Behind the floodlights of abstraction, traditional landscape painting carried quietly on through the 20th century in all of its previous forms. Today, artists freely avail themselves of the whole gamut of historical styles. Abstraction seems to be gently infusing traditional landscape painting with various types of wildness on a regular basis.

This is mainstream art catching up with the avant-garde. As early as the latter half of the 20th century, abstract expressionism and landscape painting collided in the work of numerous artists, such as Anselm Keifer, Helen Frankenthahler (see second story, below), and Richard Deibenkorn.

Richard Diebenkorn, Seawall, 1957

Diebenkorn (1922-1993) is considered a primary painter of the Bay Area Figurative Movement, a subset of the “second generation” of mid-century abstract expressionism. In paintings like Seawall (1957), Diebenkorn abstracted the California landscape into the flattened geometric shapes and color-fields we associate with modernism (particularly Matisse) rendered with the “gestural” paint-handling of the abstract expressionists.

Gerhard Richter, Venice, 1986

Today, German artist Gerhard Richter consistently tops critics’ lists of the world’s greatest living painters. For his landscapes, which he started making early in his career during the 1960s, Richter drew inspiration from amateur photography and from historical Romanticism; he is particularly fond of German painter Caspar David Friedrich, the 19th century Romantic artist we looked at in the previous post in this series.

In Richter’s painting above, titled “Venice,” nothing is as it first appears. At first glance all appears to be some sort of messy chaos. Look longer and you see the painting is neatly divided into a symmetrical 2 x 3 grid. Then, what at first glance seemed a photo underneath expressionist brushstrokes turns out to be, like most of Richter’s landscapes, painted photo-realistically but from several photographs collaged together into one single image that could never exist in the world. Richter has painted this land mass using three distinct spatial scales and three different styles of painting employing varying degrees of realism and abstraction. Each of the three segments of the landmass leaves its own distinct and unrealistic reflection while the whole thing masquerades as a blurred photograph of a deliberately uninteresting bank of trees.

The whole painting, then, is a postmodern meditation on what the art world expects landscape painting to be. It ‘s made to question of the art of painting and image-making itself. By the way, Richter popularized the now commonplace use of squeegees in landscape and abstract painting – another attack on the conventional expectations of what a painting is, should, or can be.

This gorgeousness is the sort of thing Richter is known to make using giant 7-foot squeegees.

Virtuosity and innovation are what make Richter, as The New York Times once put it, an “artist beyond isms.”

