“My father wasn’t a religious man, but he found in the woods a sense of the divine in the beauty of nature. It was a place for solace and contemplation.” – Elaine Hibbard Clark, daughter of American landscape painter Aldro Hibbard

Aldro Thompson Hibbard (1886 – 1972) to many represents the essence of mid-20th century New England landscape painting in the realist/Impressionist mode.

He painted en plein air, with a big canvas and a sturdy tripod known as a Gloucester easel firmly planted in the ground. “Direct contact gives you the rare things,” he insisted. Hibbard rose pre-dawn and worked hard, in 20-below weather if that’s what was on the morning menu.

Once, he said. he left a canvas overnight, and when he returned the next day to complete it, the little stream he’d been painting had frozen over. “There was nothing for me to do but start the brook running again,” he said; so after an hour or more of chopping at the ice while the sun rose, he got the water running again and finished the painting.

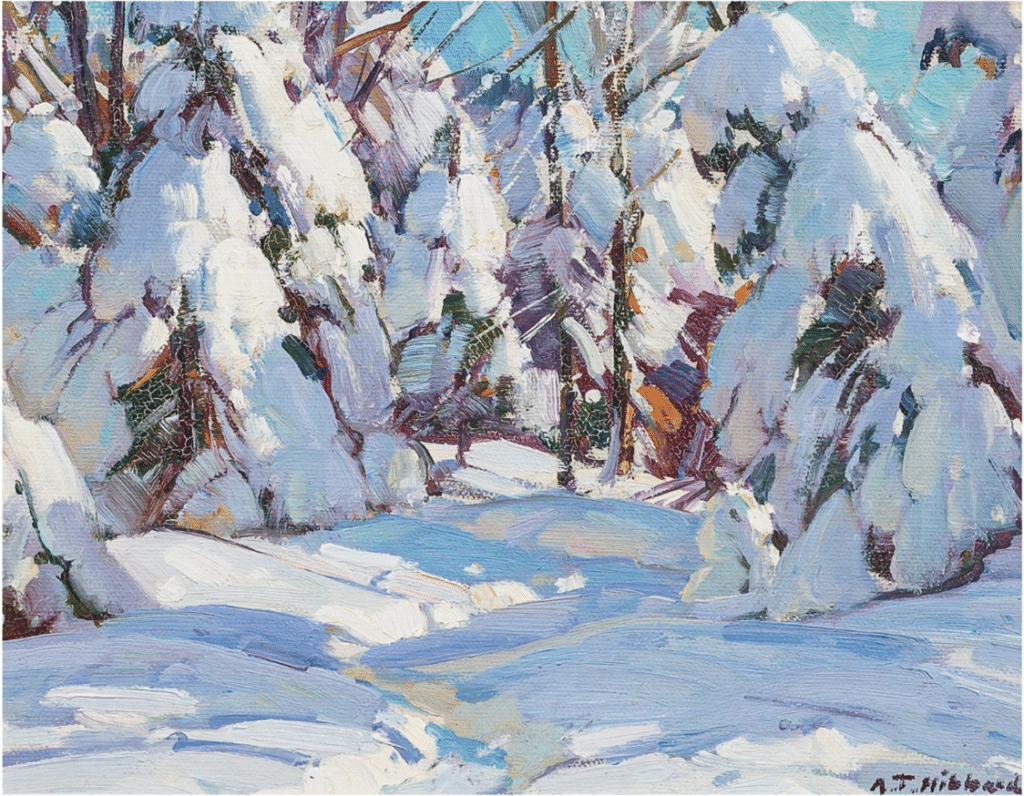

Aldro Hibbard, Morning Snow, oil on canvas, 8×10 inches

Detail showing brushwork of Aldro Hibbard’s Morning Snow, oil on canvas, 8×10 inches (above)

Hibbard was a conspicuously masculine, no-nonsense character, or at least that’s the image he cultivated. He is the quintessential outdoors(man) painter, squinting into the sun, intensely focused, ever-prepared to face down the elements, fortified by a rugged greatcoat, mittens on and ear flaps down, with a Clint Eastwood™ cigar clamped between his teeth.

