Have you ever stood listening in the winter night air for an owl somewhere off in the distance, surprised by the sound of your breathing, feeling the cold seeping into your feet? Why does that hollow, resonant call, especially in winter, so enrich the stillness and quiet of the night?

Good paintings can do that too, especially snow scenes and nocturnes. A nocturne is a night painting, often poetic, so called after James McNeill Whistler borrowed the term from the evocative piano compositions by Chopin. For Whistler, painting could be as much about feeling as music.

James McNeil Whistler, Nocturne in Grey and Gold: Chelsea Snow, oil, 62x47cm, 1876, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop

Sometimes a good painting, like a good poem, transports the viewer to a place somewhere between thoughtfulness and feeling, insight and memory, clarity and dream. It is a moment, perhaps, outside “knowing” or even meaning.

Quoted below, Mary Oliver’s poem “Snowy Night” revolves around this kind of inexplicable yet indelible impression.

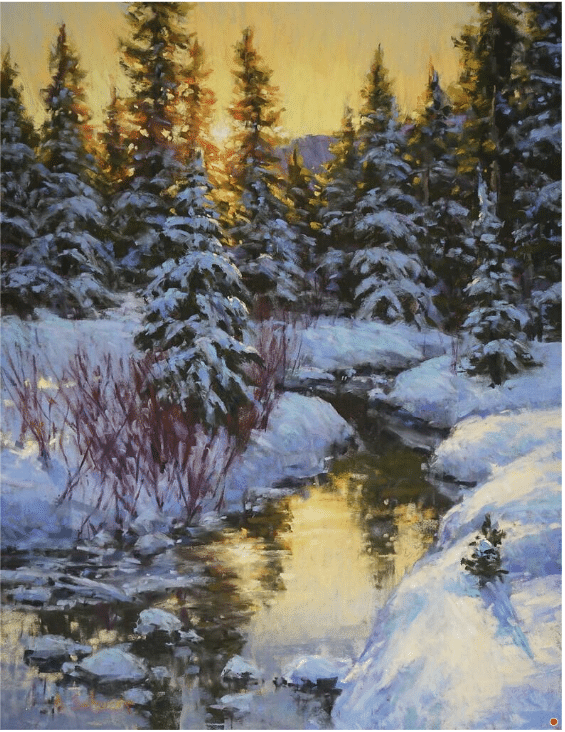

Aaron Schuerr, New Year’s Day ‐ Pastel ‐ Paper ‐ 18 x 14. Shuerr teaches his approach to painting the quiet snowy moment in his video, Winter Sunset in Pastel, which you can download here.

“Snowy Night”

By Mary Oliver

Last night, an owl

in the blue dark

tossed an indeterminate number

of carefully shaped sounds into

the world, in which,

a quarter of a mile away, I happened

to be standing.

I couldn’t tell

which one it was –

the barred or the great-horned

ship of the air –

it was that distant. But, anyway,

aren’t there moments

that are better than knowing something,

and sweeter? Snow was falling,

so much like stars

filling the dark trees

that one could easily imagine

its reason for being was nothing more

than prettiness. I suppose

if this were someone else’s story

they would have insisted on knowing

whatever is knowable – would have hurried

over the fields

to name it – the owl, I mean.

But it’s mine, this poem of the night,

and I just stood there, listening and holding out

my hands to the soft glitter

falling through the air. I love this world,

but not for its answers.

And I wish good luck to the owl,

whatever its name –

and I wish great welcome to the snow,

whatever its severe and comfortless

and beautiful meaning.

~ Mary Oliver

From What Do We Know: Poems and Prose Poems

(Da Capo Press, 2002), pp. 65-66.

Best wishes for a happy New Year!

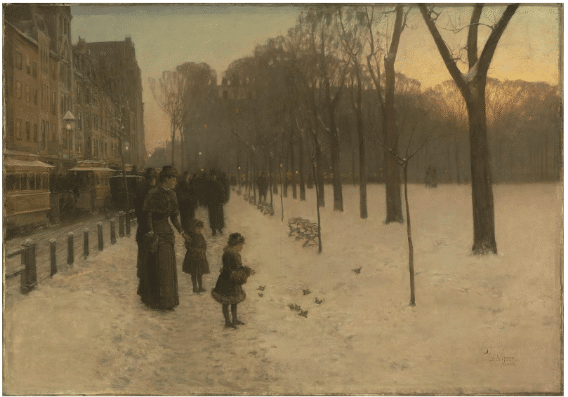

Childe Hassam, At Dusk (Boston Common at Twilight), 1886

Interested in the effects of light and shadow in snow at the “golden hour” at dawn or dusk? Aaron Schuerr teaches you what to look for, step by step, in his video, Winter Sunset in Pastel. Have a look here.

