Last week we looked at a number of paintings in which artist painted themselves painting themselves.

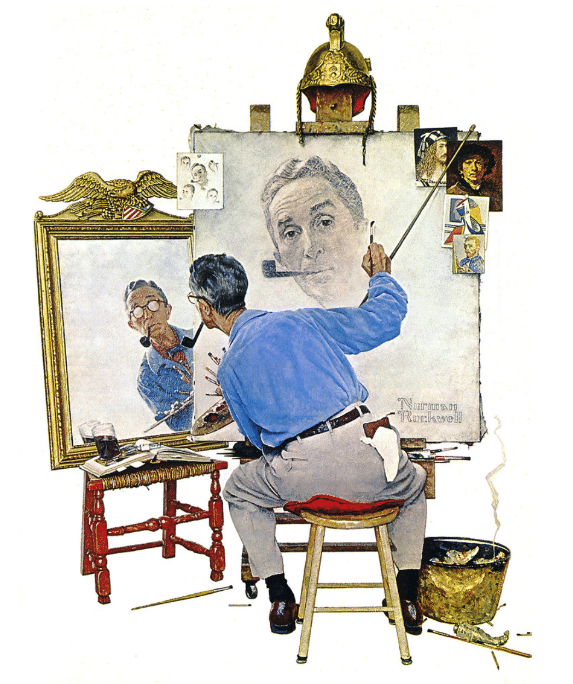

Several of you wrote in to call my attention to a classic I’d forgotten about – Norman Rockwell’s Triple Self Portrait of 1960. This is a wonderful painting full of nuance, multiple inside art history jokes, and self-deprecating humor.

The heart of Rockwell’s painting is in how little the painting resembles the artist. As we can see in the mirror, the real Norman Rockwell presents as a puzzled and bespectacled fellow with a drooping pipe. The portrait, however, gives us a new and improved Norman, with handsome features, suavely arched eyebrows, and a spry and confident, self-satisfied demeaner. So the artist has used a measure of “poetic license” to “enhance” his image, and we as the audience of course smile along with him – it’s relatable, humanizing, and endearing.

Ranged around his workspace are references to art history and the grand Old Master tradition of portraiture. There’s an open art book in front of him and attached directly to the paper he’s working on (not even just on the easel) are self-portraits by the greats, including Rembrandt and van Gogh. There’s also a postcard of a Modernist painting, just to demonstrate that the artist is well-aware of the current trend toward abstract art (this was 1960) and is making a conscious choice not to follow it.

The Roman gladiator’s helmet atop the easel is another tongue-in-cheek reference to Art with a capital A – it was common among Dutch “golden age” masters and other post-Renaissance European portraitists to dress their models in the costumes of historical types and illustrious figures (see the props scattered around the studio in the de Heem painting of Interior of a Painter’s Studio below). There’s a subtle irony then in how the gleaming helmet – this symbol of classical manhood and victory – hovers over the artist’s mild-mannered likeness as he works.

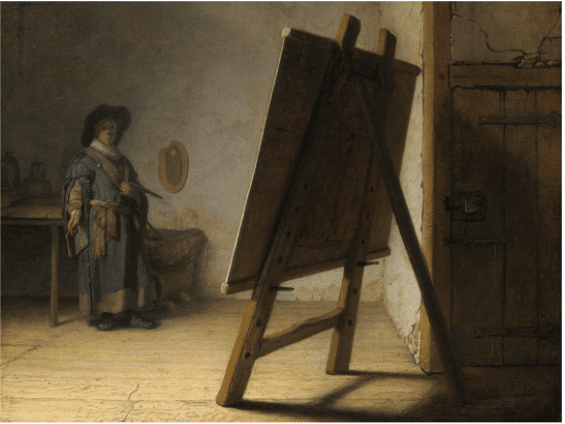

Speaking of Rembrandt, few artists of earlier days produced as many self-portraits. We can all picture at least one, right? There are a number in which he explicitly links himself to the practice of painting of course, but there’s only one I’m aware of in which he actually paints himself in the act of painting.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, Artist in His Studio, about 1628.

More accurately, in Artist in His Studio, Rembrandt paints himself in the act of pausing while painting. The artist has stepped back from his canvas to assess, his brush hand poised, held out from his side. The implication is that painting is not just a matter of workmanship or artisan craft (as many considered it then); rather, artistic endeavor requires thought, critical judgment, and a special kind of reason capable of reading and assessing effective images.

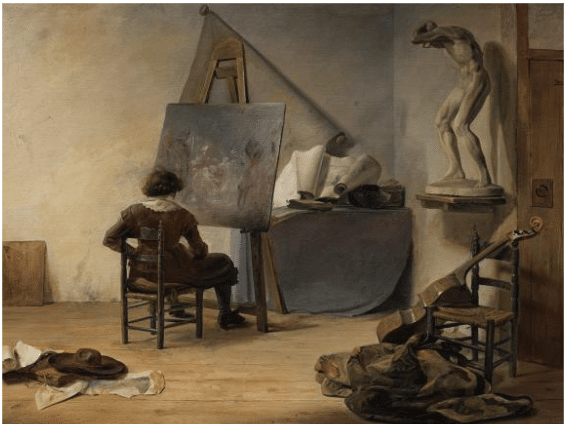

Jan Davidsz de Heem, Interior of a Painter’s Studio, Oil on panel, 58 × 81 cm (22 13/16 × 31 7/8 in.) Museum of Fine Arts. Gift of Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo, in support of the Center for Netherlandish Art. About 1630.

This next depiction (above) of a solitary painter seems to be Jan Davidsz de Heem’s response, two years later, to Rembrandt’s Artist in His Studio. De Heem and Rembrandt both worked in the university town of Leiden before Rembrandt left for Amsterdam in 1631.