As Irma Whitney writing for the Boston Herald said, at the time, “With breezy directness, this New England painter goes after Nature in the rough.”

Aldro “Do You Feel Lucky Punk” Hibbard

His paintings certainly present a frank and substantive approach to conveying his observations and experiences of the natural world. He matriculated at Boston’s Museum School (where he studied under the urbane Boston School impressionists Joseph DeCamp, Edmund Tarbell, and Frank Benson). In just a few years’ time, his combination of ability and charisma had him headed for the ranks of “the foremost landscape painters in America,” effused a critic for The Boston Globe. Hibbard was “certainly in a class by himself when it comes to painting New England winter scenes,” the writer remarked. “He is a realist in that you feel the reality of everything he paints, but the sentiment, the poetry is there also.” His colors are outstanding.

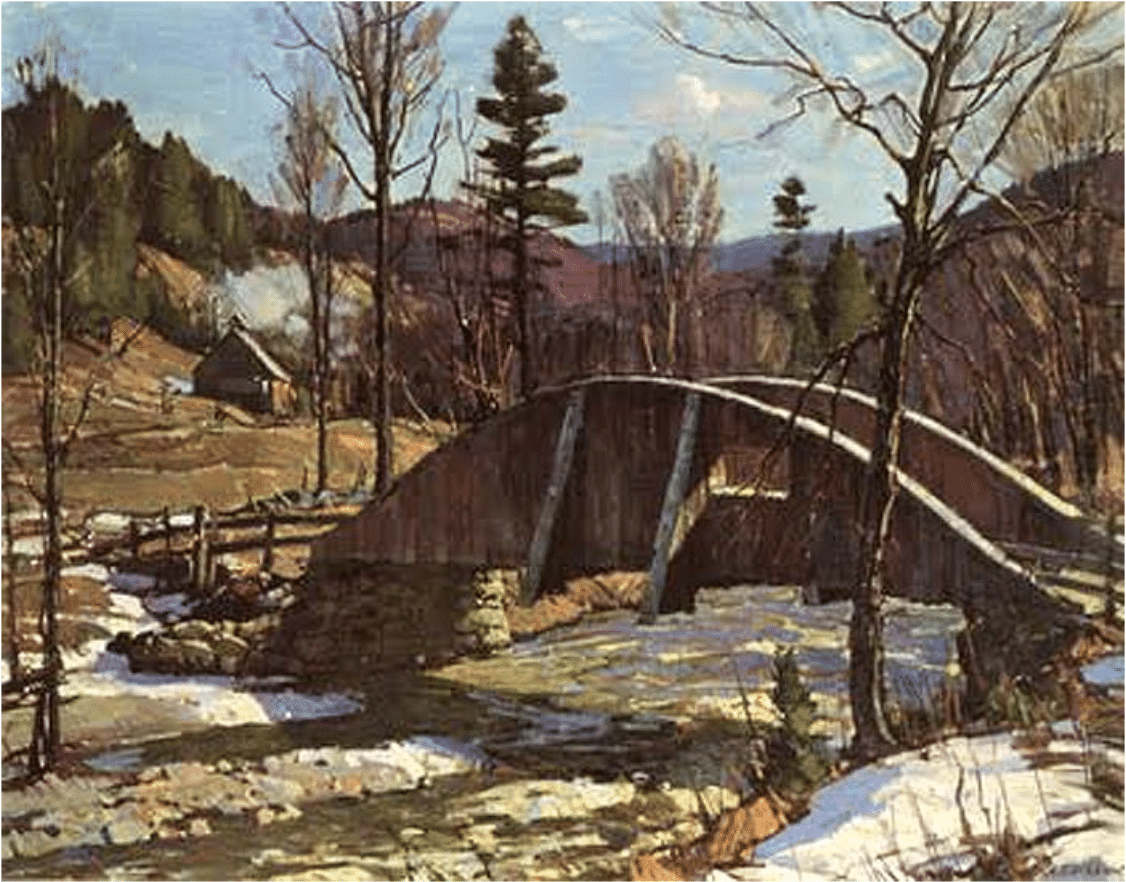

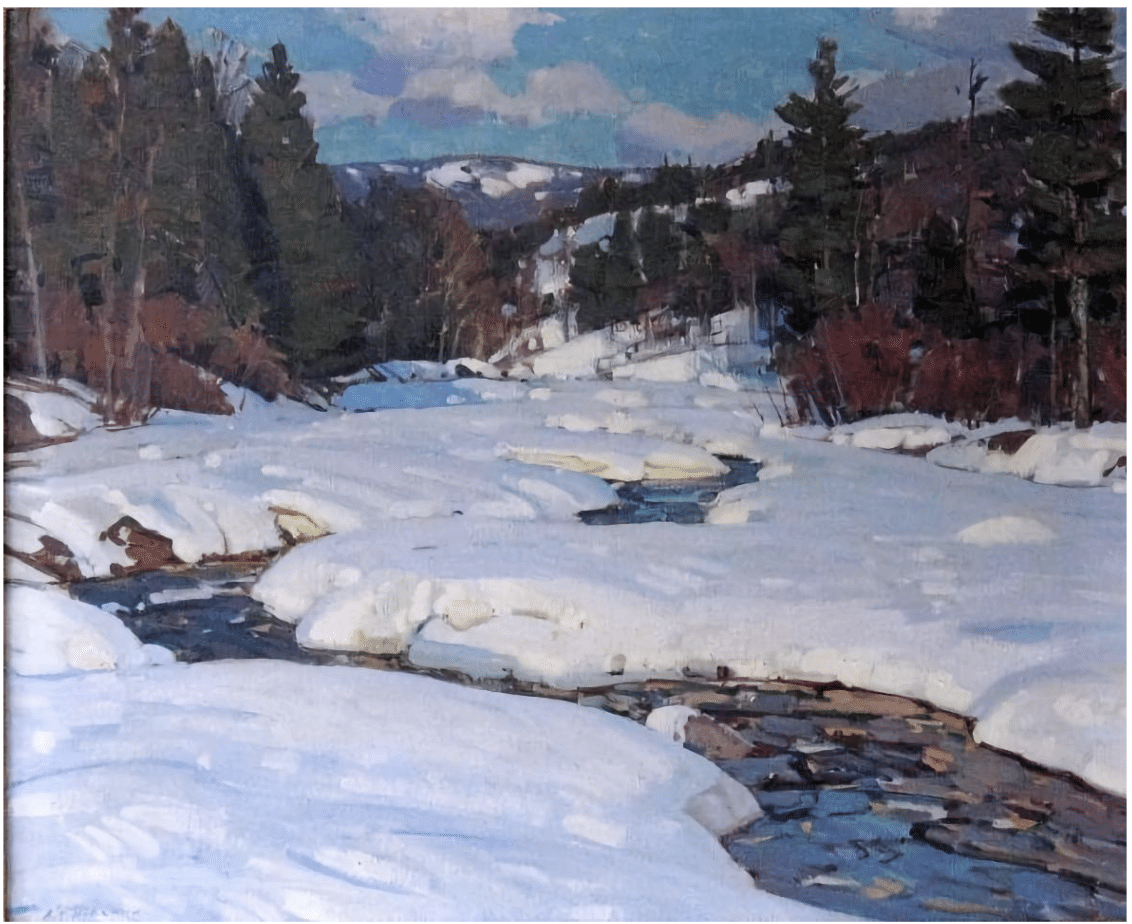

Aldro Hibbard, Winter Stream, 24.25″x 30″ – Oil

As for winter scenes, Hibbard spent the warmest part of his painting year on the Massachusetts coast and the colder part – that would be spring, fall, and winter – in even colder Vermont. From his northern outpost, he relished the hardships of primitive plumbing, a creaky woodstove, and all the curious rituals of Vermont winter life. He loved to hail an early morning logging team and catch a ride to some remote location in the hills, and sometimes he used his transportation as subject matter.

