This is a black and white painting by one of the artists of the famed Lyme art colony in Connecticut. It’s a virtual blueprint of landscape technique – the absence of color lets us study the values – the crucial distribution of varied lights and darks that define volumes and forms.

Speaking of lights and darks, check out this neat old trick: One of the areas of perhaps the greatest contrast between light and dark in this can be found in the stand of trees on the left side – where the tallest tree’s trunk, catching the light, shows up against the darker shadows behind it. It’s a tiny but significant detail, and it’s counterintuitive, because it isn’t about the color or the value of the tree trunk on its own – it’s all about the contrast: note how the same tree’s trunk is dark, not light, after it clears the tops of the darker trees and is backgrounded only by sky. It’s painted light against dark but dark against light.

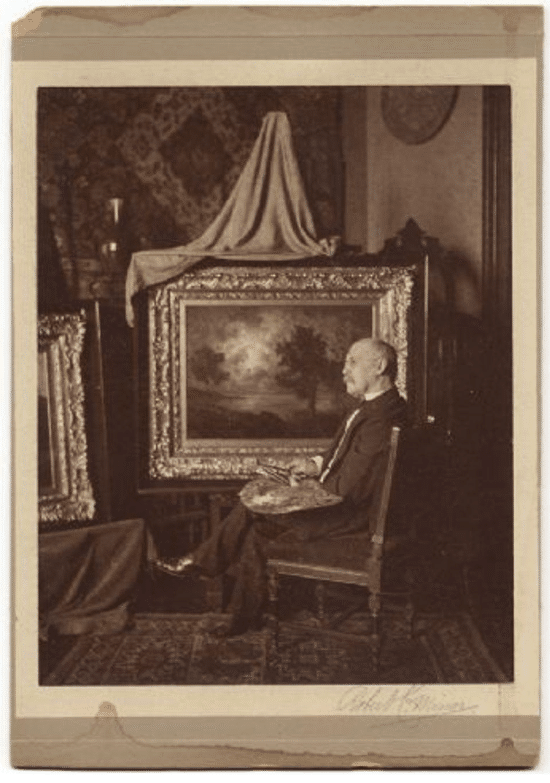

The painting, titled Landscape with Pool is by one Robert Cranell Minor, now largely forgotten but once called “the dean of the Lyme colony of artists.” Here he is:

The Lyme colony started somewhat by chance in 1899. That year, Florence Griswold, as aspiring painter and matron of a once wealthy family, decided to take in boarders to offset the expense of keeping up her family’s estate. The prominent landscape painter Henry Ward Ranger, having recently returned from study in Europe, was eager to start a colony modeled on the French Barbizon.

Ranger saw in Old Lyme the ideal setting for establishing a new American “tonal” school of landscape painting. He found “Miss Florence’s” home the perfect place to settle. The Griswold House offered a stimulating environment, artistic camaraderie, inexpensive lodging, and picturesque scenery. Conveniently located between the cultural hubs of Boston and New York in the lush countryside of Connecticut, Lyme soon attracted a flourishing colony of artists, and Minor was a major player.

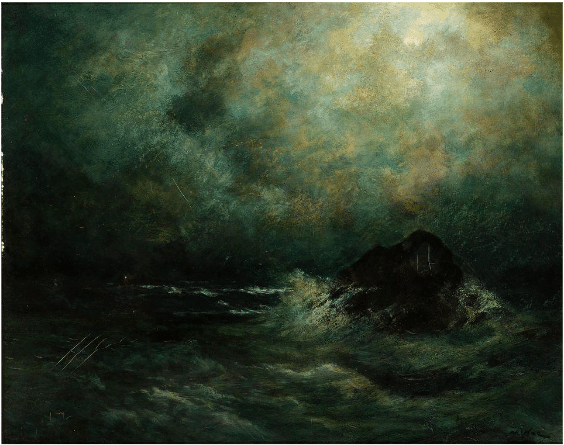

The most remarkable of Minor’s paintings known today is probably Great Silas at Night, 1890, a small (16×20 inches) but powerful tonalist meditation on the sea at night. I can’t find any information on the title, but I assume it refers to the large rock looming in the foreground. It’s thought that the painting may be a view of the Connecticut coastline – if so, it would be nearly a line of sight from Greenwich Village, where Minor was living and painting at the time, to the future site of the Lyme colony. A pinpoint of light from a lighthouse is just visible in the distance, emphasizing the scale of the waves and the potential danger that faced ships sailing off the coast. The painting is owned by the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.

