Cityscape paintings can range from decorative to abstract, and from visceral to hyperrealistic. This is part two of a two-part timeline survey of the genre.

Japanese Woodblock Prints

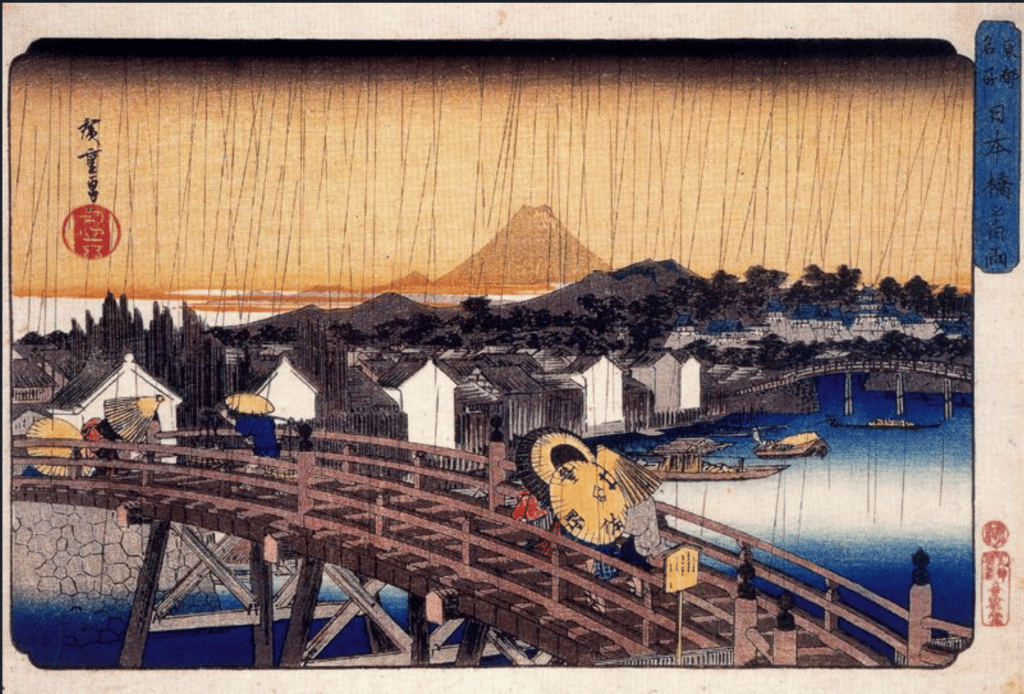

Utagawa Hiroshige (Ando) (Japanese, 1797-1858). Shower on Nihonbashi Bridge, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital, ca. 1832.

Japanese color woodblock prints are among the most beautiful as well as influential landscapes ever made. Traditional Japanese printmakers adored scenes from everyday life of all kinds, crowded fishing ports, busy villages and bustling cityscapes included. The impact on Western art is hard to overestimate; the proto-Modernism of artists like Gaugin, Whistler, and Matisse would be unthinkable without the the prints and reproductions of Japanese art that began proliferating in France in the late 1800s. European artists were wowed by the refreshing formal characteristics – wonderfully simplified details, deep colors, brilliant design and compositions with strong diagonals, asymmetrical arrangements, dramatically foreshortened perspective, and an emphasis on flat, linear design.

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) was one of the best known of all Japanese woodblock print designers. He is particularly renowned for his landscape prints, which are among the most frequently reproduced of all Japanese works of art. Hiroshige’s landscape prints were hugely successful both in Japan and in the West.

Modernist Abstraction

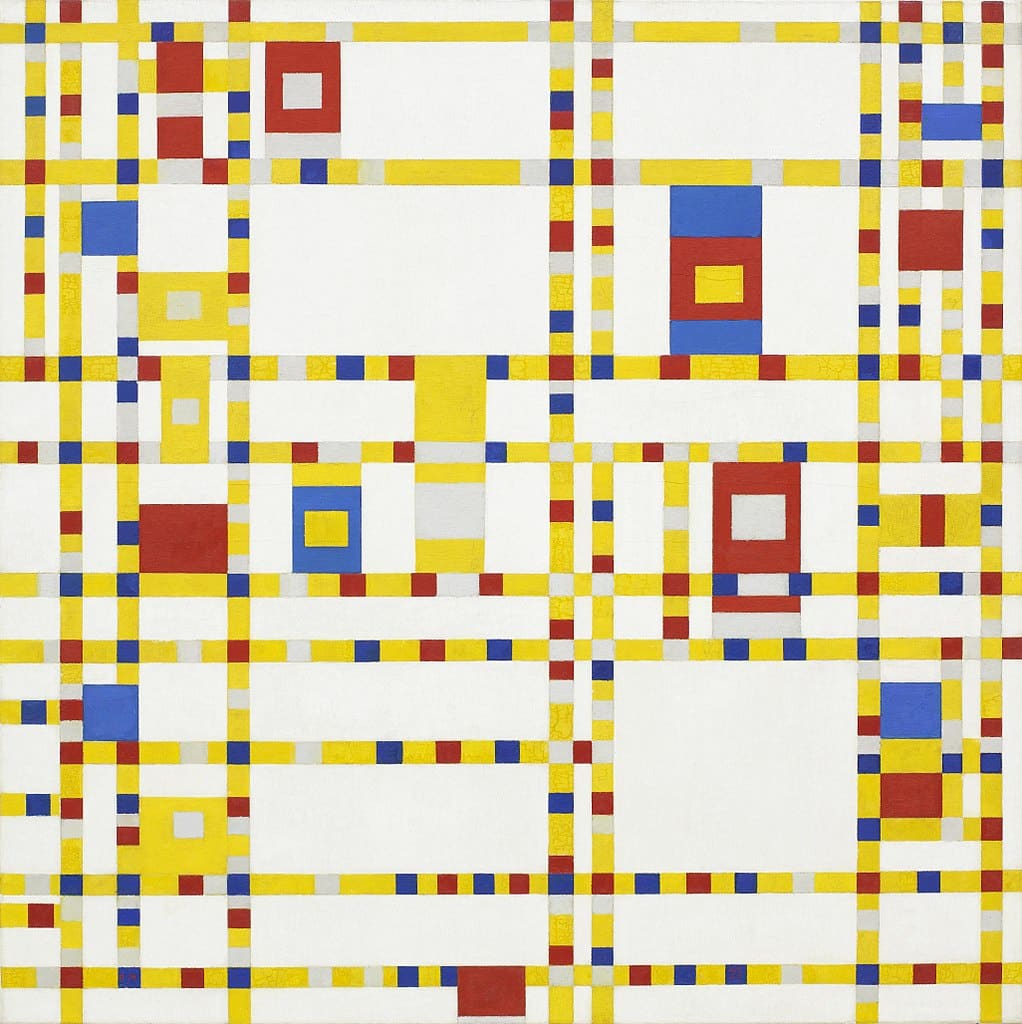

Piet Mondrian, 1942 – Broadway Boogie Woogie 50 x 50 in

Fast forward to the era of Modernism, and we find something close to the opposite of observational painting in Mondrian’s iconic Broadway Boogie Boogie of 1942. Here the city appears as a kind of shorthand notation instead of even a quasi-realistic representation.

Mondrian sweeps the rules of perspective and observational painting off the table to reimagine blocks of buildings, streets, and traffic as a map-like grid consisting of visual art’s bare-bones essentials: a radically different kind of beauty consisting solely of geometric form and primary colors. It’s almost like a Platonic Ideal, the archetypal blueprint of all cities.

Like saxophone notes in a jazz composition (to which the title alludes), Mondrian’s blocks and spots of color seem to blink on and off in syncopated motion. The painting as a purely intellectual experiment conveys the idea of the constant neon, traffic lights and jostling thoroughfares of the modern city – even as it exists quietly in its own world as a beautiful, non-representational abstraction, pleasing to eye and spirit on a whole other level than that of the senses alone.