Aldro Hibbard, Loading on Logs, approx. 25″x 30″ c. 1928.

One critic at the time, J.H. Waver, Sr. writing in Today’s Art, described Hibbard’s landscapes as “not of the pretty, imitative sort, no mere slavish copy of appearances. He gives us the heart, the soul of the New England countryside, a vision both intimate and aloof. Viewing his snowscapes, one is tempted to breathe deep the bracing winter air – astringent; challenging but also inciting – which emanates from the canvas.”

Hibbard, though, didn’t just paint snow. “To think of Hibbard as merely a painter of snow… (Oh! But what a snow painter he was!)… would be a mistake,” says contemporary artist John Pototschnick in a blog-post on Hibbard (an excellent, far more thorough and well-rounded article than this one, which you should read here<< https://www.pototschnik.com/aldro-thompson-hibbard/ ). “He was basically a landscape painter who also excelled at figurative work … but the thought of doing portraits for a living just didn’t sit well with this athletic, love of the outdoors kind of guy.”

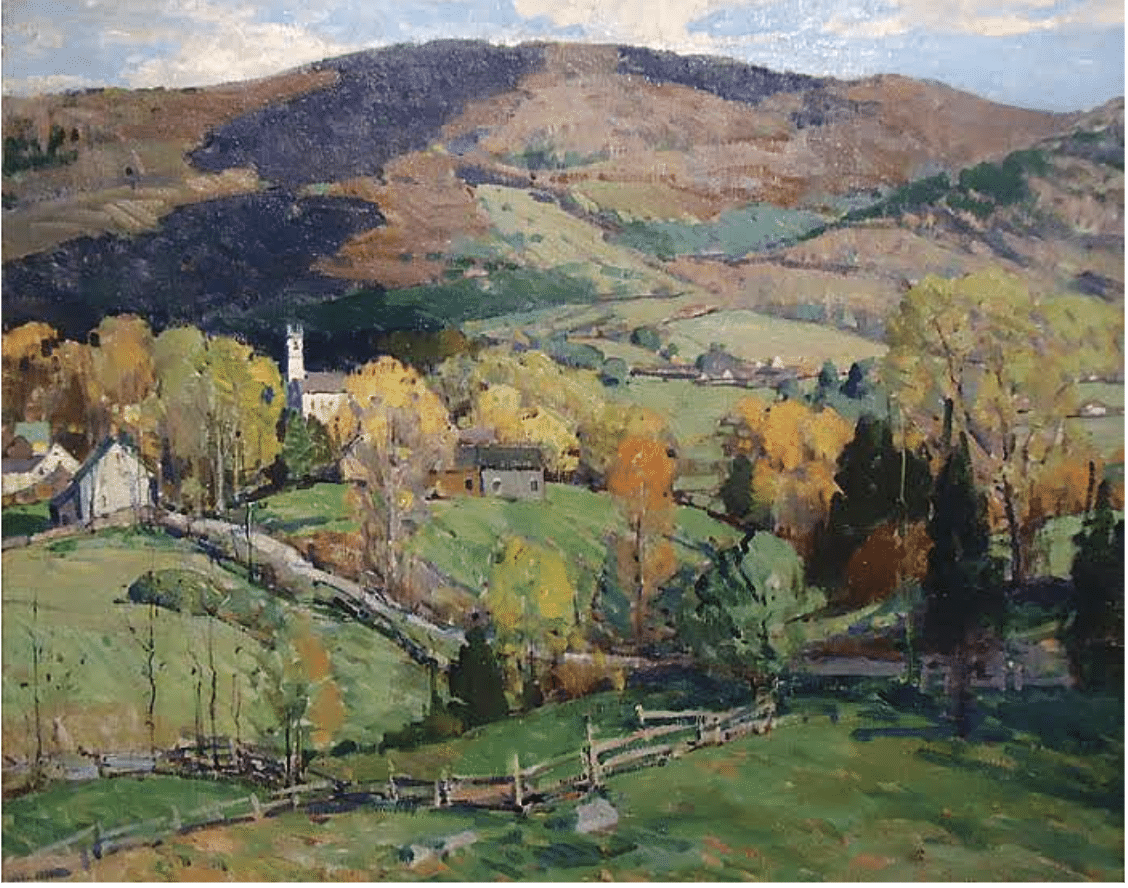

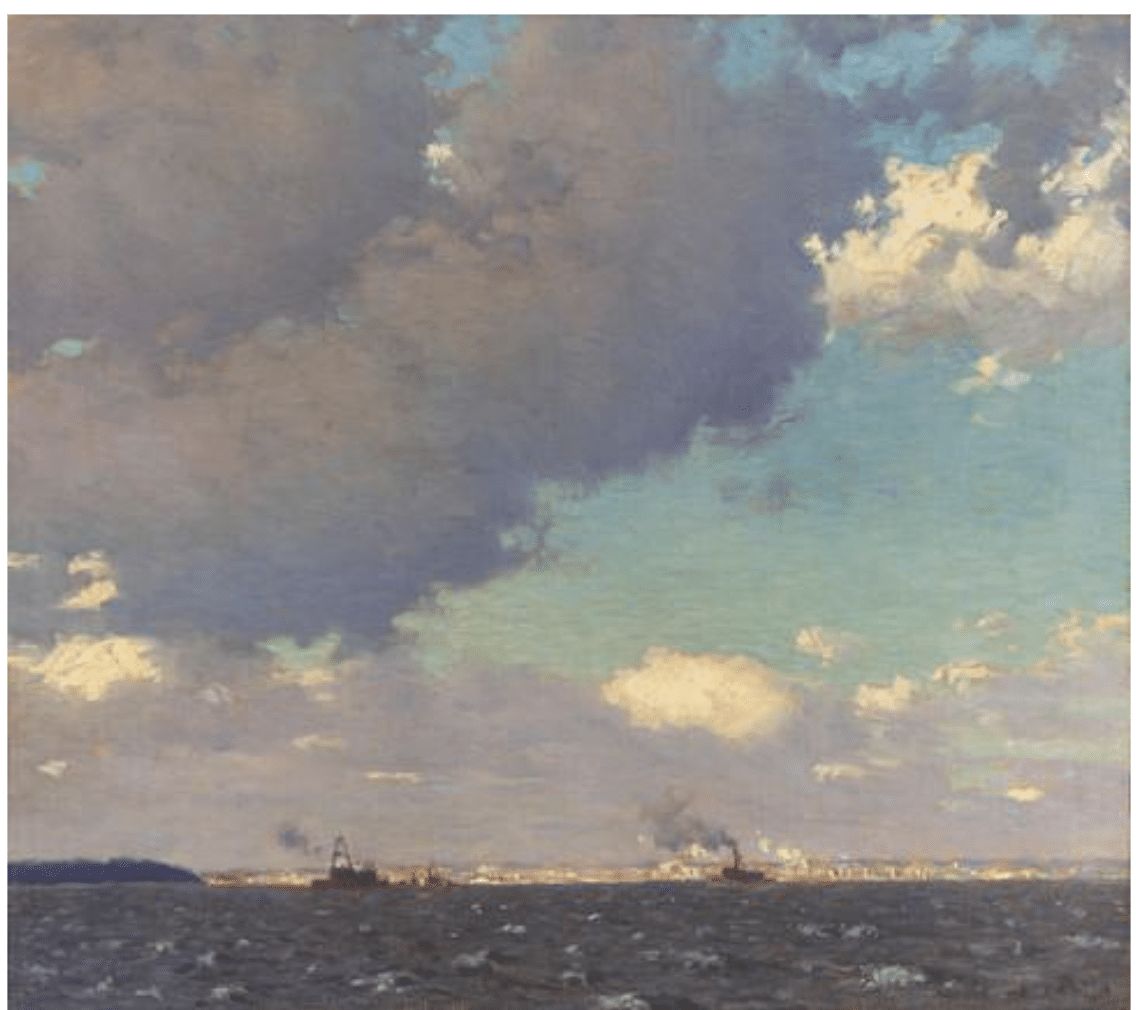

He painted sun-drenched farms, fields, trees, lakes, and in his summer haunts of Rockport and Cape Ann, boats and ocean shores. But then, as now, he was especially revered as a snow painter.