Unlike Rembrandt’s barren studio, De Heem’s space is filled with various props: a volume of prints on the table, a viola da gamba, an oak panel leaning against the wall, and a plaster cast of a Michelangelesque statue. Rather than focusing on the thought process before beginning to paint (or pausing mid-painting to assess), De Heem highlights the equal challenge of sketching out a composition.

When White Umbrellas Dotted the Meadows

Here’s one more example, this time from the breezy heights of New Hampshire’s White Mountains An artist who witnessed the blossoming of the American landscape tradition, painter Benjamin Champney wrote this in his memoirs: “Thus every year brought fresh visitors to North Conway as the news of its attractions spread, until in 1853 and 1854 the meadows and the banks of the Saco were dotted all about with white umbrellas in great numbers.”

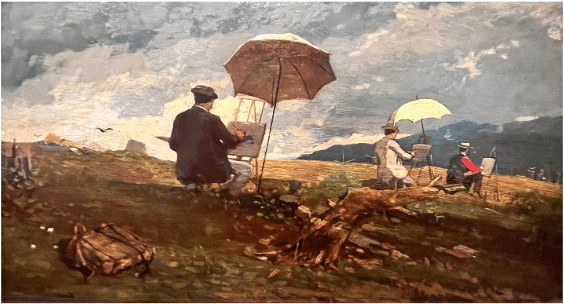

Winslow Homer, Artists Sketching in the White Mountains, oil on panel, 1868

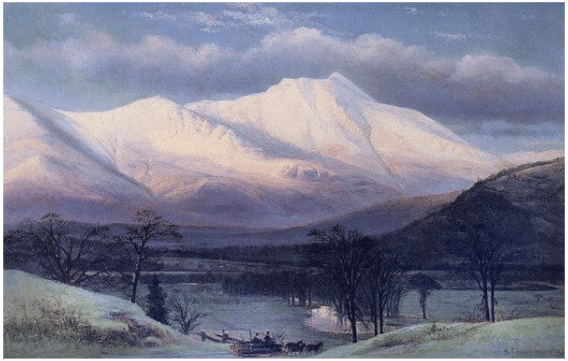

Those umbrellas springing up like daisies marked the mid-century wave of American landscape painters working in the footsteps of Thomas Cole and the Hudson River School of painters. Beyond the Catskills and the Hudson River Valley, they came to New Hampshire in search of a wilder nature, with loftier mountains and stormier skies. They found a perfect blend of the picturesque and the sublime – beautiful fields, meadows, and rivers, and towering mountains of forbidding snow, ice, and rock – in the northern Presidential Range.

Benjamin Champney, Moat Mountain from North Conway, Oil on canvas, 18 x 28 inches

And they kept coming! Winslow Homer’s “white umbrellas” representation is dated 1868. They weren’t plein air painters though – they were sketching, as Champney says. They were painting small (i.e. portable) studies of mountains, trees, and bits of sublime scenery to use later in their studios. Back in places like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, or Providence, RI, they’d assemble their sketches into the larger, full-sized paintings (in keeping with pre-Impressionist art history in Europe) that the American market had come to expect.

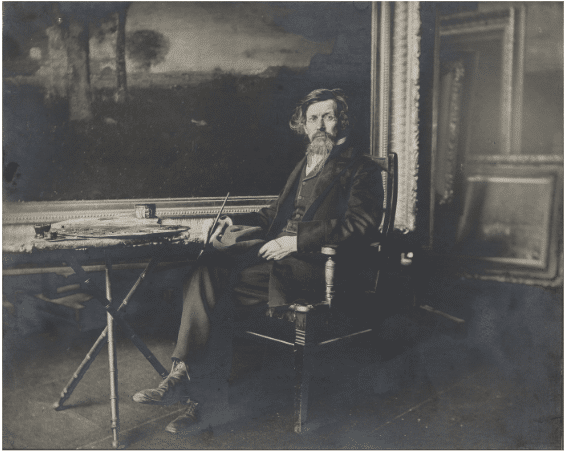

Photo of George Inness seated in his New Jersey studio, 1890, with a typically large landscape behind him. Inness blended aspects of Hudson River School painting with innovations in Europe to channel his vision into outstanding and highly original work.

That painting above by Winslow Homer (Artists Sketching in the White Mountains) is on display in the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, near Prouts Neck, Scarborough, ME, where Homer spent the last years of his life. He was working as an illustrator then, and he was in the White Mountains to document their popularity with artists and tourists alike.

In Homer’s painting, three artists perch beside their easels along a high sloping field, creating a strong diagonal across the composition. Homer uses it to emphasize the mountainous slope, giving us his sense of civilization and sophistication coming directly into contact with wild nature. The two right-hand figures are thought to be Homer’s companions and fellow painters Homer Dodge Martin and John Fitch.

Says the museum: “The closest man, cast in shadow, is perhaps Homer himself; his signature is visible atop the knapsack just behind him.”

We’re present, then, at another painting of an artist painting himself painting. Will he be painting in the two friends in front of that blue mountain he’s got going? And eventually adding himself painting the same painting ?…. and thus, painting himself painting himself painting himself painting himself…. To Infinity??!!!

We’ll have to leave it at that for now.

If the venerable genre of self-portraiture is your thing, there’s a wealth of videos on the subject here.

And if Rembrandt is calling you, there’s no surprise. 350 years after Rembrandt’s death, artists from around the globe continue to chase the dream of painting like the Master. Whether it’s students seeking to copy Rembrandt’s work as part of their studies or high-level professional artists wishing to apply the centuries-old techniques to their already polished work, painting in the manner of Rembrandt represents an ultimate achievement. If that’s your interested, there’s a video here where you can learn all about it.