Lit by the moon, it looms like a phantom, the hoary captain of an unsinkable ghost-ship maybe, surveying the gray expanse of Northern Wilderness rolling endlessly into the horizon.

Standing 5 feet tall by nearly 4 feet across, Ivan Shishkin’s 1891 painting “In the Wild North” is one of pre-20th century art history’s largest paintings of a single tree. It’s a fantastic image; but what’s really going on here? Did Shishkin have to hike up a mountain in the snow at night to paint this? Why would someone want such a large painting of a pine tree anyway?

Shishkin came up through the Russian art academies, and in 1871 he joined the Peredvizhniki (“The Wanderers”), where his ideas about Russian landscape painting were met with enthusiasm. Shishkin’s friends called him “the czar of the forest,” “The Tree King,” and also the country’s “most patriotic painter.” His choice of primordially Russian landscapes as subject matter has endeared him as one of the most popular landscape painters in Russian history.

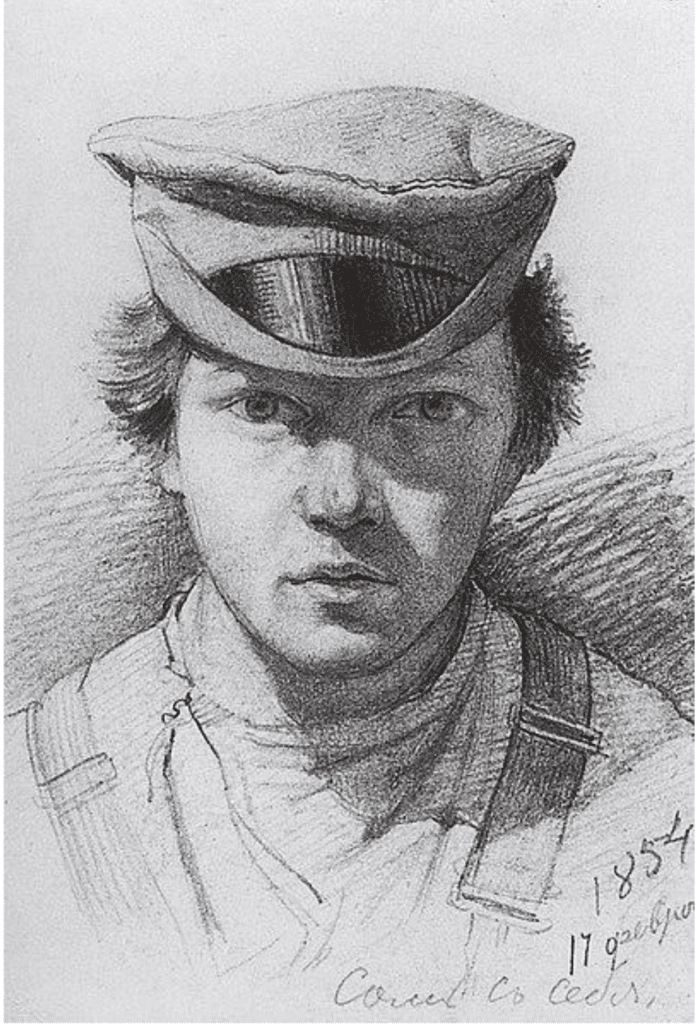

Ivan Shishkin, in an early self-portrait

In painting after painting like “In the Wild North,” Shishkin admonished the Imperial Academy’s rigid, out of touch approach, championing an art accessible to the people. He also rejected Impressionism when it arrived. He sketched natural forms outside but he was no plein air painter. I can hear him now dismissing Impressionism’s dainty touches and multicolored “atmospheres” as unworthy of the Russian artistic challenge.

Shishkin would insist on painting the majestic scale and solidity of his country’s primal geography with distinctly Russian iconography (often related to folklore) and a sense of monumental order. With that in mind, Shishkin’s clear-eyed, large-scale landscapes, such as “In the Wild North,” present the very image of epic Russian steadfastness — staunch, expansive, and rich, subject neither to human emotion and equal to time itself. This is not “reading into” the paintings (Shishkin himself plainly trumpeted his desire to paint Russianness) but rather a way of deepening our understanding of the artist’s mindset and his achievement by viewing it in context.

