice.

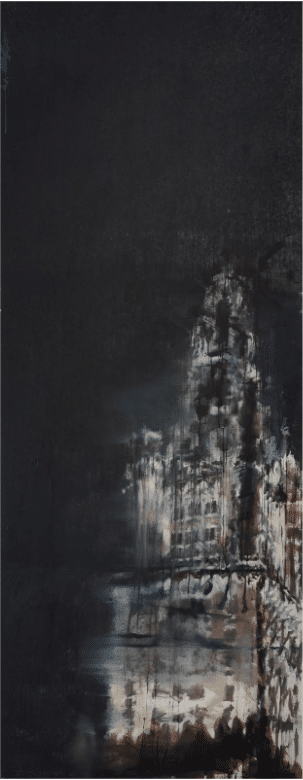

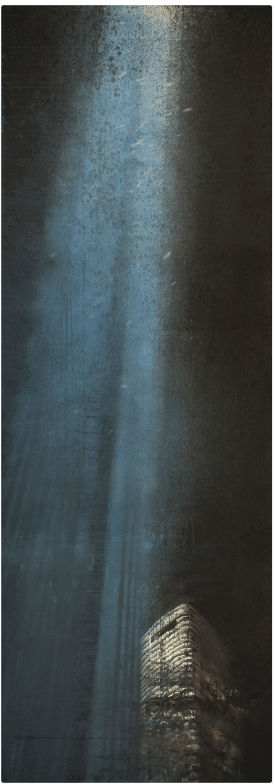

Paul Ching-Bor, The Onland Lighthouse VI, watercolor on paper, 126” x 51”

At some point, Ching-Bor fell under the spell of the New York School Abstract Expressionists, especially Franz Kline, whose gestural black-and-white abstractions can simultaneously resemble bridges and other city infrastructure as well as giant Chinese characters. In the works of Kline, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, and other artists of the era, Ching-Bor discovered deeper parallels with the theories of ancient Chinese scroll painters, a coalescence that has inspired his own personal blend of Eastern and Western approaches. In response to the city and its Ab-Ex history, his work went large scale, flying in the face of conventional watercolor principles.

“When I first walked down the streets of Manhattan I was curious about the impact this strident city and the jostling crowds would have on my work,” Ching-Bor says. “The structures, arches, and bridges immediately inspired me, and particularly suited my limited color palette. My favorite colors are black and white, and I found I was able to tackle New York subjects in a very free way that, in the early stages, suggests abstract painting.”

Paul Ching-Bor, INSOMNIOUS LIGHTS—THE WOOLWORTH BUILDING V, 2016, watercolor on Arches paper, 120 x 103 inches (in two panels)

His process involves laying down the fundamental part of the painting, which is the structure of the work. He then proceeds to glaze and splash paint on the paper until the image disappears. When the work dries, “the image bounces back,” he says. “Then I look at it again. The remains from the dematerialization become the new materialization of the work.”

The approach, the technique, and the role of watercolor they empower have disrupted the field no doubt will continue to advance the medium as time goes on.

Paul Ching-Bor, Abyss, watercolor on Arches paper 145 x 51 inches 2017

Chien Chung-Wei teaches watercolor street scene painting in a way that offers students a deeper understanding of the principles of composition to boot: on the video Spontaneous Watercolors, available here.

Realism, Abstracted

By Laura Vailati

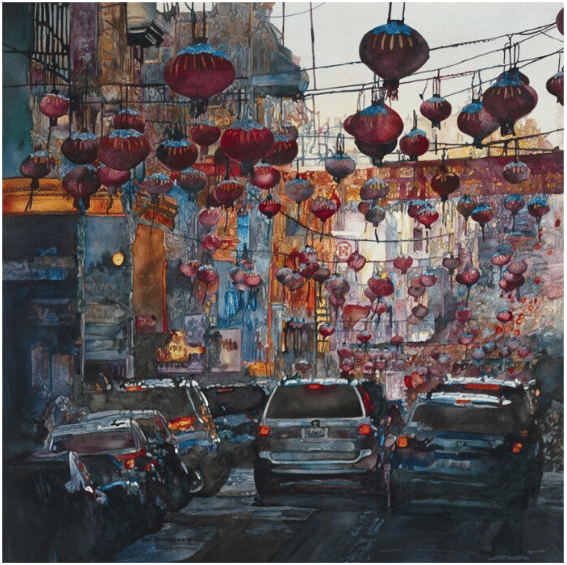

John Salminen, “New Year San Francisco,” watercolor, 36×36 in.

It is the studios, backgrounds, and creative languages that shape the style of major players in contemporary art. Artist John Salminen, whose unique style will be among the faculty members of the fourth edition of Watercolor Live, online January 24-26, 2024, is no exception.

From a great passion for drawing that was born when he was still a child and supported by the question, “What do I want to be when I grow up?”, the step was very clear from the beginning for John.

After drawing toy cars and copying illustrations in high school and greatly improving his technical skills, John attended the University of Minnesota, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts.