A look at the marine paintings and life of historic master Emil Carlsen

Nordic Reflections: The Marine Paintings of Emil Carlsen

By Valerie Ann Leeds

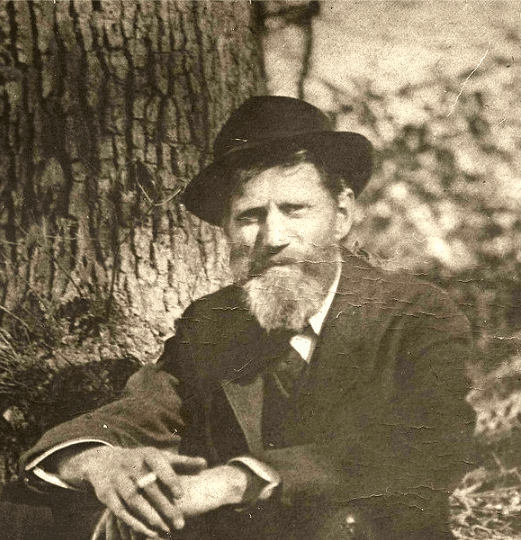

Lyricism, quietude, subtlety — these are the defining qualities of the landscape paintings of the Danish American artist (Søren) Emil Carlsen (1848–1932). In his lifetime, Carlsen was far better known for still life subjects, and the misconception that this was his primary genre has prevailed. In fact, landscapes represent a significant aspect of his production, including exceptional marine scenes painted throughout his career.

Warranting particular reappraisal are Carlsen’s compositions picturing open seas, coasts, and falls, which earned critical acclaim and bound him artistically to his Nordic seafaring heritage. Indeed, his life-long connections to Denmark supplied an essential foundation for his art and especially informed his marine paintings.

Carlsen was born in Copenhagen and studied architecture at the Royal Danish Academy for four years. He then turned to art, and although the circumstances prompting this shift are unknown, art was part of his heritage, as his mother and brother were painters. Carlsen studied under the marine painter Christian Vigilius Blache (1838–1920) from 1866 to 1869, but in 1872 he immigrated to the United States and settled in Chicago, where he trained with another Danish-born marine painter, Lauritz Holst (1848–1934). He also studied in Paris in 1875, and returned there from 1884 until 1886.

Although Carlsen developed a unique style, the influence of the two older Danes and the traditions of his homeland are evident in the emphasis he gave to the natural world (especially open space, water, and sky), in his minimal and harmonious compositions, and in their entrancing light and atmosphere. All are features found in much Scandinavian art.

Early Marine Scenes

In 1876, the earliest published account of Carlsen’s marine paintings appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript (he moved to Boston that year after living in Chicago for four years): “Carlsen … has two or three pictures nearly completed which will soon be placed on exhibition in one of our galleries. They are marine and shore views and are remarkably effective.”

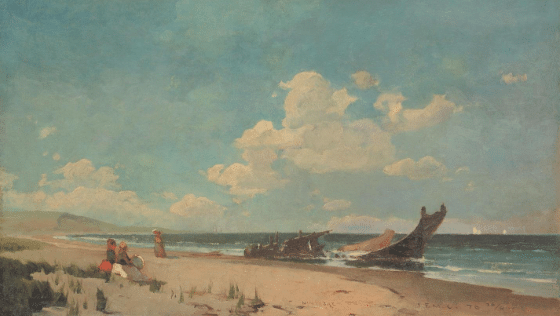

Emil Carlsen, “Nantasket Beach,” 1876, oil on canvas, 15 1/4 x 26 5/16 in., Art Institute of Chicago, Friends of the American Art Collection, 1940.1087

His most noteworthy early water composition is a Massachusetts scene with a boat wreck on Nantasket Beach (1876). Created when he was only 28, it is arguably Carlsen’s first mature painting and possesses many of the hallmarks that became essential to his seascapes — the open and spare composition, wide expanse of sky, and horizontal stripe of land. The subtle palette and thin application of pigment are also typical of the technique seen in his early landscapes, but differ markedly from the dark, somber tonalities of his still life paintings.

Duncan Phillips, the critic, philanthropist, and (Carlsen’s later) patron who founded Washington, D.C.’s Phillips Collection, explained how the artist’s interest in landscape developed, noting that his early landscapes were executed in a manner that was “rather thin and tight, but of a fine tonality and sensitively observed. In those days, no one cared for ‘still life’ and he could not sell his canvases. The world might never have known his landscapes and ‘marines’ if the struggle had not become precarious, so that his friends advised him to abandon ‘still life’ for more popular subjects.”

A still life in oil by Emil Carlsen. Carlsen’s still lifes harkened back to European Old Master models.

Carlsen had painted maritime subjects even while in Denmark, as early as 1870. Once in America, he attempted to establish his reputation with still lifes; in fact, he submitted them almost exclusively to major annual shows at the National Academy of Design and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through the turn of the century. Yet, he continued painting waterscapes, as noted in 1883 in the Boston Sunday Globe: “It will be a loss to one branch of art if Mr. Carlsen gives up his still life-work [sic], but if he succeeds as well with marine subjects the gain will quite evenly balance the loss.”

