Passion and beauty intertwine in many ways throughout the history of Western art. At times the heart-melting effects of love take center stage, and a fleeting moment of human tenderness remains preserved for the ages in a timeless image.

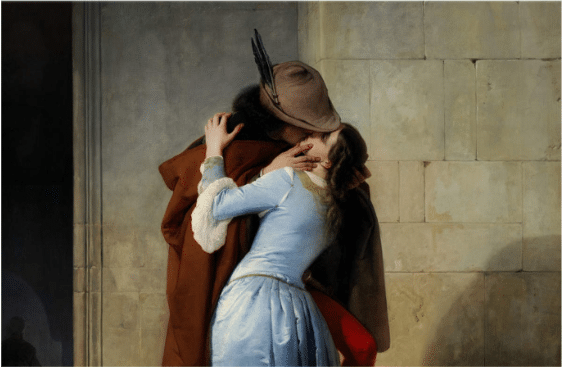

One of the most admired and passionate representations of a kiss in art history comes from Italian painter Francesco Hayez: She grips his shoulder to pull him close, he cradles her face in his hands – and yet, The Kiss (detail shown at top of page) has a wider social dimension as well. This painting was commissioned by Count Alfonso Maria Visconti of Saliceto and is loaded with symbolism expressing appreciation for the alliance between France and Italy that brought about the latter country’s unification.

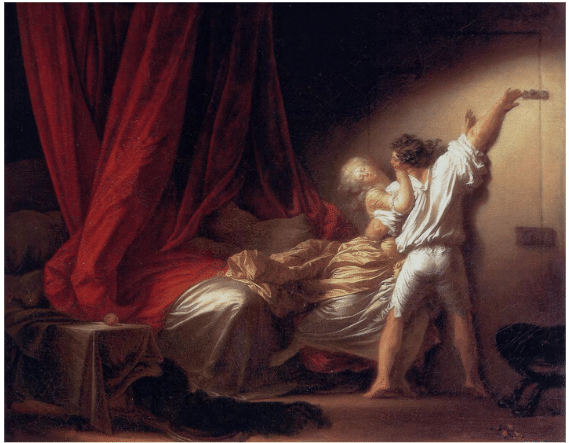

Another painting depicting lovers amid the swirl of world-changing political events comes from the French Rococo brush of Jean-Hororé Fragonnard, a society painter and an innovator in his own right during the heady years leading up to the French Revolution.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Bolt, oil, 73 cm × 93 cm (29 in × 37 in)

In Fragonard’s The Bolt, a half-dressed lover locks the door within a sumptuously draped boudoir, while his coy mistress, flowing silks melding with the rumpled bedsheets, at once surrenders bodily to him and pushes his lips away. Evocative of the libertine spirit of the 18th century, it reflects the state of mind, at least among the aristocratic class, of a free-wheeling period of privilege and excess.

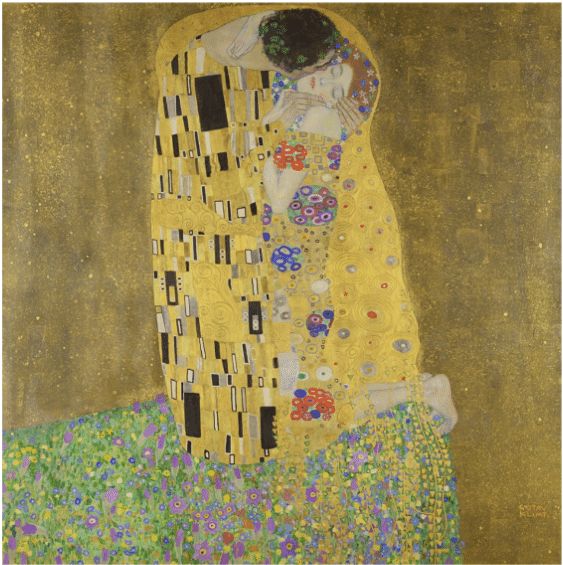

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, oil paint and gold leaf, 5′ 11″ x 5′ 11″ (1907-08)

The Kiss, the well-loved work by Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, depicts an embracing couple in a garden amid a magical shower of gold. Some art historians believe the couple portrayed here are Klimt himself and his long-time partner, Emilie Flöge. It’s a characteristic example of Klimt’s early 20th century “golden period,” during which he combined realism, sexuality, and decorative fantasy in oil paint and gold leaf.