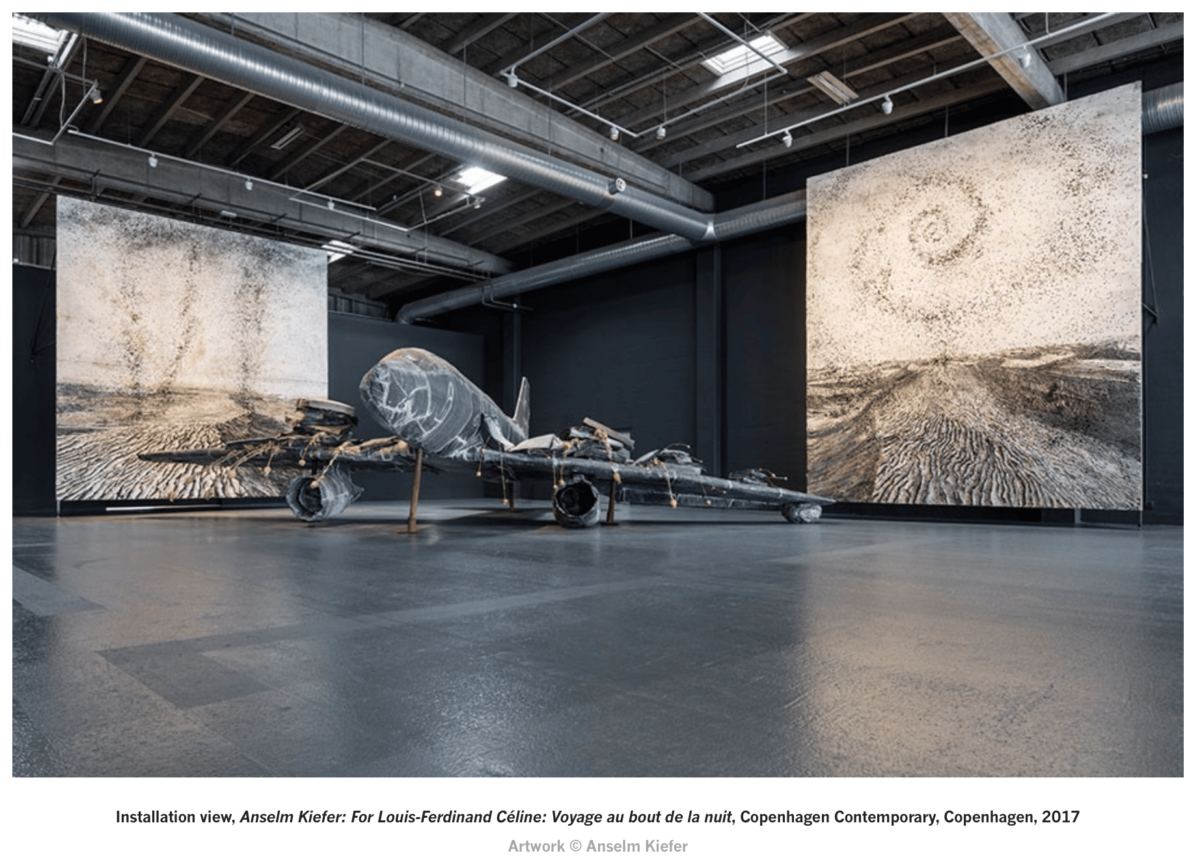

Our final landscape (there have been more than six but who’s counting?) is by Anselm Keifer, also a contemporary German artist of Richter’s generation. Keifer is represented by Gagosian, perhaps the leading “blue chip” gallery in New York City. Richter’s gallery recently exhibited four new monumental paintings by Keifer under the evocative title “Field of the Gold Cloth,” including the following:

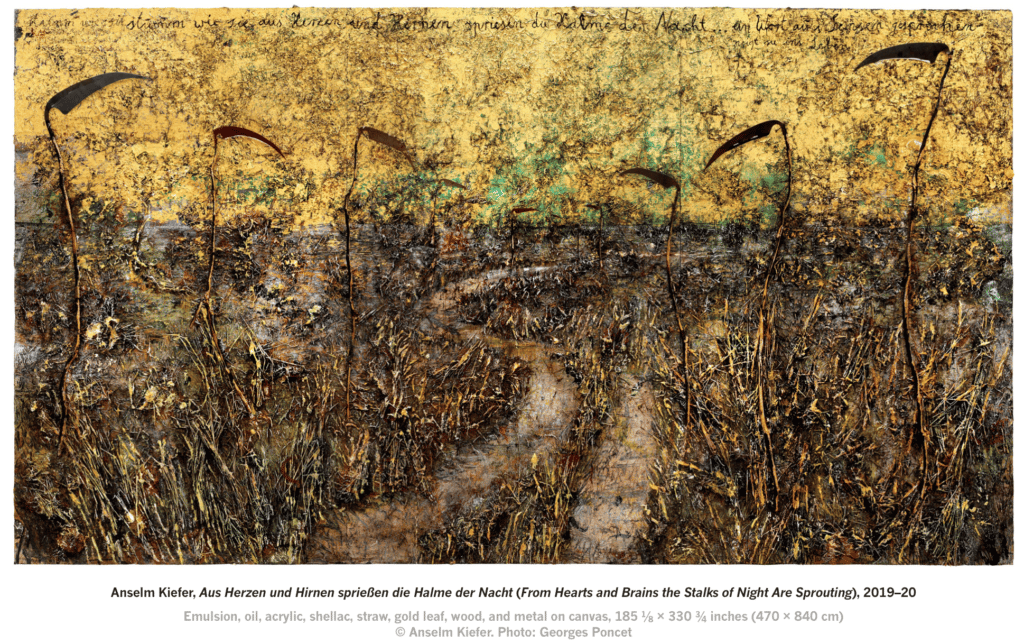

In this at once beautiful and haunting (haunted?) landscape, titled From Hearts and Brains the Stalks of Night are Sprouting, Keifer gives us long-stemmed black scythes growing (?) from a muddy, bedraggled roadside of decaying crops beneath a cosmos glowing with the gold of the celestial Heavens, splashed with a translucent green evocative of new growth. Keifer is known for exploring the brokenness of modern spirituality by confronting his native Germany’s guilt and trauma inherited from the horrors leading up to WWII.

“The tension between beauty and terror, alongside the inextricable relationship between history and place, has animated Kiefer’s work since the 1970s,” says Gagosian. “He infuses the medium of paint with startling and unconventional gestures and objects, juxtaposing it with organic and abject materials such as straw, sand, charcoal, ash, and mud… His paintings undergo various processes—such as being cut, burned, buried, exposed to natural elements, splashed with acid, or poured over with lead—so as to be made anew. These strategies, along with the use of materials such as lead, concrete, glass, fabric, tree roots, or burned books, create a symbolic resonance, making palpable both the movement and destruction of human life and the persistence of the lyrical and the divine.”

And that about says it, folks. Massive, visceral, and riveting in person, Keifer’s landscapes must arguably be counted among the greatest works of any living artist.

Full-On Abstraction with a Side of Landscape

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011). Stella Polaris, 1990. Acrylic on canvas, 96 x 108 in. Collection of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York. © 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Naples, Florida, home of The Baker Museum and the Naples Philharmonic, is currently exhibiting “Helen Frankenthaler: Late Works, 1990-2003,” a “landmark” presentation of the artist’s work. Frankenthaler’s work is primarily abstract, though elements of her experience of landscape, particularly the colors and shapes of a given place, at times play an important role in her work.

In the paint,

Chris