After 1900, Carlsen became increasingly engaged with landscape and marine compositions and began showing fewer still lifes. It is possible that this shift was influenced partly by his friendship with American impressionist J. Alden Weir (1852–1919), which commenced around the same time. The two artists shared a poetic and suggestive approach to painting nature, although with different results.

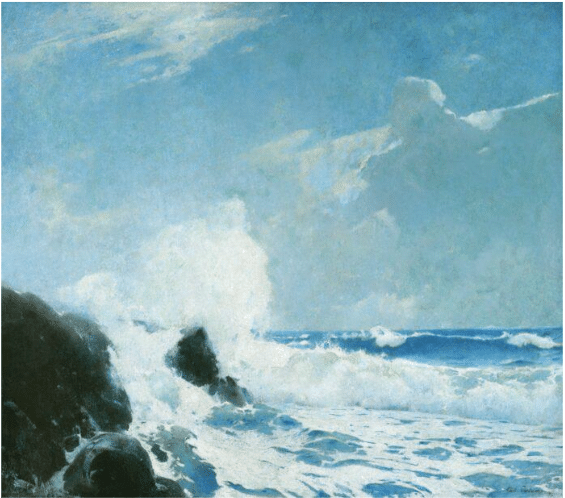

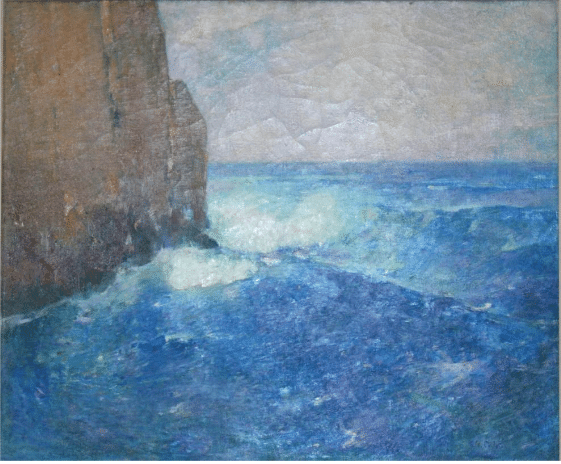

Emil Carlsen, Coast of Maine, c. 1910. Carlsen painted many paintings of Bald Head Cliff, a dramatic bit of rocky coastline in Cape Neddick, near Ogunquit, Maine. Then as now a large hotel stood perched overlooking the crashing Atlantic waves – a perfect base for a series of plein air tributes to the wildness of the sea.

Continue reading this article in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine (November / December 2022 issue)

Marine painting is very much alive and well. A modern master of the ocean, Don Demers, will teach you all you need to know in “Mastering the Sea.” Or check out an array of seascape techniques in the videos available from Streamline, here.

Simple Shapes Get the Job Done

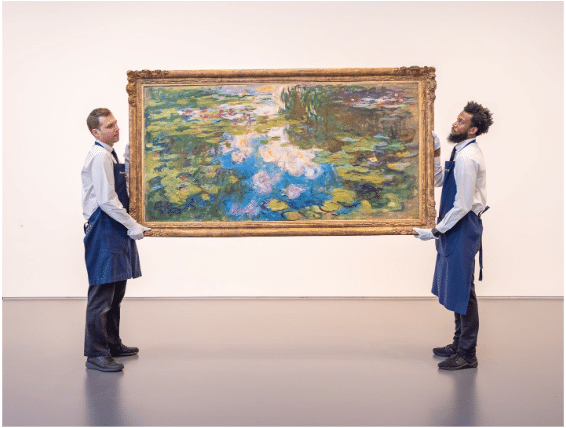

Claude Monet’s Le Bassin aux Nymphéas (1917-1919), which was publicly auctioned by Sotheby’s a few years ago and sold for $74M.

Although at first glance this painting by Claude Monet (like many of his paintings) may seem chaotic or “random,” amorphous and semi-abstract, even lacking in compositional structure. When you think of Monet do you automatically think of masterful composition? I don’t – I think of incredibly poetic color and brushwork and often the dissolution of forms into atmosphere – but it’s there!

Case in point, if we break this painting down, we find just three large, simple shapes. There’s plenty going on inside them, but there they are – three big, wide, simple shapes. We don’t get a standard textbook, academic composition or even a variation on one (such as Monet’s friend J.S. Sargent often gives us). But just because it doesn’t have a rigorous or readily identifiable compositional strategy doesn’t mean it’s a bad composition. It’s just different – original to Monet, and perfectly suited to the lyrical flow of color and paint-shapes at the heart of his feeling for painting.

Here’s a diagram – the lines and crosshatching are there just to distinguish the three main shapes, not to indicate anything else.

Diagram of the composition of Claude Monet’s Le Bassin aux Nymphéas (above)

So, that’s what they mean by “big simple shapes.” Sotheby’s has a masterful short on this painting, btw, that places it in the before and after of Monet’s illustrious career, which you can watch here.