This ought to be taped above my easel, my computer, the door to my life.

But it isn’t, because it wouldn’t do any good. I can tell myself this a thousand times, I can tell you this, I can tattoo it all over my arm like a hipster “sleeve,” but guess what? I’m doing it again. Right now. Even worse, now I’m thinking about overthinking.

Maybe I stand a better chance of getting out of my own way by thinking about what’s really going on here? Maybe I need to step back from what I’m thinking and think about what I’ve been thinking.

So what is happening in my head here?

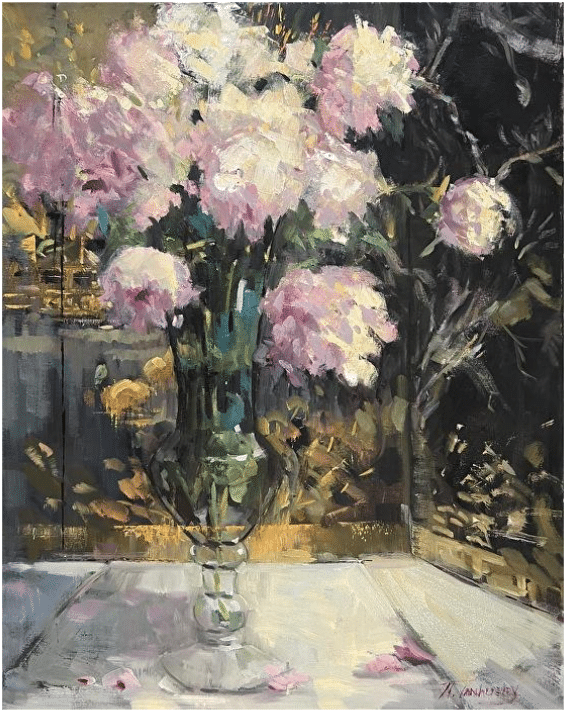

Kyle Ma, Still Life with White Roses, oil on panel, 12 x12 in.

Painting Paralysis

Overthinking a painting you’re working on happens when you start mentally asking too many questions about what you’re supposed to be doing, that is, what the painting is supposed to look like. It’s not wrong to try to see your painting from the perspective of an imaginary viewer. I think almost all artists have to do some version of that if they ever want to show their work. It’s a tricky tightrope walk though.

The problem comes in when you aren’t clear about that imaginary viewer and their imaginary expectations. It’s hard to please an imaginary person if you don’t know enough about their imaginary tastes in art and aren’t sure what they’d be looking for or expecting to see in your finished work anyway.

The solution for this problem is to get to know your imaginary viewer a little bit better. Since they’re just a construction of your own mind, the more YOU learn about art – what’s good, what’s bad, what YOU like and what you don’t – the less you’re going to find yourself spinning trying to second guess a ghost.

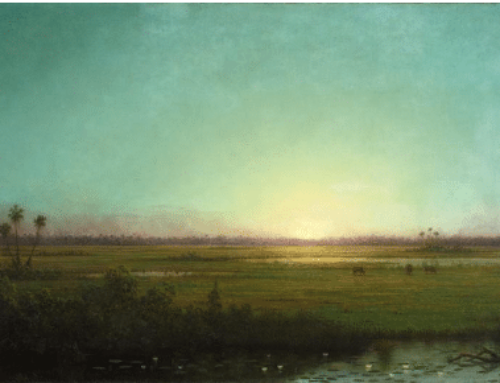

John Michael Carter, Carnations, oil on linen, 30 x 40 in.

In other words, you have to do the hard work of looking at a lot of art and learning about it – first figure out what you find important or valuable about a work you know is “good.” Then dive into the many choices that artist made in getting that work to completion. Learn enough about art to decide for yourself what a work of art that you admire is doing and how it’s doing it.

Creative Paralysis

Once you’ve got a pretty good idea of “what’s good” and how to do it, most of the overthinking happens not during paintings but between them. The root cause is the same though – it’s fruitlessly comparing yourself to others, trying to assess your work in terms of what other people are doing or saying (and that without really knowing enough about what that is or why).

For that matter, if you’re putting yourself into your work at all, it gets almost impossible to assess it with anything resembling objectivity. How can you begin to guess how your work compares, when you don’t even know enough about how people see your work now? That’s the value of critiques, however painful – they let you practice dividing your work from yourself. Your work is not you.

Pat Fiorello, Wall of Flowers, oil, 9×12 in.

Part of it is very much you, or should be, but a lot of it’s “everything else” – technique, theory, blah blah blah hundreds of years of art history (!). Suffering a critique, even an unjust or ill-informed one, helps create some distance between you and what’s on the canvas. One trick here is to seek out worthy mentors and bother them for their opinions. (Only problem is they’re often in short supply.)

Bottom Line: Keep Going

Maybe the true antidote for all of this is to Keep Going. Just work. Put your head down and make your work. Lost in a painting? Put it aside for now and start a new one. Stuck on a foreground? Work on the clouds a while and come back to it later. Not sure if the most recent painting is pointing the way forward to your next new body of work? Make another one and you’ll find out soon enough. Doubting whether your work is going to do x, y, or z out in the world (e.g. get you into a gallery, win acceptance to group show X)? Forget it. None of that’s in your control.

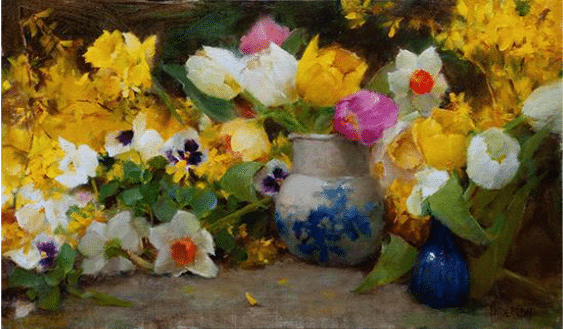

Nancy Tankersley, Floral Still Life

Speculating about your work is like running an imaginary race without realizing you’re on a treadmill. The best thing to do when grappling with ideas and doubts is to 1. learn more and 2. work out the questions in lots of small paintings – NOT in your head.

If you’re an artist or want to be one, one way or another you’ll keep moving forward.

Interested in painting flowers? The artists in this issue have the know-how and the ability to teach it. Everything you need is available in a multi-video download right now – check out Streamline’s FLORAL IN OIL BUNDLE.