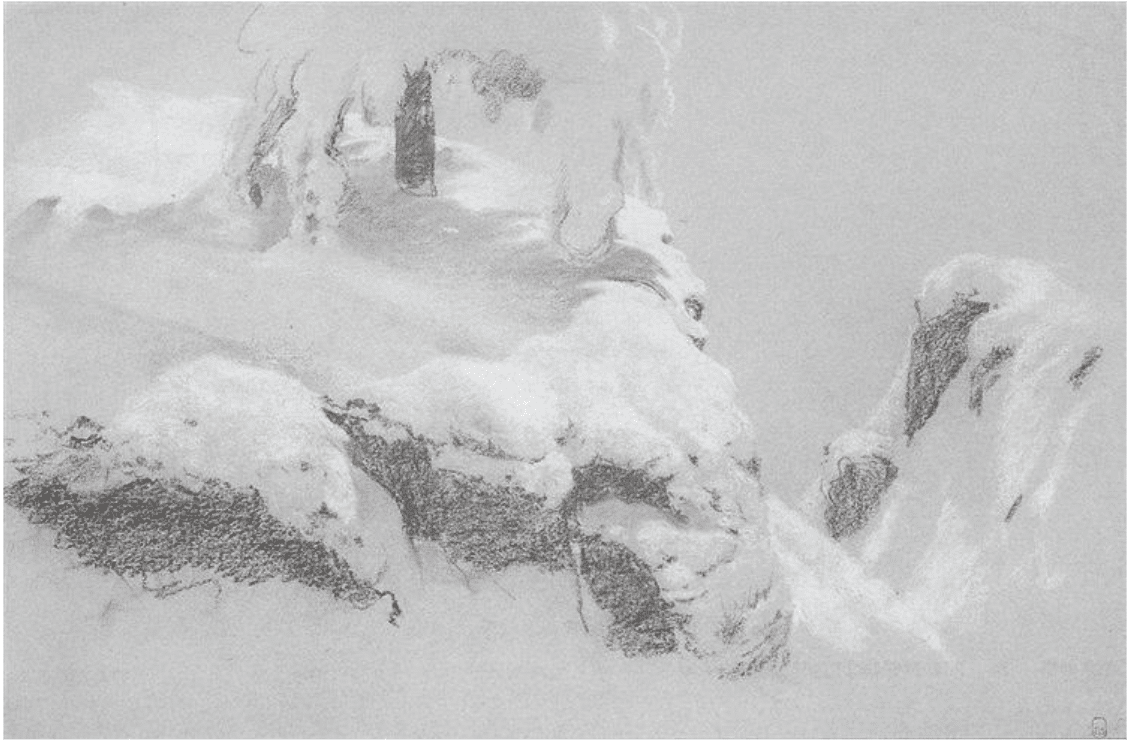

It’s interesting to see how Shishkin envisioned the main theme and composition of “In the Wild North” at the outset. His sketch for the bottom half of the painting indicates where the tree will stand in relation to the foreground shapes of snowbound cliffs and rocks (though as you can see by comparing the two, some of these foreground details ended up changing somewhat when the work went from sketch to painting).

Ivan Shishkin, sketch for “In the Wild North,” 1890

In case all of this snow and ice has got you wishing for sunnier days, Shishkin has an antidote or two for that. In “Mast-Tree Grove” of 1898, Shishkin celebrates the edge of a forest splashed with warm sunlight soaking the foreground. Of course, the title alludes to ship-building, and these trees themselves were a source of Russian pride.

The stalwart Russian Navy relied on Karelian pine, a native conifer of superior quality, for ship’s masts, a top choice of shipbuilders since the time of Peter the Great. Palace furniture, private chapels, and churches such as St. John the Divine in the Yaroslavi Region built from Karelian pine more than 300 years ago, still stand strong. So again we can see a patriotic dimension at work in Shishkin’s painting.