Hibbard used a moderately restricted palette, but he was quite private about his painting. While he said he normally had no more than eight or ten colors on his palette, he also said they were “not always the same colors” each time. Rather, which colors he put out depended on the subject and the quality of the light that day.

No matter the season, Hibbard’s landscapes exhibit an immediately recognizable style marked by bright yet earthy and harmonious colors and rounded forms arranged in crisscrossing diagonals. Instead of straight or concave lines, his swelling, muscular masses tend to bulge and nestle against each other rather than lying down and behaving like the flat puzzle pieces some of his contemporaries relied on. John Pototschnick quotes Tom Nicholas N.A., on this aptly saying that Hibbard “painted anatomically, structurally. One could sense the anatomy of the landscape.”

During the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s, thousands attended his Hibbard Summer School of Painting and Drawing (modeled on Charles Woodbury’s summer outdoor painting school in Ogunquit, ME). He was an important member of the loosely knit group of painters who put Rockport, MA (home of “Motif No. 1”<< https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motif_Number_1 ) on the map as a major artist’s colony and painting destination, for a while second only to Monhegan Island in Maine.

Hibbard showed at The Guild of Boston Artists where he was a member, the National Academy of Design in New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia as well as various commercial galleries. He founded the Rockport Art Association, sold well and taught packed outdoor painting classes until his death in 1972, a beloved, civic-minded member of the Rockport community. (A baseball team he founded there kept going for 40 years, just about all of which found Hibbard at bat.)

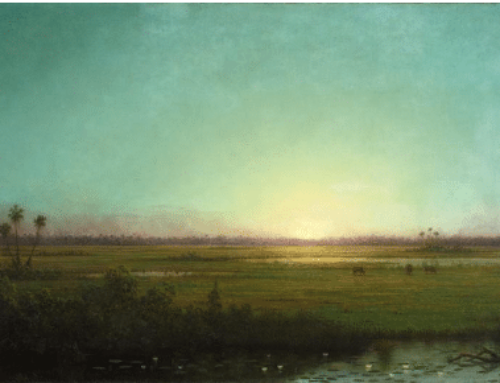

Aldro Hibbard, Clearing, Buzzards Bay 25 1/4 x 28 3/8 in. (64.1 x 72.1 cm.)

Last Words

As for do’s and don’ts and tips and tricks, we’ll let “Hibb” as friends called him, have the final word: “Avoid excessive use of juice,” he advised, by which he meant turps or varnish. “It floats the paint on and dries flat and uninteresting. Use a lot of pigment. Get vibration. A rough canvas helps. Strength in a picture comes from values. Color intensifies it. Paint with speed. Use up your nervous energy. A morning’s painting should wear you out.”

