“My decorations belong to the poetic and imaginative world where a few choice spirits live.” – Thomas Wilmer Dewing, from a letter to Charles Lang Freer dated February 16, 1901.

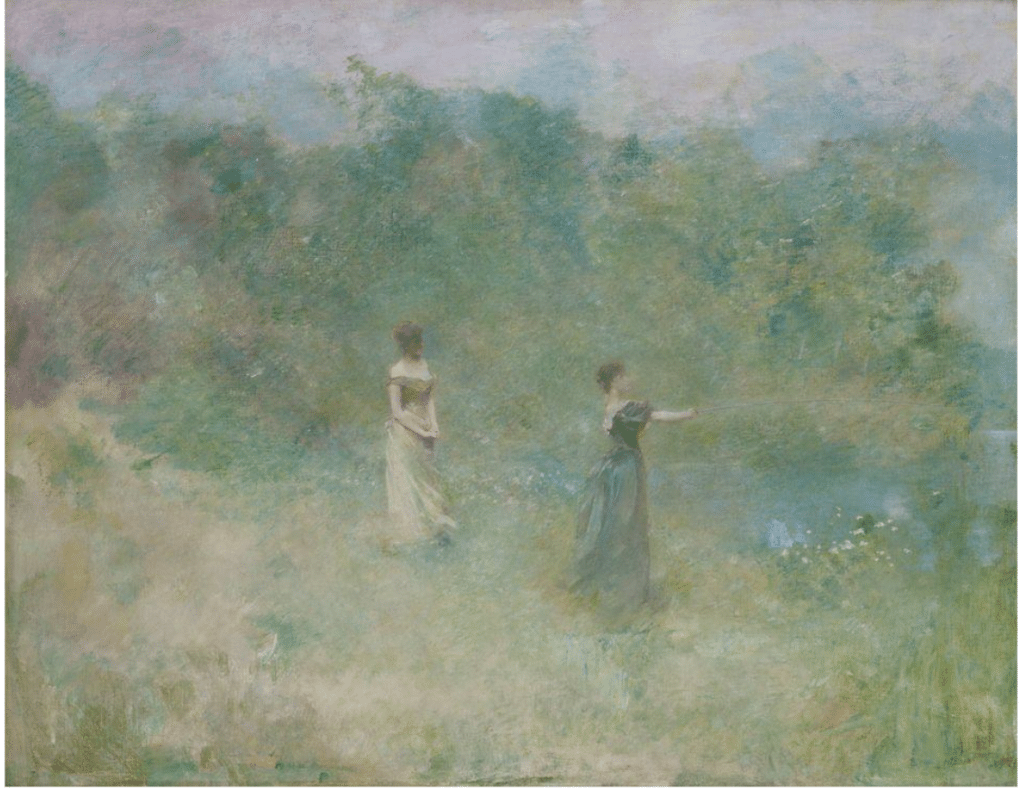

Inspired by his summers in Cornish, New Hampshire, Thomas Wilmer Dewing made a series of a dozen or so enigmatic paintings between about 1890 and 1904 showing female figures surrounded by a gauzy, mystical atmosphere.

