It is a puzzlement: the larger your painting is, the more concentrated you feel you have to work. That’s because a patch of blue sky in a 40” x 36” landscape feels a lot emptier (and larger – because it is!) than a proportionately sized patch of blue sky in an 8” x 10.”

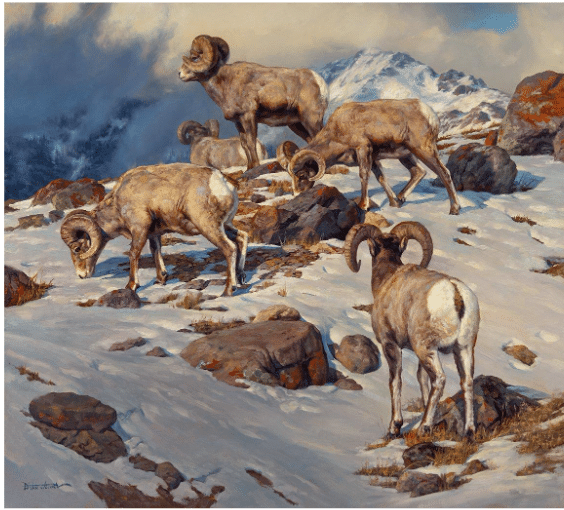

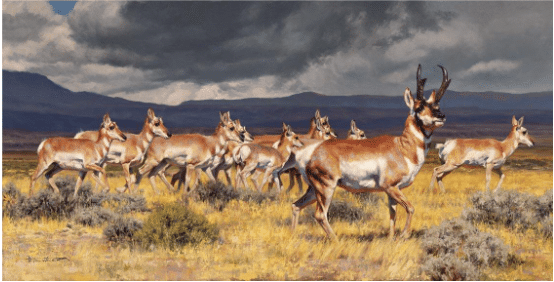

“Every inch of your painting should have interest,” says this maxim. By “interest” is meant something happening – some kind of variety – a minute detail works, as in Dustin Van Wechel’s masterful wildlife paintings).

But really it could be anything that works. It could be a swirl of unmixed color, a bump or two of impasto paint, a barely perceptible streak, line, film, or dot, an intriguing texture, a visible brushstroke. I know a painter who finds a dead spot in his landscapes and flicks in a little dot of Cadmium Red. If anybody asks, he just tells them it’s a dumpster. Obviously, that’s not going to work for everybody!

The main point is – avoid dead spots. But even if you don’t take it literally and treat “keep interest everywhere” as a hard and fast rule, keeping it in the back of your mind can help keep things … well, interesting.

Dustin Van Wechel, Speed Dating, oil, 24” x 48.”

This isn’t an injunction to make busy paintings; the eye does need places to rest. It is entirely possible to use softer lines and less contrasting values to achieve this, as I’d argue Dustin Van Wechel does in his painting whimsically titled Speed Dating (above). I’d say that’s an exciting, not a busy, painting, and there isn’t a half-inch in it where nothing is happening. Instead it’s full of vitality, focus and precision, and it’s anything but dull.

Or take The Hopeless Suitor (below) and apply the “sky patch” example from above – look how the grass shadows are broken up with delicate touches of detail at just the right value. Those could have been dead spots, but the artist didn’t let that happen. They could also have been distracting – that didn’t happen either.

Dustin Van Wechel, The Hopeless Suitor, oil, 24” x 30”

Again, it’s a fine line between a busy painting and one in which every nook and cranny holds something of interest for the viewer. Much of it has to do with modulated values and chroma (you can think of “chroma” as the intensity or purity vs. the “grayness” of a color). When done right, the result is a stunning painting.

Dustin Van Wechel has a teaching DVD you might be interested in called Painting Wildlife and Waterfowl.

Bringing the Gods and Goddesses Down to Earth

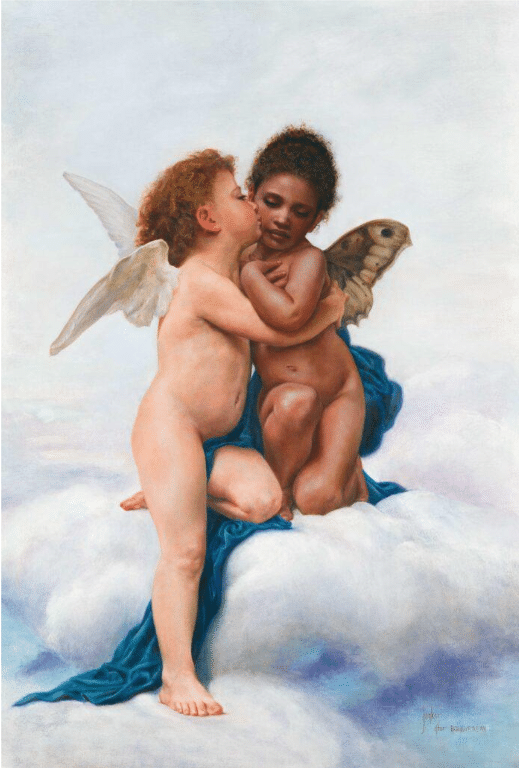

Julianne Jonker, Cupid and Psyche, 2022, cold wax and oil on raised birch panel, 36 x 24 in., available through the artist.

Last week we ran an article for Valentine’s Day that included several artists’ takes on the classical Cupid and Psyche myth. This article by Allison Malafronte shines light on a gifted individual who’s updated Bouguereau’s version.

Julianne Jonker (b. 1957) was primed from a young age to become the innovative painter, sculptor, and photographer she is today, as she grew up in a family of jazz musicians and creatives who encouraged experimentation, improvisation, and sensitive interpretation. She pursued both classical and contemporary training — first at the Minnesota River School of Fine Art and then with several professional artists in the U.S. and Europe — and today she combines many different disciplines and styles with her own creativity to best honor the subject she is capturing.

“My intention for my art is to serve as a conduit, a visual language for our ability to see and be seen,” the Minnesota-based artist says. “I hope to impart to the work the same beauty I catch a glimpse of when I view a scene or an individual.”

Currently, Jonker is making her works with encaustic, cold wax, and oil paints. This combination of materials allows her to achieve a sculptural quality, creating depth and texture while providing a soft matte patina. “Combining classical and contemporary styles, I use these materials to capture the nuances of each subject’s likeness,” she says.

“Working in a rhythm layer by layer, wax and oil combined, I build then excavate, create then destroy, using an array of tools to evoke the history and depth that defines the texture of wax paintings.”

Jonker’s series, Gods and Goddesses, began during the pandemic, when the artist was deep in introspection considering how to bridge the disconnect and invisibility people experienced during that prolonged period of isolation. Within that collection is her reinterpretation of Bouguereau’s masterpiece “Cupid and Psyche” (1889), seen through a new lens of inclusion.

“The original painting had two little pink cherubs, probably taken from French models since Bouguereau was French,” the artist explains. “My granddaughters and other little people of color rarely see themselves depicted as cherubs, princesses, heroes, or in this case a butterfly/moth. It’s so important for all children to see their own reflection in the real world around them, as well as in art and media.”

Jonker continues, “I created the little moth/cherub out of my imagination. She represents many ethnicities of brown-skinned little girls. The moth’s symbolic meaning is resurrection and transformation. A moth represents tremendous change, but it also seeks the light. Thus, the spiritual meaning is to trust the changes that are happening, and that freedom and liberation are right around the corner.”

Connect with the artist: www.juliannejonker.com

This article was originally published in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine (subscribe here).