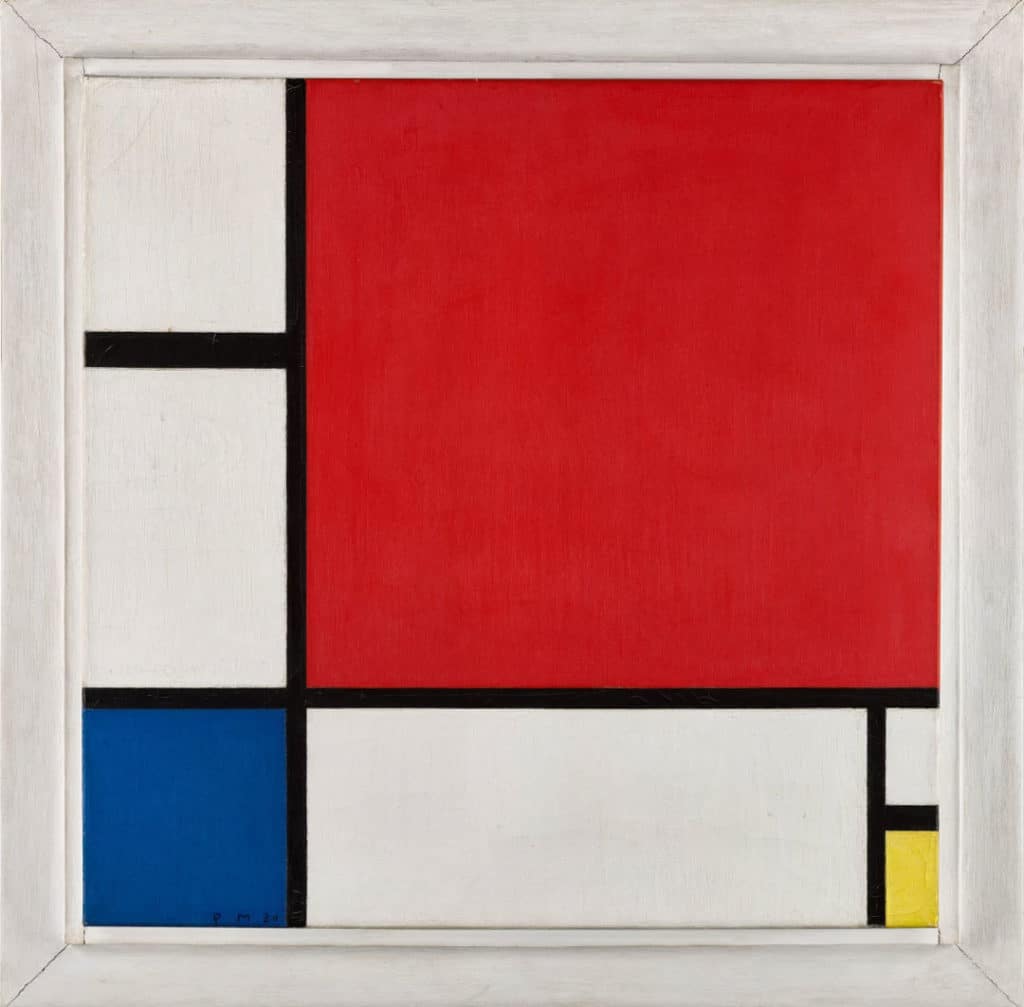

Mondrian, Composition III, 1930

By the way, Composition III (above), one of Mondrian’s “city” (i.e. “Parisian”) paintings will be offered at auction next month, with an estimated price tag of $50 million.

Abstract Expressionism

City Landscape, oil on linen, 203.2 × 203.2 cm (Art Institute of Chicago 1958.193, ©The Estate of Joan Mitchell)

Putting bodily sensation and the visceral feeling of the city back into the picture (despite her protestations to the contrary), New York School abstract expressionist Joan Mitchell’s City Landscape of 1955 blares with the fierce and loud frenetic pace of urban life. She insisted her paintings were “about landscape, not about me,” according to the Art Institute of Chicago that owns it. Nonetheless, her “large, light-filled canvases animated by loosely applied skeins of bright color” are nonetheless full of personality and “infused with the energy of a large metropolis” as filtered through the artist’s sensibility (rather than her eyes). At about six feet square, the painting above is as confrontational and overwhelming as the American city itself.

How and why one would want to do paint a cityscape the feels like a city without looking like one is the subject of a wonderful conversation between Sarah Alvarez, Director of School Programs, Art Institute of Chicago and art history profs Beth Harris,and Steven Zucker, watchable at the link below.

Return to Realism

Antonio López Garcia: La Gran Vía, Madrid, 1974-81, about 4 ft. long

At nearly 90 years old, Spanish painter and sculptor Antonio Lopez Garcia has pursued his signature brand of realism for some 50 years. Future art historians will probably cite his work as a major force in the contemporary resurgence of interest in realistic painting. Antonio Lopez Garcia has drawn criticism by some major modern artists for what they consider his neo-academism, and he has received praise from some prominent art critics, such as Robert Hughes, who in 1986 called him “the greatest realist artist alive.”

His large cityscapes of his native Madrid are notable not only for their gorgeous palettes and incredible detail, but for their special distinctive atmosphere, a signature characteristic that identifies the work as no one’s but Lopez Garcia’s own. Despite their size, he paints them outdoors, setting up in the same place sometimes for days at at a time.

Antonio Lopez Garcia painting on site in Madrid

Contemporary Plein Air

Scott Tallman Powers, Urban Reflections, 16″ x 20,” oil on canvas

Landscape painter Scott Tallman Powers has a video on how to capture an outdoor Chicago scene on a rainy day that breaks down the process in fine detail. His running commentary explains exactly how, why, and what to do and not to do – from the underpainting to the final brushstroke. It’s another one of many instructional videos on painting the contemporary cityscape.

7 Tips for Painting the City

In case you missed it, here’s a down and dirty set of tips to keep in mind the next time you plant your easel in a doorway on a crowded city street.