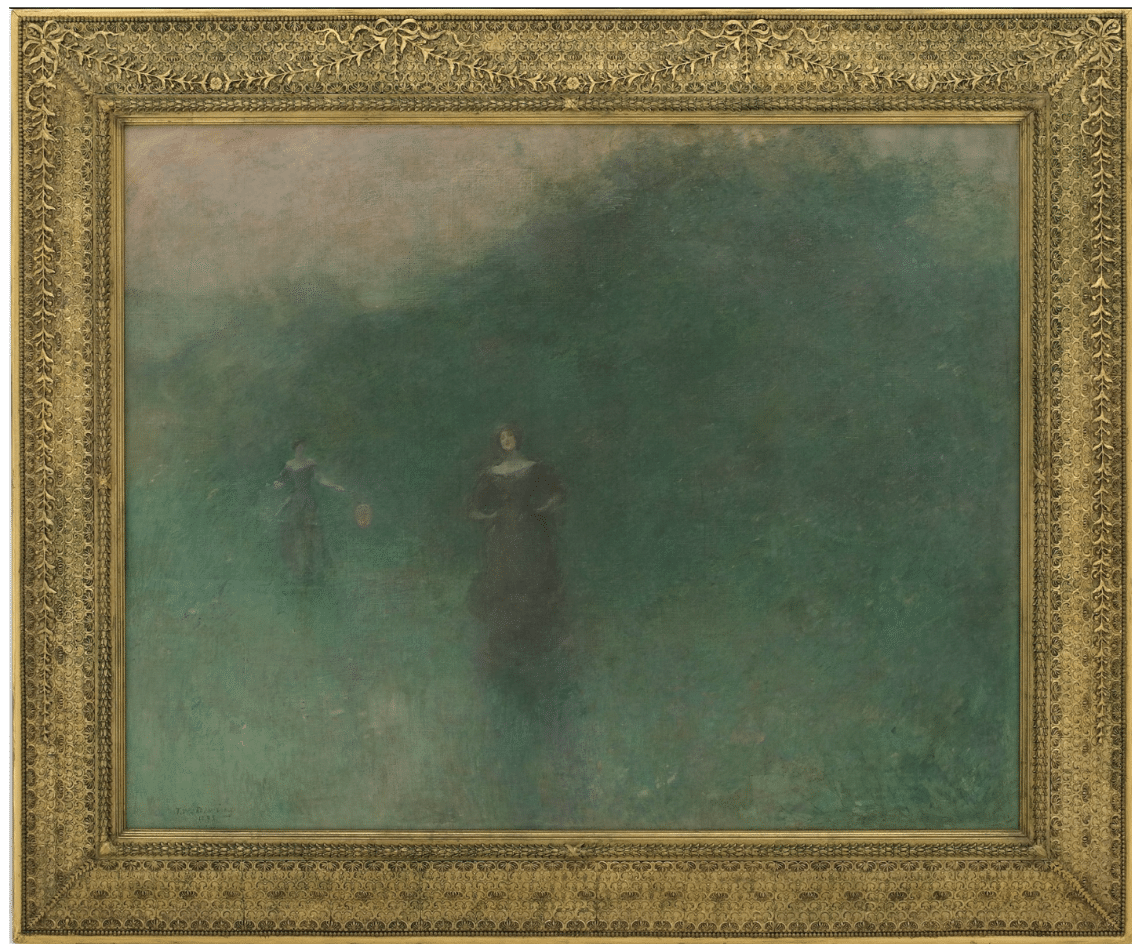

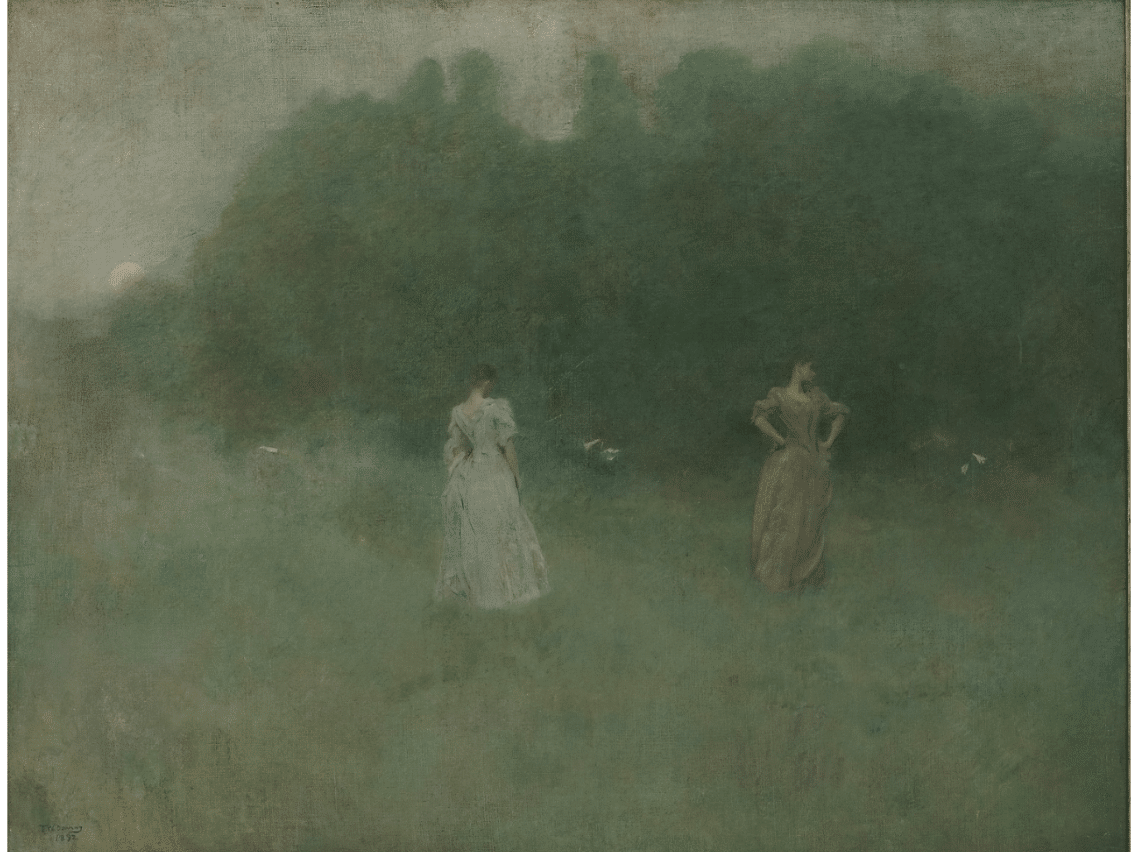

Dewing created Before Sunrise of 1894-95 (above), and its companion piece, After Sunset of 1893 (end of article), In Before Sunrise, two women emerge from a soft field at dawn, enveloped in mist glowing with the first rays of the sun. As most of the women in this series, they don’t relate to each other, each enclosed in her own psychological world. Are they together or part of a group outside the frame? The woman in the background carries a Japanese paper lantern; a poetic allusion, perhaps, to the soon-rising sun?

Detail of Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Before Sunrise

In Before Sunrise and other paintings of the period, the flattened picture plane of Japanese printmaking influenced Dewing and many of his contemporaries; not unlike Whistler, Dewing paradoxically substituted a sense of depth for the potential of two-dimensionality revealed by the Japanese print. The dresses and props are modern, but the amorphous tonalistic setting could be anywhere, or any time.

