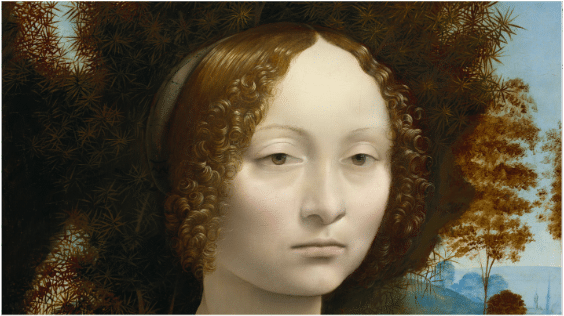

Ginevra de’ Benci is the only painting by Leonardo da Vinci in North or South America. It’s a small portrait (it was once a larger one though), painted when Leonardo was still in his early twenties (c. 1475).

Mona Lisa wouldn’t crash the party for some 30 years later, but if not for Leonardo’s innovations while painting Ginerva, she probably would have looked very different when she did.

Ginevra is one of the first works Leonardo made with oil paint, then a new medium taking the rest of Europe by storm. Unlike egg tempera, which is opaque and unforgiving, the slower drying time and lustrous quality of oil paint allowed for far more nuance, texture, and depth, especially because it could be applied in thin layers (or “glazes” of semi-transparent paint). Leonardo’s famous sfumato (“smoky”) technique leaned into oil’s potential to realistically capture the shadows on skin and the haze of a distant landscape.

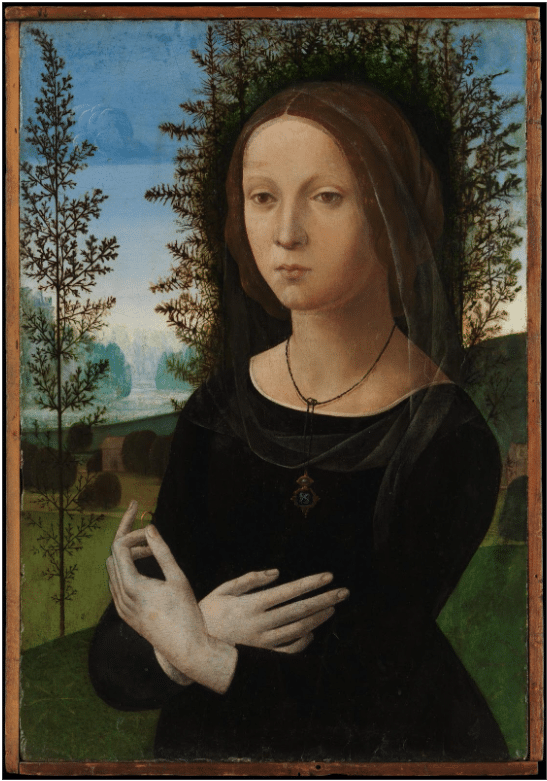

Compare this conventional Renaissance portrait by Ercole de’ Roberti, Ginevra Bentivoglio, c. 1474/1477, tempera on poplar panel, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.220

Leonardo applied the same naturalism to Ginevra herself. Rather than outlining her features, he paints how light reflects off her skin. You can see this in the depth and subtlety in the shadows under her chin.

In another important innovation, the artist painted Ginervra in what’s known as three-quarter pose, facing the viewer, shoulders turned to the side. This pose is standard procedure now, but only thanks to Leonardo; at the time, portraitists posed their subjects in profile.

Who Was Ginervra … and Where is the Rest of Her?

Ginevra de’ Benci was the daughter of a Florentine banker. Because of her family’s wealth and class, Ginevra was permitted an education. She was known as a poet and good conversationalist. Her intelligence and beauty caught the attention of many men who wrote poems dedicated to her. Artists competed for the privilege of painting her. It’s believed Leonardo did so on commission from a wealthy patron.

