Vermeer’s painting, Lady at the Virginal with a Gentleman – The Music Lesson, (variously known as The Music Lesson, Woman Seated at a Virginal or A Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman) is as much a study in subtlety and suggestion as in rigorous, strictly accurate scientific perspective.

Nothing here is not measured, intricately thought-out, manipulated, calculated and controlled, aesthetically, mathematically, and symbolically. In Dutch genre painting, for one thing, music was often a symbol of love. Thus, in Lady at the Virginal, Vermeer alludes metaphorically to the harmony of two souls in love.

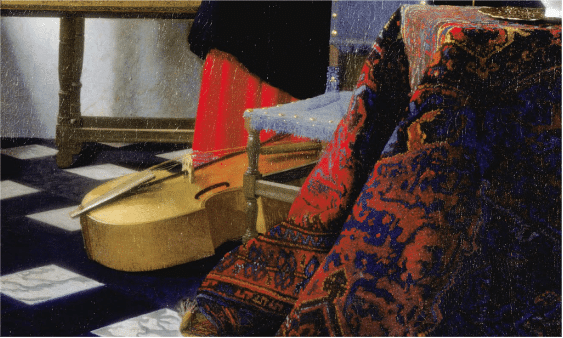

Reading symbolically, as we know the Dutch artists and their viewers were used to doing, we see the musical keyboard the woman plays (the “virginal” of the title) and an unattended cello-like instrument half-hidden on the floor (called the “viol de gamba”) together implying a visual connection between student and teacher.

Perhaps, too, there is something in the vivid color of the lady’s half-covered dress – a glowing red, the exotic color of love and passion enflamed.

As these symbols traditionally alluded to “harmony,” Vermeer achieves the suggestion of a veiled amorous relationship between the demur young virginal player and the gentleman beside her.

The subtle clues to meaning come forward the closer and deeper you look. For example, although the music student faces the virginal directly, the image in the mirror has her head turned, facing and inclining toward the man (Vermeer changed the woman’s posture but left her reflection to tease this shade of meaning).

Vermeer knew exactly what he was doing, and this subtle change embeds the question of a secret attraction, possibly a clandestine affair, some sort of a relationship between these two people that remains hidden under the surface appearance of things.

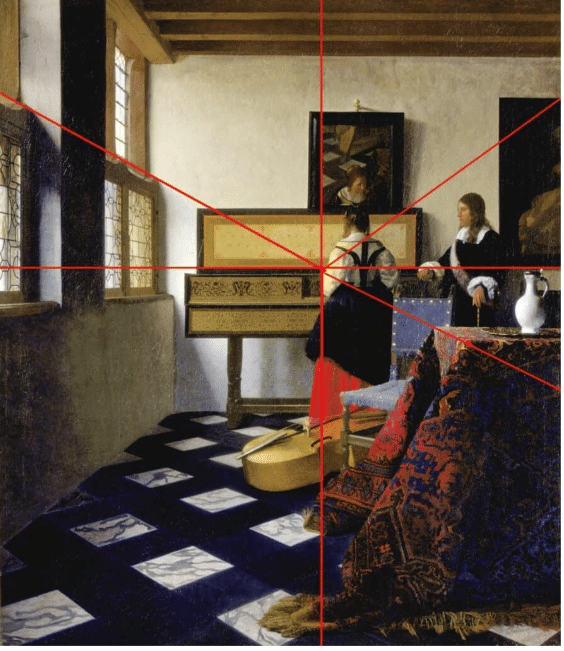

Other commentators see in the composition itself the key to the painting. “Its significance is in its design,” says one. “Of particular interest is the perspective. The Vanishing Point is just at the point of the woman’s sleeve, you can take a ruler and see that all lines lead into that and the composition has been planned with incredible mathematical accuracy.”

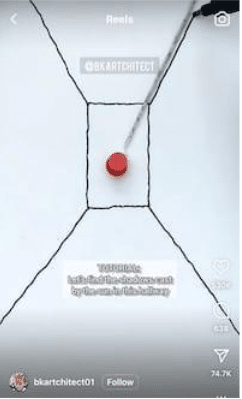

As illustrated in the Instagram screen-snap above, you can attach a piece of string to a thumbtack and any lines you draw from any point on the periphery (as you swing the string around in a circle) will create totally accurate one-point perspective. This is what Vermeer did for most of the architecture, with the important exception of the tiles on the floor.

Floored!

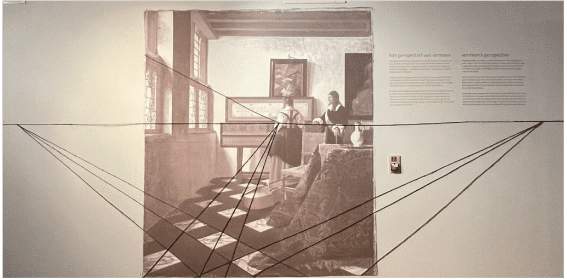

If you visit this painting in person, you’ll see a wall plaque with the following information about the perspective:

“Vermeer makes much use of the ‘angular’ perspective: with two vanishing points instead of just one. In this way he produces his well-known tile floors, which create an additional three-dimensional effect. If you trace lines outward from the joins between the tiles, you arrive at two points far outside the painting.

“In Vermeer’s time, perspective was also known as ‘see-through skill’: you had to be able to see through walls and the frame of the painting to be able to use it!

“Vermeer and his contemporaries used lengths of string and chalk as tools to allow them to ‘see through’. In some of Vermeer’s paintings, there are still minuscule holes left by the pins where the string had been attached.” (see screenshot above)

Photo: Elaine Miller

So we find in this Vermeer, as in his other paintings, an unparalleled marriage of rigorous draftsmanship and a sense of the half-discovered poetry beneath the surface of everyday life. And that is the perspective of a true artist.

To learn how to apply these and more of Vermeer’s methods, check out the video Traditional Oil Painting: The Principles of Visual Reality,

in which Virgil Eliot brings his very popular book of the same title in which he shares his understanding of the techniques of Johannes Vermeer.

Ranked a Living Master by the Art Renewal Center, Virgil has earned his stripes in the art world many times over.

That’s why he’s been on the ASTM International Subcommittee on Artists’ Paints and Materials since 1996. And he has spent decades understanding the techniques of Johannes Vermeer, the great Dutch artist. The book and video are also available as a specially priced set.