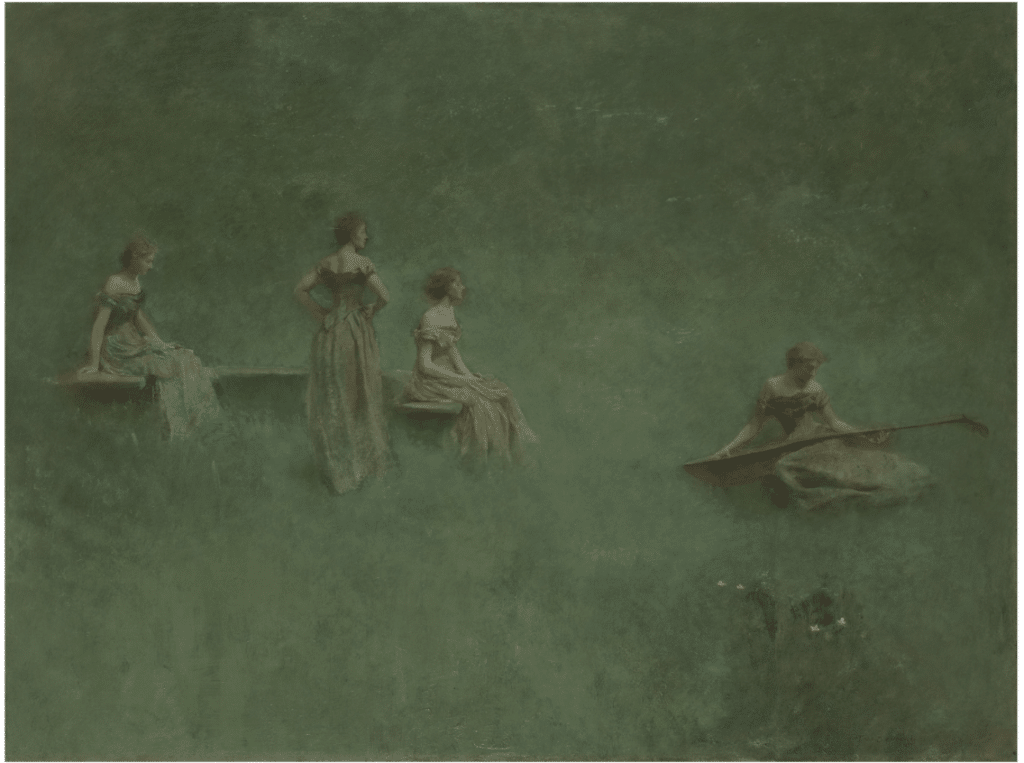

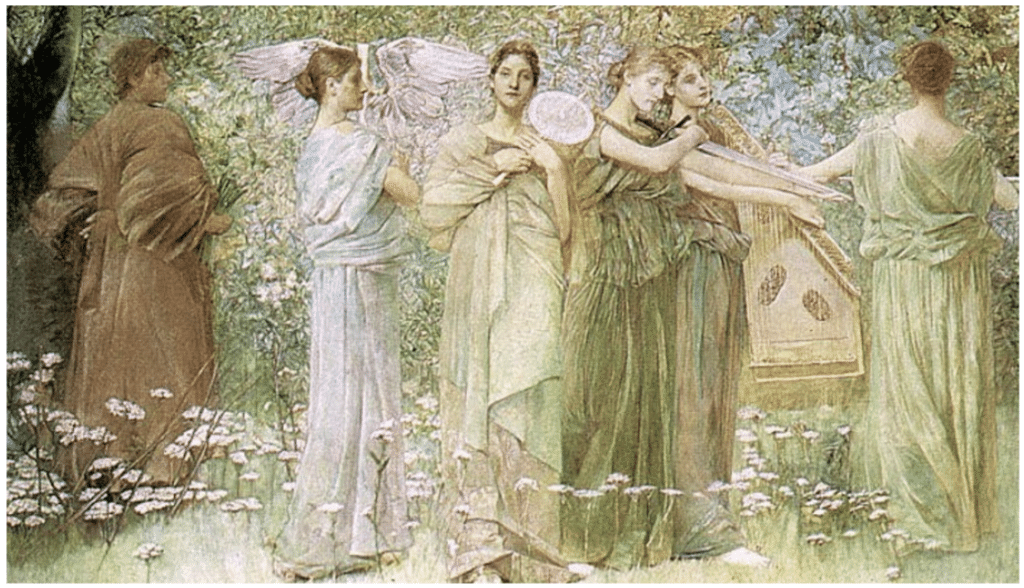

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, The Lute, oil, H x W: 91.5 x 122.1 cm (36 x 48 1/16 in)