Ivan Shishkin, Mast-Tree Grove, 1898, oil on canvas, 165 x 252 cm

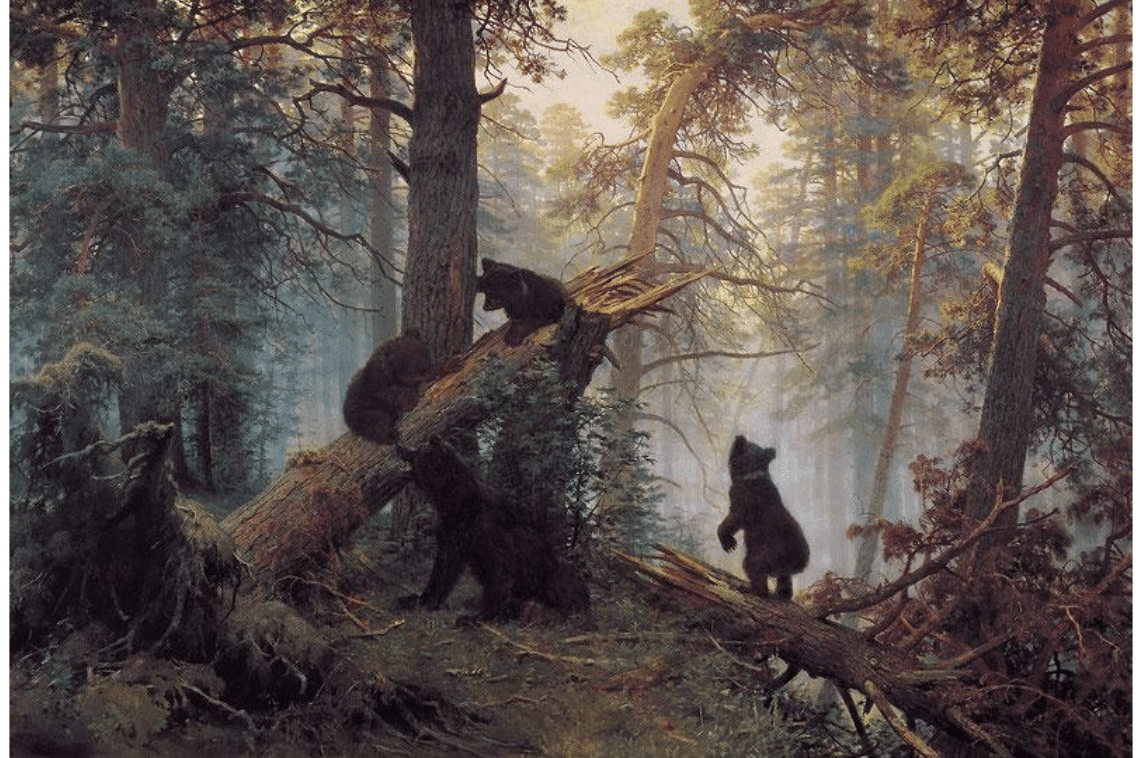

More iconic still is Shishkin’s Morning in the Pine-Tree Forest, depicting a mother bear and three cubs frolicking in a secluded forest clearing as sunlight burns off morning mist. The Eurasian brown bear, of course, has been part of Russia symbolism, representing the country in one form or another, since at least the 16th century. So beloved is Shishkin’s image in Russia today, that it’s long adorned the packaging of the popular Clumsy Bear ( ‘Mishka Kosolapy’) chocolate bars.

Ivan Shishkin, Morning in the Pine-Tree Forest, oil on canvas, 139 x 213 cm, 1889

However, in its reduced candy-wrapper form, some of the spirit, and many of the details of Shishkin’s painting appear to have been sacrificed to the rigorous demands of commercial illustration.

From 1873 to 1898, Shishkin became the professor of painting at the Saint Petersburg Imperial Academy of Arts. The Academy still operates today and is one of the most prestigious art schools worldwide, complete with a significant museum of paintings, sculpture, and plaster casts.

The Academy has maintained a reputation as one of the finest art schools in the world, training artists like Shishkin who became world-renowned, including Ilya Repin, Vladimir Makovsky, and many others. Together these artists were responsible for what has become known today as the “Russian Style.”

Today, the school, known as the Saint Petersburg Institute for Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, remains true to the vision of its founding in 1789: to train and prepare artists to reach their highest level of mastery, and only the finest artists get to become professors there.

One such teaching artist, Nikolai Blokhin, has a reputation as a leading portrait painter. He shares his approach to portraiture step by step in the “Russian Style” in his video, Russian Master Portraits. Download it here.

