“Dry and thirsty, a paintbrush pokes its nose into water, then ground inkstone, and swells with the abundance of expressive potential.” So begins a lively essay on contemporary Chinese painter the late Wu Guanzhong written by Shauna Laurel Jones and published in the current issue of the magazine Orion.

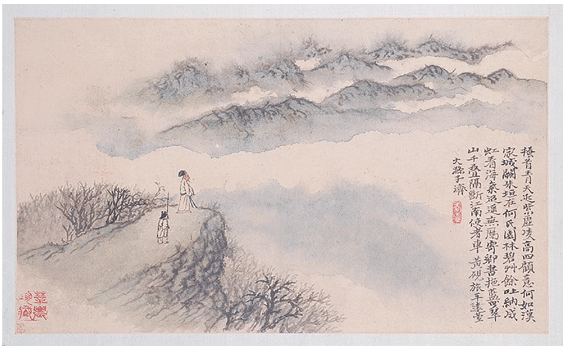

“Ink wash on paper is ancient, basic, and incredibly demanding,” she notes. “The mark that is made is the mark that will stay.” The ink-wash artist doesn’t copy nature but almost becomes nature, or at least one with it. The goal is to get past the ego and paint in a meditative, near-mystical mindset with, or “as” nature. The artist must act in the moment, without miscalculation, the brushstrokes full of dynamic energy and the whole composition organic, evocative, alive.

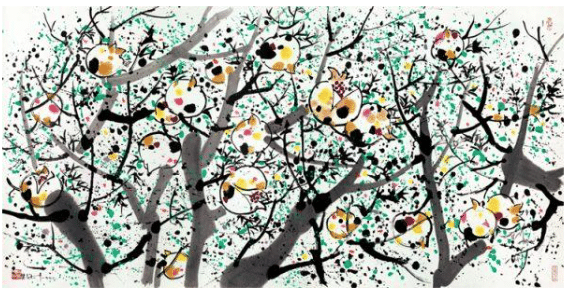

Wu Guanzhong, ‘Pomegranate’, Ink & Color on Paper

Nature and mind met in the paintings of Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010) with an updated modern sensibility. In the 1970s, he brought Western influences into the ancient Eastern ink-on-paper tradition and still felt free to move back and forth fluidly between old and new styles, mediums, and techniques.

“I used eastern rhythms in the absorption of western form and color, like a snake swallowing an elephant,” he said. “Oil paint and ink are two blades of the same pair of scissors used to cut the pattern for a whole new suit. To nationalize oil painting and to modernize Chinese painting: in my view these are two sides of the same face.” Wu explored a full array of mediums in fact.

Wu Guanzhong, Growth, 80.5 x 95.5 cm , Lithography

Wu applied the principles of traditional Chinese painting, including the simplification and expression of essence over realism, using the visual language of modernism and abstraction. Among the results were remarkable semi-abstract landscapes created in a state of lively intuitive sympathy with the artist’s experience of nature.

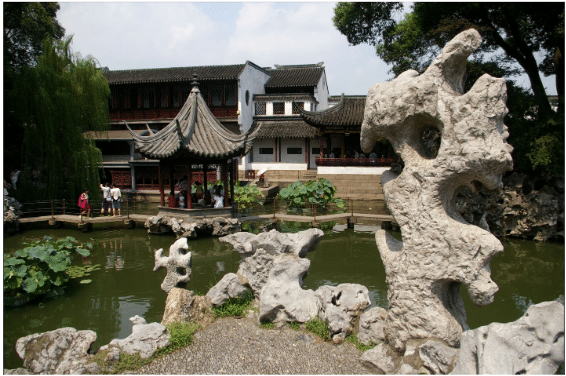

Among his most well-known works is a series of paintings he completed of Lion Grove Garden, one of China’s largest and oldest “rockeries.” Begun by a Buddhist monk in 1342, the name of the garden is derived from the lion-shaped taihu rocks, which in turn were built as a reference to the symbolic lion in a Buddhist text titled the Lion’s Roar Sutra. Guanzhong’s brush painting (below) depicts the rocks, trees and pagoda structure at the garden’s heart as he saw it – as something like an energetic jigsaw puzzle made up of the site’s singular lines and forms.

Wu Guanzhong, Lion Grove Garden, ink and color on paper, with two seals of the artist, 69.5 x 94.2 cm 27⅜ x 37⅛ in.

Lion Grove Garden in Suzhou, Jakub Hałun showing a few of the rocks some ways away from the labyrinth-like “forest” of them at the heart of the garden that Wu Guanzhong painted. Creative Commons (Wikimedia)

The son of a village schoolteacher, he studied initially at the National Academy of Art in Hangzhou then moved to Paris in 1947, where he was particularly drawn to the work of the post-Impressionists (particularly Pisarro, Cezanne and Van Gogh). Following his return to China in 1950, however, he found himself out of step artistically and politically, the Communist authorities favoring a Social Realist style that featured heroic workers, farmers and soldiers.

In 1966, at the start of the Cultural Revolution, Wu destroyed many of his oil paintings, for fear of what the Red Guards would make of them if they searched his house. He was right to be fearful: Wu was summarily banned from painting for seven years; denounced as a ‘bourgeois formalist’; and banished from Beijing to the remote countryside to perform manual labor (far from his wife and family).