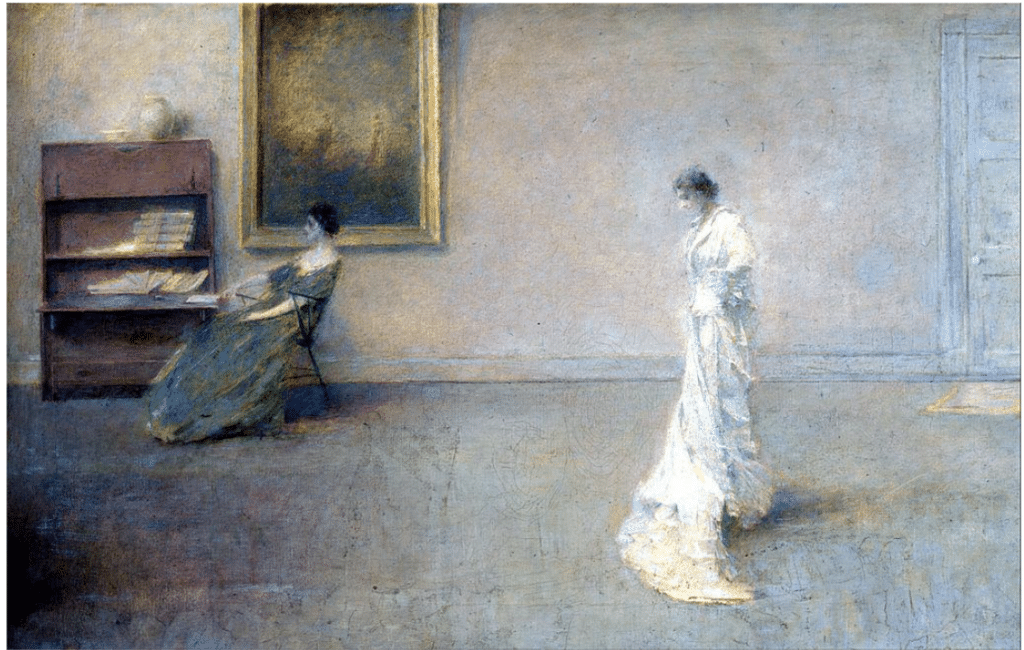

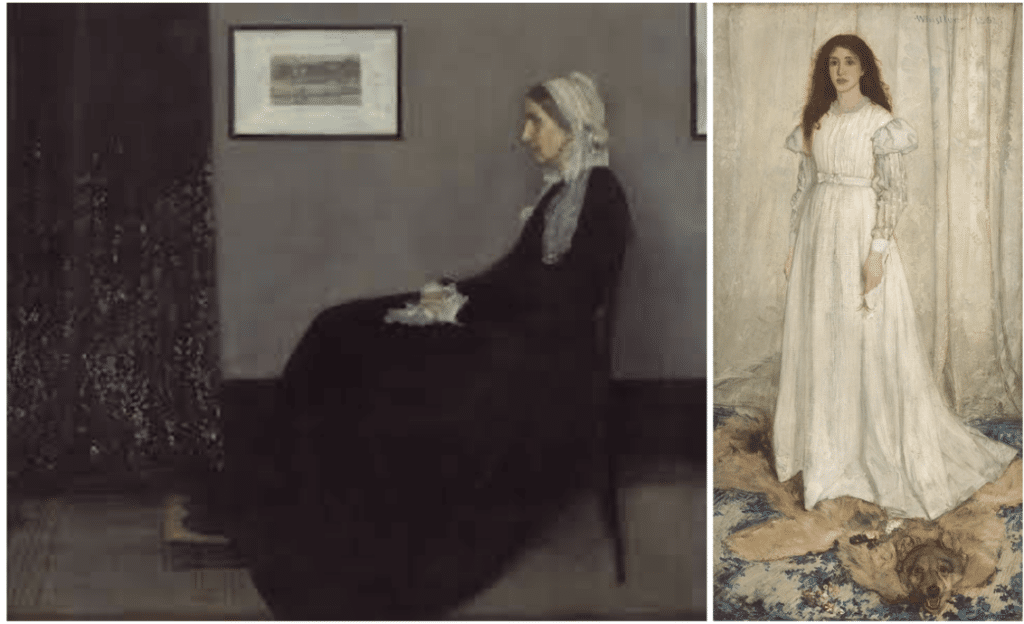

Dewing’s The White Dress of 1901 (below) seems to contain multiple allusions to Whistler as well a sly nod to his own work. The standing woman recalls Whistler’s multiple women in white dresses (such as Symphony in White no. 1: The White Girl), and the seated figure in profile on the left reminds us of “Whistler’s Mother” (Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1: The Artist’s Mother), both from the 1870s. However, in Dewing’s remix the painting on the wall behind the sitting woman is not one of Whistler’s but clearly one of his own, and from the same dreamscape series of women in mysterious natural settings he was in the midst of creating.