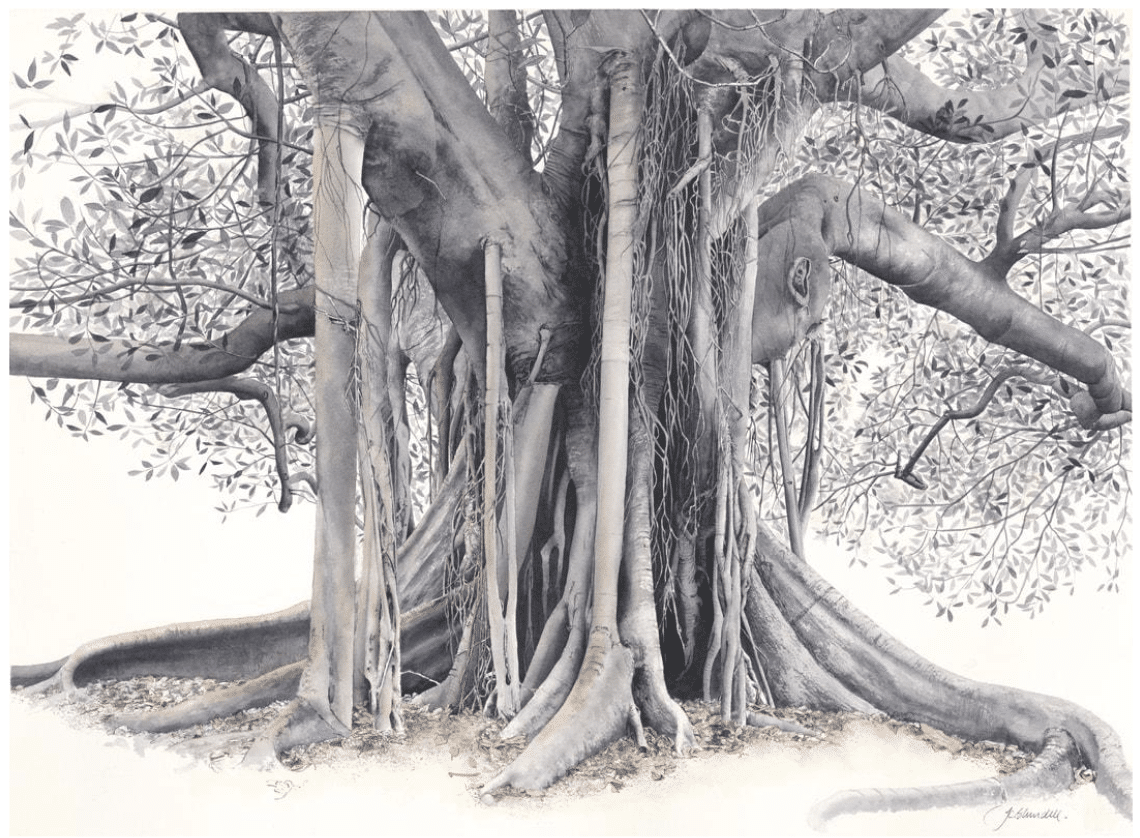

Falling Not Far from the Tree: Jane Blundell has a Passion for Trees – and Lots of Other Things Too!

‘Grounded’ watercolor and ink on paper. Image size 52.4 x 71.4cm

Jane Blundell has a way with trees. But then, she has a way with architecture, people, and animals too. She ought to; she’s had 40 years of experience painting and teaching with watercolors.

“I love running workshops and demonstrate,” Blendell says. “I’ve taught or demonstrated at the Urban Sketchers Symposiums in Singapore in 2015, Manchester in 2016, Chicago in 2017, Porto in 2018, Amsterdam in 2019 and Auckland in 223. I’ve taught workshops and sketched with the Urban Sketchers in many cities of the world, and for art and watercolor societies locally and internationally – I love to travel!”

Jane Blendell, a watercolor Kangaroo

She will be one of the many professional painters and teachers in “Watercolor Live,” a three-day online symposium of demos and workshops attended by thousands of people online. The event kicks off next week and runs January 24-26, 2024. Learn more here.