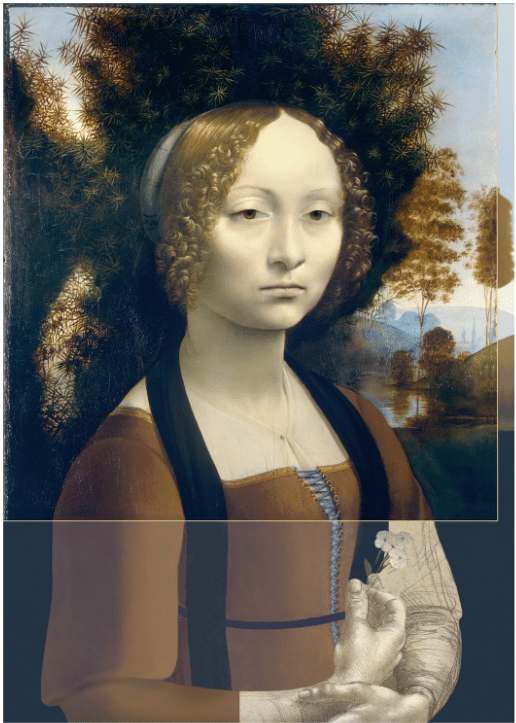

A reconstruction of how Leonardo da Vinci’sGinevra de’ Benci may have originally looked.

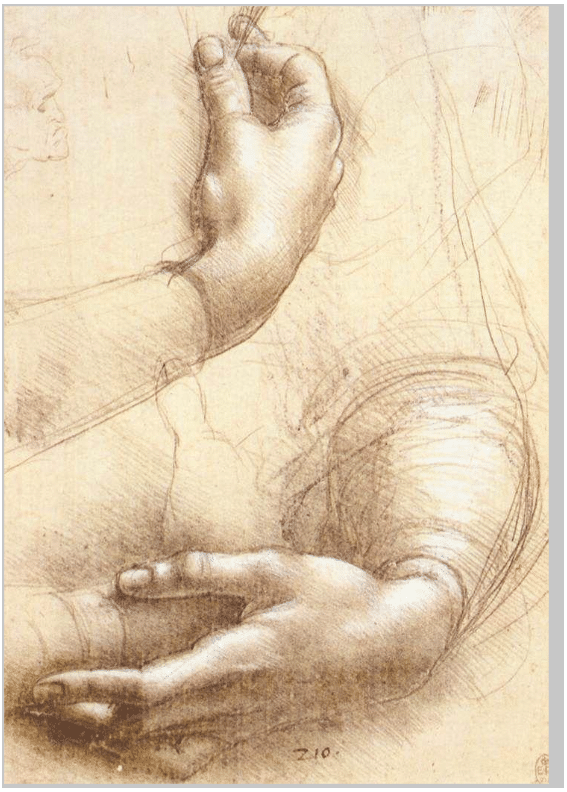

The Ginervra portrait as we see it today is only part of the original work. For some unknown reason, the original panel was cut down along the way. There’s a beautiful drawing by Leonardo done the same year as the painting that suggests that he painted Ginevra’s hands cradled at her waist.

Leonardo da Vinci, Study of Hands, 1474. Silverpoint and white highlights on pink prepared paper. 8.43 x 5.91 in. Royal Library, Windsor, UK. Wikimedia Commons

There’s clincher though is a copy-cat painting of Ginervra created about 20 years later, with the sitter’s hands in that position.

An inscription on the back of this portrait by Lorenzo di Credi identifies the subject as “Ginevra d’Amerigo de Benci.” The painting was likely inspired by Leonardo’s portrait of Ginevra. Lorenzo di Credi, Portrait of a Young Woman, oil on wood, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

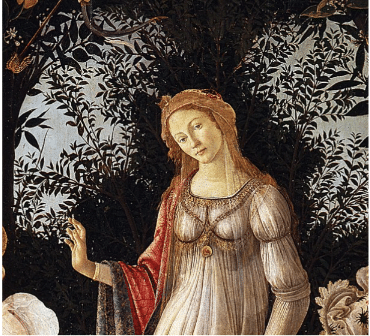

The branches framing her head, by the way, are juniper, a play-on-words on Ginervra’s name (juniper is ginevro in old Italian). Botticelli used a similar “halo of branches” motif for his Primavera.

Botticelli, Primavera (detail), c 1480s.

Leonardo’s Ginevra, with her face turned toward the viewer so that we can see her expression, ushered in a new epoch in portrait painting that’s given us the genre as it’s still practiced today. It also helped define the Italian Renaissance; Leonardo’s revolutionary work, here and elsewhere, was the result of an inquisitive mind, eager to learn the secrets of humanity inside and out. We have him to thank for helping us along the way to using oil paint to explore human psychology in art.

Joshua Larock teaches the art of the “old master” portrait in oils in his video Classical Portraits.