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, The White Dress, 1901 w36.5 x h27.5 x d2.5 in (Frame)

James McNeill Whistler’s Portrait of his mother and “The White Girl.” Mid-1870s

Unlike Whistler, Dewing didn’t use glazes of transparent oils. Dewing didn’t talk much about the practice of painting at all, so it took art historians to unravel the mystery of how he made these paintings. X-rays reveal he used a classical ebauche that he learned in Paris; he began by laying in a mosaic of loose lights and darks that he then linked with intermediate hues. As the painting neared completion, he pulled the more detailed images out, using white for contrast with the tonal background.

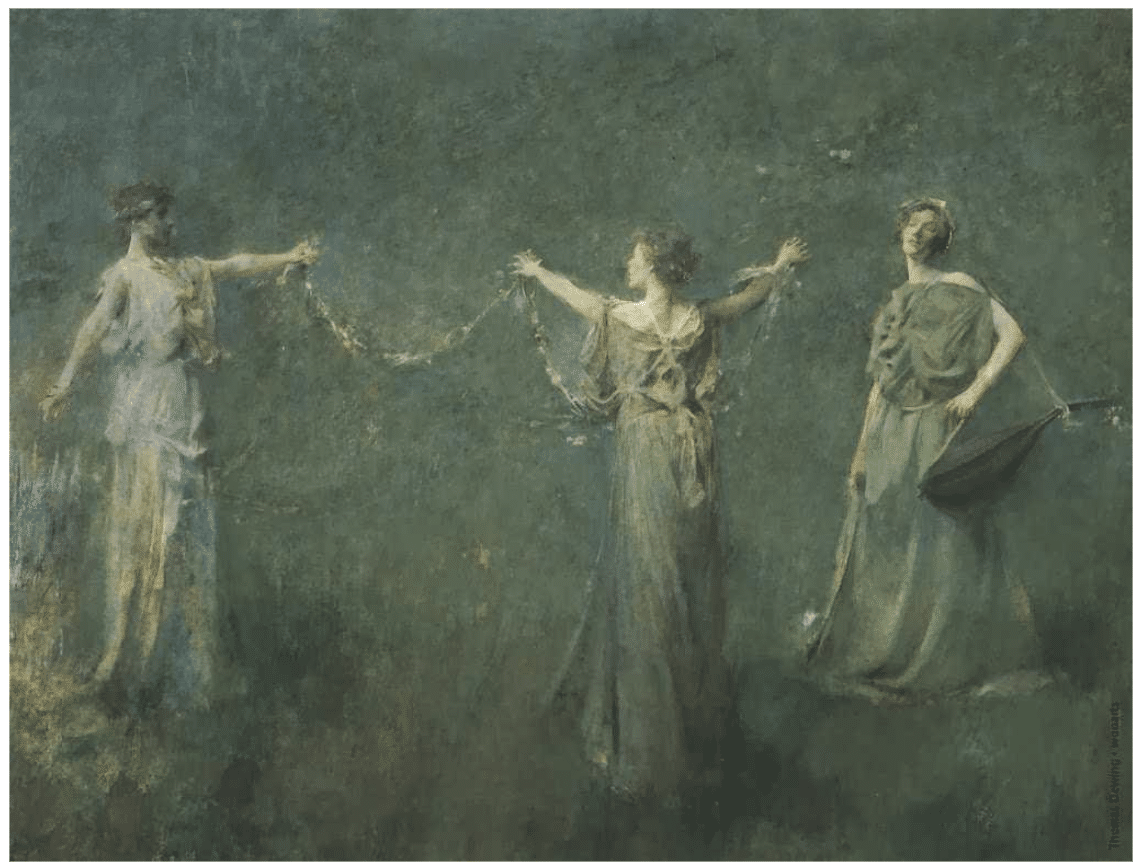

It wasn’t unusual for the time to find symbolic, classical-looking women standing in for things like “Spring,” “Prudence,” or “The Spirit of Music” in book illustrations, advertisements, murals and paintings. Dewing’s “The Days” 1886/87 is typical:

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, The Days, oil on canvas, 109.6 cm (43.1 in); width: 182.8 cm (71.9 in), between 1884 and 1886

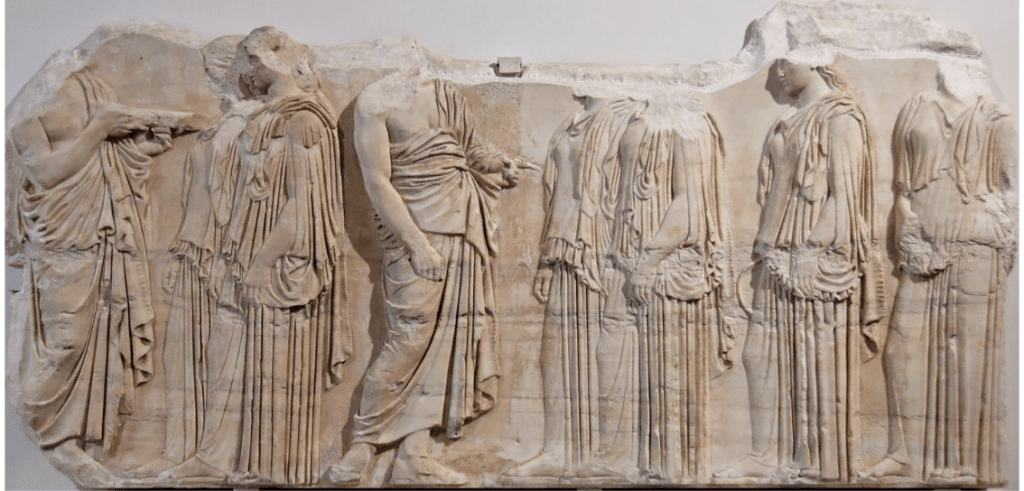

Here, in The Days, the figures wear classical togas and robes. They’re shown as if in sacred procession, lined up in a row (or “register”), as in a frieze, which is a horizontal decorative panel or band, usually sculpted, that often ran along the sides of Greek and Roman buildings, like the Parthenon.

Portion of the Parthenon frieze, Athens, c. 440 BC

Where Dewing departed from this precedent, he clothed his figures in elegant modern dresses, freed them from their strictly allegorical significance, and placed them in nebulous, atmospheric yet recognizably natural. The effect is to render an idyllic moment of waking life with the magic of memory and dreams.

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Summer, ca. 1890, oil on canvas, 42 1⁄8 x 54 1⁄4 in. (107.0 x 137.8 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of William T. Evans, 1909.7.21

He softened his forms into drifting and colliding shapes of ochre and mint green. His women don’t so much seem to be walking on the ground as much as arising from it like apparitions – or, indeed, embodiments of nature.

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, May (Welcome Sweet Springtime), c. 1890-1900, Oil on canvas 20 1/4 x 24 1/4 inches

Thomas Wilmer Dewing, After Sunset, oil, 106.8 x 137.6 cm (42 1/16 x 54 3/16 in) (1893) FREER GALLERY OF ART

Here in After Sunset, above, the beautiful figures (different from the pair in Before Sunrise) again don’t relate to each other, resonating with a sense of timelessness and mystery. There is something of the unknown in all these paintings. Though equally influenced by Whistler and Monet, Dewing painted his private world through the lens of his deepest imagination in a way unmistakably his own.