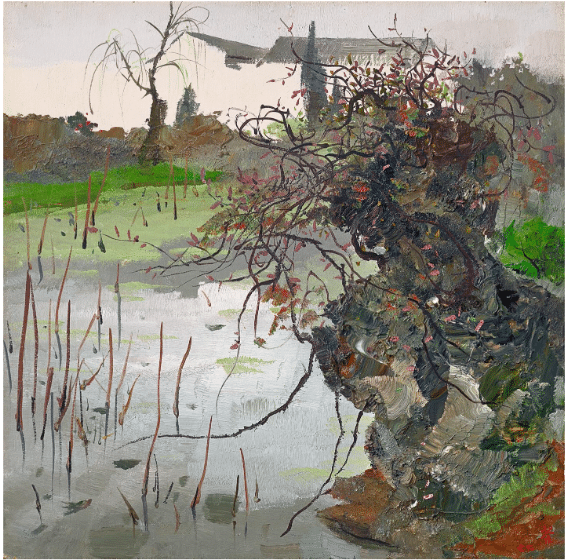

Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), A Corner of a Garden (By the Lake), 1977. Oil on board. 45.4 x 45.4 cm (17⅞ x 17⅞ in). Sold for HK$14,895,000 on 28 May 2023 at Christie’s in Hong Kong

It’s often said that Wu combined a sense of color and composition from Western oil painting with a spirit, lightness of touch and tonal variation of Chinese ink-wash painting.

“The goal of painting-Ch’an was to let the energy that animates the tree and the river also guide your brush,” Hinton has said in interviews. “Wu-wei, which literally means “not acting,” was an ideal state. It doesn’t refer to doing nothing; it refers to leaving behind that alienated, calculating version of yourself. When that happens—when a painter successfully integrates himself with the cosmos—it’s as though the power that uplifted the real mountains (or trees, or stones) is at work on the paper.”

Wu Guanshong, Pines, ink and color on rice paper, 140 x 179 cm, (1995) Shanghai Art Museum.

For Wu technique was “just technique,” he suggested; it isn’t the tool but what you channel into that counts. “Brush and ink are only servants of thoughts and emotions,” he said. “They should follow your emotion and change with the emotion.”

“Brush-and-ink is a technique. Brushwork is embodied within technique, technique is not embodied within brushwork, and technique is only a means that serves the artist in the expression of his emotions.”

Just as for the traditional Chinese landscape painters the preceded him, nature and his relationship to it were first and last. “Whenever I am at an impasse, I turn to natural scenery,” he said. “In nature I can reveal my true feelings to the mountains and rivers: my depth of feelings toward the motherland and my love toward my people. I set off from my own native village and Lu Xun’s native soil.” (Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, lived in southern China’s Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, a place of childhood memories and lifelong attachment for the painter, for whom Xun was a guiding light.)

‘With Wu, there’s this wonderful sense of countless different elements making up the whole,’ Christie’s art historian Eric Chang says, ‘and that if you removed just one of those elements, even the tiniest, the picture would fall apart.”

“His paintings capture an experience more than a sight,” Chang says. “They’re the sort of images you think you can enter… Wu was an artist of feeling rather than fact.”

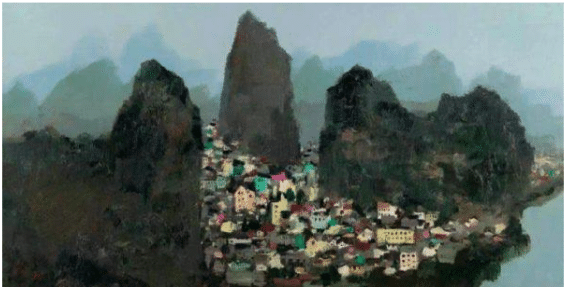

Guilin, 43 x 88 cm, Oil on Wooden Panel (1970)

Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), Woods and a Spring. Scroll, mounted and framed, ink and colour on paper. 136.3 x 67.3 cm (53⅜ x 26½ in). Sold for HK$14,895,000 on 31 May 2023 at Christie’s in Hong Kong

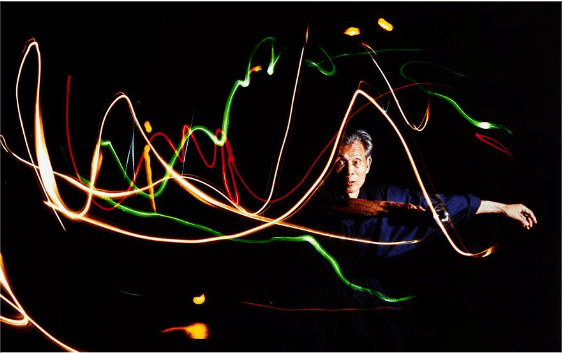

Wu Guanzhong at his exhibition Light within Ink at The Arts House in Singapore, 1988. Photo: Chua Soo Bin

Contemporary artist Chien Chung-Wei is the first artist in Taiwan to become a Signature member of the American Watercolor Society and the National Watercolor Society. He’s also the author of the bestselling books The Intrigue of Form and Learning Watercolor from Demonstrations.

Artists and collectors say the watercolor works of Chien Chung-Wei appear to embrace the spirits and temperament of Western watercolor masters over the last two centuries. Check out his video here.