Writer Matt Cardin calls it “creativity’s hidden paradox,” and it goes like this: “What is most private and personal in you is also what is most universal.” He means that what is deep in you is deep in all people and in the world itself. “The deeper you look into yourself,” he says, “the more you find what is most important to everyone.”

“This is the source and essence of creativity on the part of both creator and the audience,” Cardin says. “It’s also the meaning of spirituality and religion.”

Most artists, consciously or not, believe something along those lines – they trust it’s possible for art to communicate important truths, even (maybe especially) things that cannot be put into words. They trust that, even if you can’t verbalize what a given work of art is “about,” anyone willing to invest a certain amount of time and emotional energy can feel and understand it themselves. Again, the creative paradox: Artists make work for themselves but they make it for others at the same time.

Nineteenth-century American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson put it this way: “Trust thyself; every heart vibrates to that iron string.” Be the cello that resonates with the bow string, on which the unseen (emotion, truth, beauty) plays itself into existence. “Speak your latent (your most personal and deepest) conviction, and it shall be the universal sense; for the inmost in due time becomes the outmost.”

Of course, artists are largely “visual people” and therefore dislike talking about their work and what it means. It’s not literally about “speaking” your truth; it comes down to first learning your craft and then “trusting your instinct,” maybe they’ll say. But it’s doing art and artists a disservice to always only be talking about technique, when after all it’s what an artist puts of themselves into the work that counts.

