Sanford Robinson Gifford’s panoramic Maine landscape above partakes of the Hudson River tendency to render the American landscape in majesty and grandeur. But Gifford liked to play around with scale, and it appears, upon close inspection, that he decided to have a little extra fun with this one.

The painting depicts Gifford himself in the act of painting the landscape. We know this because he titled it “The Artist Sketching” (not “An Artist Sketching”). That isn’t unusual, it’s something many painters have done. But there’s something else going on that you might not notice at first.

DETAIL, Sanford Robinson Gifford, “The Artist Sketching at Mount Desert Island, Maine” showing the painting inside the paint box.

If you peek inside the lid of the artist’s (Gifford’s) “pochade,” or sketching box, you can just make out a completed sketch that looks awfully like the very painting we’re viewing – the one called “The Artist Sketching at Mount Desert Island, Maine.” So this isn’t only a painting within a painting – it’s the same painting within the same painting!

That means there’s going to be another tiny version of this same painting on the tiny pochade-box lid in the next tiny painting too! And of course, there’s going to be, in ever tinier iterations, painting after painting of a man next to a painting of the same man painting next to a painting of the same man painting next to a painting of the same man painting next to a painting… you get the idea.

But wait! The original painting shows Gifford sketching. What if he’s sketching out ANOTHER VERSION of the same painting we’re looking at? That would mean the craziness stretches to infinity in not just one but in two directions – into the future as well as the past! So then this would be a painting of a man actively making another version of the same painting of a man sitting next to a finished painting of a man who’s actively making another version of the same painting of a man sitting next to a finished painting of a man … (this way madness lies!)

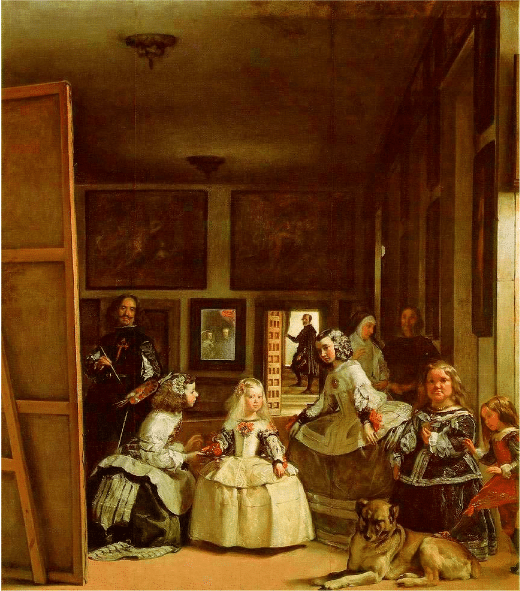

This kind of self-reflectivity of the “endlessly recursive” image or “Drode Effect” as it’s called can make your head spin. Something different but no less complex appears in the famous Las Meninas or Maids of Honor by “Old Master” Spanish realist Diego Velasquez.

Diego Velasquez, Las Meninas, oil on canvas, 1645.

Commissioned by the king of Spain, Las Maninas shows us “the Infanta,” young Princess Margarita in the center, surrounded by her maids of honor and several other figures from the royal court. We know the identity of everyone else in the picture too, and that is Velasquez at the easel squeezed, as would be proper for a mere artisan of the king, into the shadows off to the left. Antonio Palomino, the first to write about Las Meninas made this clear when he said, “… the name of Velasquez will live from century to century as long as that of the most excellent and beautiful Margarita, in whose shadow his image is immortalized.”

And that has a lot to do with why he painted himself painting. Through the presence of the princess, king and queen, the canvas commemorates Velasquez’s own position as royal painter and, emphasized by his slyly painting himself taller than all the other figures in the painting, painting the ACT of painting in the presence of royalty makes a claim not only for him but for the nobility of the art.

Notice that red cross he wears? It has to do with his lifelong aspiration to the ancient knighthood of the Order of Santiago. This was a papal military order to which only the wealthiest nobility and aristocrats aspired, to which one was finally admitted, with great difficulty, at the end of one’s life. We do know that the cross was added later – it’s said, by King Philip himself, after his beloved friend’s death.

Into the House of Mirrors

But wait, there’s more! Computer imaging of the space of Velasquez’s painting as created by the perspective reveals that the vanishing point is neither the princess nor the mirror – but the doorway next to it, in which a courtier parts a curtain. The reflection in the mirror is actually aligned precisely with what is on the canvas that Velasquez is painting – and not with the viewer.

Therefore, the princess and her maids are the audience for a painting within the painting, one that we never get to see, a portrait of the king and queen. We are viewing a painting of the princes and her maids watching Velasquez paint the portrait of the king and queen of Spain, and we are viewing the scene from the royal couple’s point of view. So ion a way Velasquez has painted us his painting’s viewers, because it’s what we would be seeing as the painting’s subject.

Do you know of any other paintings of painters painting themselves painting themselves or painting us looking at painters painting themselves? (Hahah.) Send them along so we can keep losing brain cells trying to keep up and keep track of all this nonsense, okay?

The representation of the human figure remains arguably the core of contemporary realist painting. If you’re ready to delve into the techniques of classical portraiture, you might want to check out this video by.

If landscape is more your thing, and you like the Hudson River School style, then Erik Koepel has you covered. Check out his deep-dive videos here.