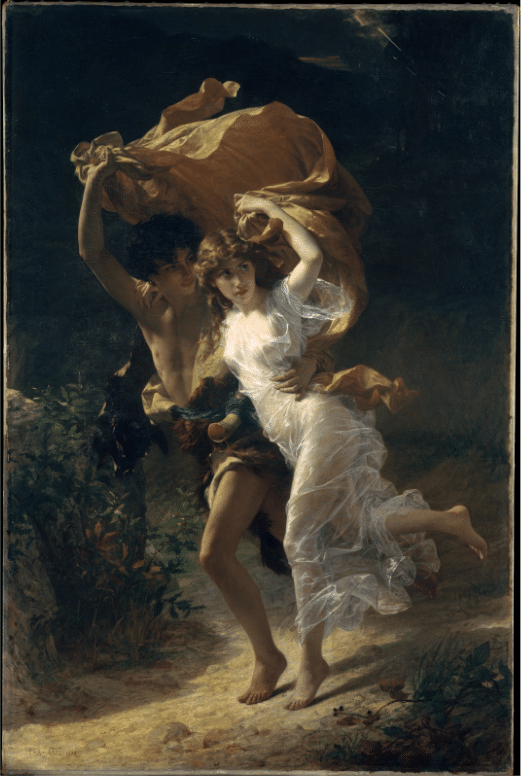

An earthier evocation of attraction turns up in Frenchman Auguste Cot’s The Storm (below). We know Cot’s lover is a shepherd from antiqutiy because he’s clothed in animal skins and carries a rough-hewn horn tied to his side. When shown at the Salon of 1880, some saw in it a reference to the romance Daphnis and Chloe by the ancient Greek writer Longus.

For this painting to fully reveal itself, you have to read the faces – while she glances fretfully behind her at the stormy sky, he is clearly more interested in her beauty, a gentle smile playing about his lips as he holds her, tenderly, assuring her she is safe. You can see it in person at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Sentimental? Of course. What is love anyway?

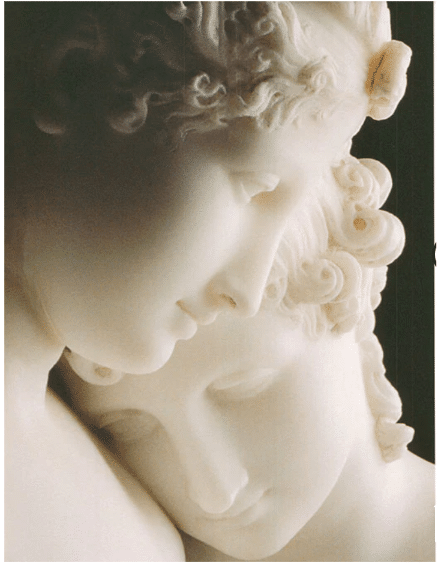

Fine, but what’s more romantic than a lover with wings? At once more chaste and more risqué, Antonio Canova’s Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, returns to the Neoclassicism that admired the simplicity, discipline, balance, and poise in the measured aesthetics of ancient Greece and Rome.

Antonio Canova, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, (first version 1787–1793), Louvre, Paris | Photo by Sara Darcaj on Unsplash

In this myth, Psyche falls into an infinite asleep, tricked by Aphrodite, who was angry at her for hurting her son Eros (aka the Roman Cupid). A recovered Eros awakens Psyche by his divine power, in this case represented by his kiss.

Many artists treated this motif, and Canova did so several times.

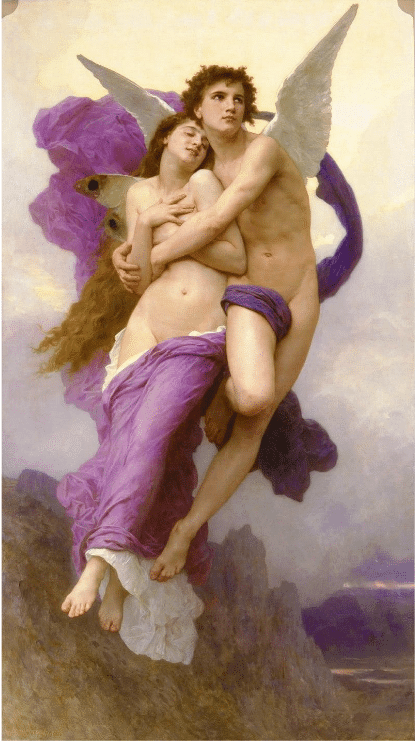

Some hundred years later, the classical tales of love among mortals and gods were still being told, as we see in the 19th century Academic art of Adolphe Bouguereau, who exhibited his own version of the Cupid and Psyche myth in the Paris Salon of 1895. (In fact, the classical tales are still being told, though they have new names, such as “Sleeping Beauty,” of course.)

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, The abduction of Psyche 1895.

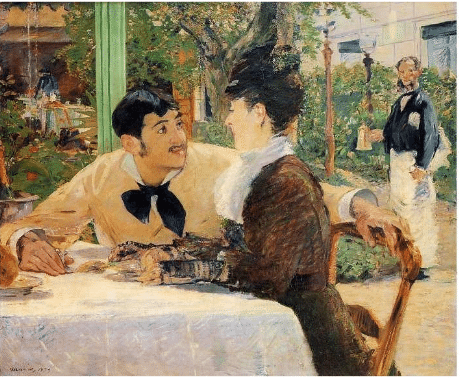

Now compare all that fuss and fancy with Manet’s realism. In Chez le Père Lathuille (below), he invites us into a modern restaurant garden on a summer day in Paris, where a young man gazes into a woman’s eyes. A waiter in the background looks on, seeming all the more solitary, stiffly frozen as he gazes across at the dreamy young couple.

Édouard Manet, Chez le Père Lathuille, 1879

Finally, no sampling of romantic lovers in art would be complete without Auguste Rodin’s (1840–1917), The Kiss. With its naturalistic, passionate figures spiraling about each other as they emerge from the earthy stone, it is a true monument to romantic love.

Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, 1898, plaster copy of the 1882 bronze