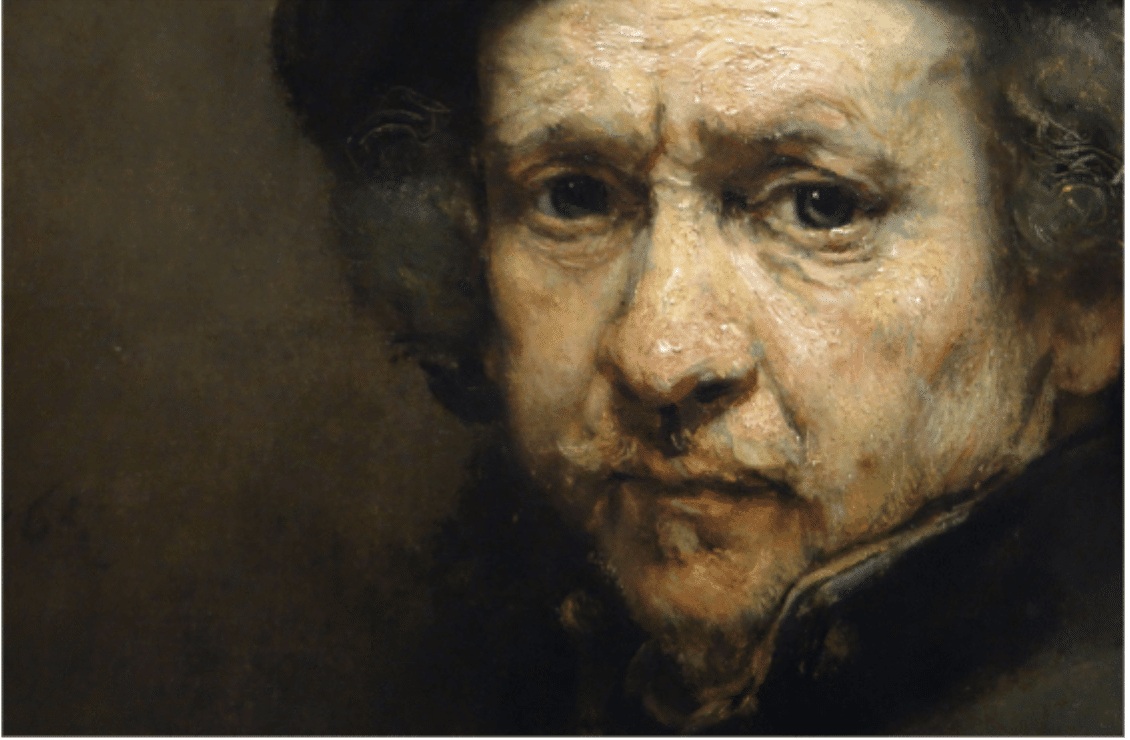

We’d do well to remind ourselves that we’re all part of the same human family, always and forever. Otherwise, how on earth can a cave painting made in prehistoric France in 15,000 B.C., a Rembrandt oil portrait made in Holland in 1655, and a poem published in Japan in 1689 speak to us today of things we feel are deeply significant and true? Yet they do.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self Portrait, 1655

When you look with a sensitive eye at Rembrandt’s 1685 self-portrait (above), you see a man deeply thoughtful, intelligent, far-seeing and sad. The way the figure’s face emerges from the nebulous masses of darkness makes him seem small and vulnerable. Rembrandt piles on and scratches into the paint, deliberately leaving the surface rough, as if corroded yet chiseled and hacked into existence despite all odds.

The marks he makes, and how he makes them, express essence: his features are intense and above all telling of age; the lined brow is knotted with worry, the cheeks and temples blue-veined and sunken; one side of the mouth contracts, as if pinched into a pout, the eyelids are heavy and sag, and the eyes – the eyes! They’re like marbles made of volcanic glass; or rather pools of dark water. They look lustrous too, opening on infinite depths – a quality that used to be called “limpid.”

Why’s it great? Because it’s so much more than a likeness; the light, color, texture, and emphasis on particular features and not others work together – to do what? They combine to honestly express a non-idealized psychological depth of experience, knowledge, and feeling for life’s intangible truths that we recognize as the human condition. Not without reason is Rembrandt considered one of the greatest artists who ever lived.

Closeup of Rembrandt’s 1655 self-portrait above

And technique? It simply came down to how best to get paint to express his intuition about his subjects. In other words, the formal aspects of his paintings all express his own “latent conviction,” what he felt to be his truest and most personal visions of life.

It just so happened that Rembrandt was also as insightful and sensitive as Shakespeare to the breadth and depth of human experience – “the human face, daily altered by experience, and the heart’s journey through love, grief, despair and every imaginable emotion,” as art historian Laura Cummings puts it.

Van Gogh, who once wrote that he would give a decade of his life to sit for two weeks in front of Rembrandt’s painting, The Jewish Bride, with nothing but crusts of bread and water, spoke for all humanity when he said: “Rembrandt says things for which there are no words in any language.”

Now to Japan and an even more compressed and enigmatic meditation on the poignance of aging. The following poem was written into a travel journal that the poet Basho kept during what would be his longest and final journey traveling from temple to temple across the Japanese countryside as an old and dying man:

Sickened to the bone

If I should fall, I will lie

In fields of clover.

You have to read it a couple times before it sinks in. Go ahead, read it again, carefully. I’ll wait.

And there it is: end-of-life reality tied up with the beauty of young, sweet life still springing beneath your heels. Sidestepping any common, sentimental lament, this timeless work of art gifts us with a soft, sad irony.

Consider that even in our own time and place, the old (1700s) expression “in clover” means prosperous, living well, having it made. Does the prospect of lying in fragrant clover on a beautiful spring day mean the old man welcomes death? That’s one reading, but the poem never says so.

Basho’s poem only places the two things side by side – life and death, youth and age, a moment, perhaps, of longing for the end of pain and ill health, and fear of what it would mean to give in to that tempting desire – none of it’s stated but all of it’s there.

We know more than what the poem literally says, and we know more than Rembrandt’s painting says about “how he looked.” Art brings us to the universal foundations of human experience. If just for one incredibly brief moment, we can feel life’s timeless truths “to the bone.”

And yet, you DO have to learn technique. Contemporary artist Eric Johnson gives expert instruction on the Old Master approach in the video Rembrandt Secrets Revealed, summing up hundreds of years of attention given to just how the Master made the rough magic that he did.