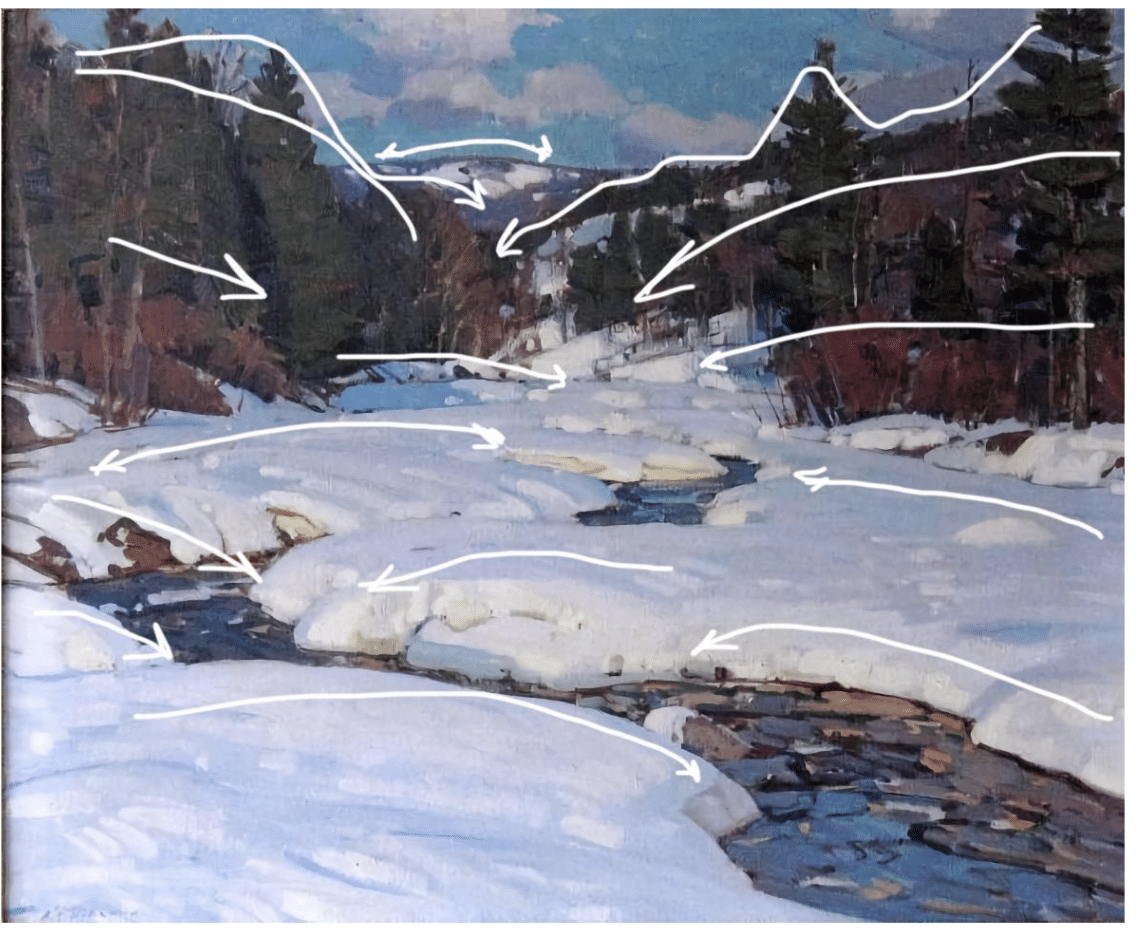

Here’s an image of one of Hibbard’s snowy Vermont paintings showing the muscularity of his forms, composed of stocky, humped and rounded lines all seeming to converge toward the painting’s center.

And here it is again without the obstructing diagrammatic lines, better to appreciate his real mastery of the snowy landscape’s rich colors, varied lights, shadows, temperatures, and textures.

If this kind of painting is for you and you’d like to to try your hand, one place to start is John Pototschnick’s video on his own limited palette technique, including Limited Color Landscapes, available here.