Want to Paint a Nocturne? Don’t forget Joy

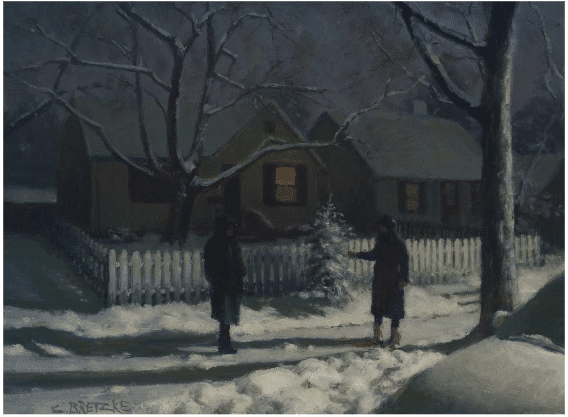

Carl Bretzke, “Winter Evening On The Block,” 2020, oil on panel, 9×12 in., Available at Grenning Gallery (NY)

Finding joy through painting is something artists, collectors, and connoisseurs certainly experience. Painter Carl Bretzke of Minneapolis, Minnesota, is no different, though joy is often combined with a sense of urgency when a scene captures his imagination.

The artist writes, “I think it’s important to be excited about what you paint. I can’t put my finger on exactly why a certain scene appeals to me, but I know that I experience a joyful sense of urgency when I see it. Often the scene will be some off combination of the mundane and the sublime. I then want to start the piece as quickly as possible before the light changes.”

Once the moment of inspiration strikes, the scene’s light, subject, and color dictate Bretzke’s creative process for his oil paintings. He says, “Technically, I rarely start any painting the same way anymore. Early on, I used a Payne’s gray underpainting taught to me by Joe Paquet. This allows me to draw and freeze the light effect quickly. As my skills have improved, I have eventually learned to shortcut the process by adding color earlier and keying in some light values early as well.”

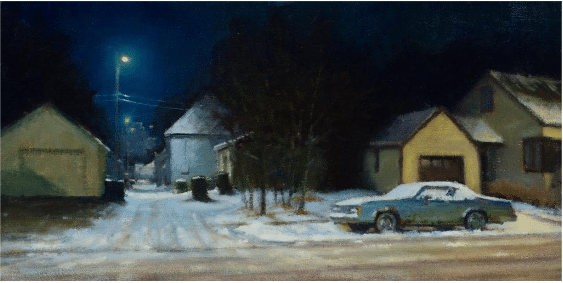

Carl Bretzke, “Pontiac In Repose,” 2020, 8×16 in., oil on linen, Available Grenning Gallery (NY)

As the painting evolves, knowing when the work is finished is perhaps one of the most subjective and challenging moments. For Bretzke, this moment is both technical and personal. He says, “I know when a plein air piece is completed when I feel like any additional paint will start to diminish the fresh feeling of the image or when my wife, Kristie (also a painter), says, ‘I’m hungry, you’re done.’”

In addition to working en plein air, Bretzke has a matured studio practice that allows him to work in a slower, more detailed manner. “I spend a lot more time analyzing and making lists of things to work on or change in the studio. It’s like this until I can’t think of anything else.”

As a writer for The Washington Post once remarked of Bretzke’s paintings, “They’re a little lonely and simultaneously intimate and detached.” The assessment seems apropos, as the artist’s landscapes and cityscapes are seldom populated with figures. The effect can be a ghostly one, but the absence of the figure only encourages the viewer to place himself or herself within the artist’s creative world. The pictures seem to invite you into their spaces while evoking feelings of nostalgia.

To paint a nocturne (outside and in the studio) from start to finish — no matter your experience level. Painting nocturnes can be frustrating and confusing without a systematic, step-by-step approach, In his video on painting the nocturne, Carl shares his personal “Six-Step System” for creating successful nocturnes consistently. Inside the course, you’ll discover “atmosphere-capturing” techniques, advanced “illumination brushwork,” his “Blended Method” technique to create gorgeous halos, and much more. Check it out now.