Robert C. Minor, Great Silas at Night, 1890, oil on paperboard, 16 x 20 in. (40.7 x 50.7 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of William T. Evans, 1909.7.48

But let’s return to Minor’s Landscape with Pool painting of 1903. Minor painted this in black and white probably because it was intended to be reproduced in print. As such, the painting all the more vividly conveys the Tonalist sensibility and strong contrasts that characterize many of the Lyme colony paintings.

Minor probably never saw this scene; he spent the last decade of his life housebound in the nearby town of Waterford, disabled by an illness that made it hard for him to paint, much less travel. This work is probably a poetic composite of memories and motifs common to turn of the century Tonalism and “American Barbizon” painting.

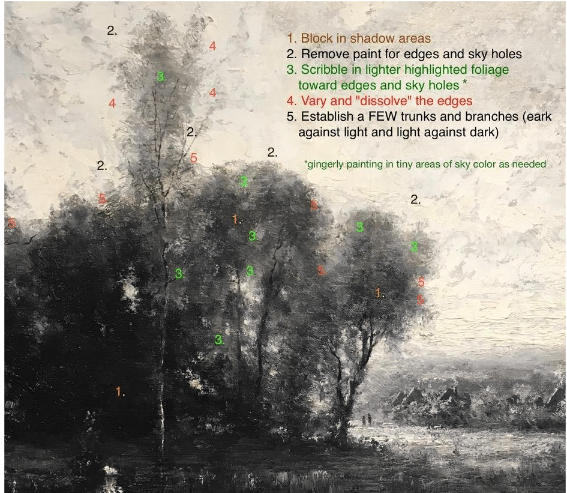

Here’s my best analysis of the technique Minor and others used to create believable and evocative banks of trees and foliage (without fussing over too many individual branches or leaves).

It looks to me like the shadows were laid down first, then the mid-tones, the sky hole, then the (minimal) trunks and branches, then a scrim of scribbled lighter-valued highlights over top, some adjustments of the edges, and finally maybe another branch here and there.

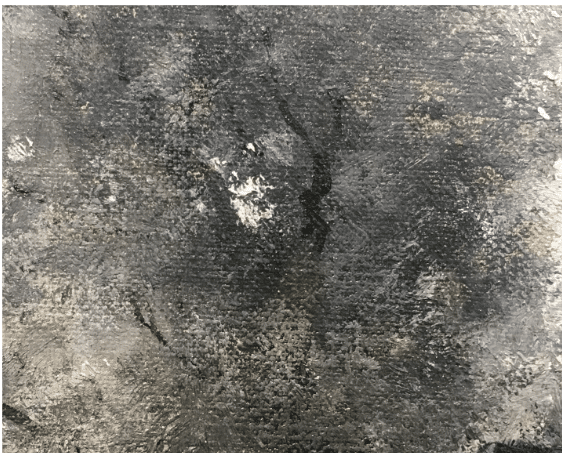

In the next detail of another portion of the painting you can get a closer look at what’s going on technique-wise.

As you can see, neither the underlying shadows (added first), the mid-tone foliage masses or the highlights are meticulous – it was all roughed in quickly, by dragging or (softly) grinding a sparsely-loaded medium-to-large brush across the surface, twisting and turning the brush in a fluid motion. Only the sky hole and the scant bits of branches and trunk (added toward the end of the work) took careful linear draftsmanship.

There’s a closeup of the sky hole below (note that it’s the only one that’s fully developed in the whole tree. With sky holes, less is more.). A good way to keep sky holes believable is by

- limiting their number,

- significantly varying their size and shape (make sure no two are alike!)

- gingerly “stabbing” them into place with a series of small, irregularly varied dabs with the tip of a (round) brush.

A lot of this has to do with the quantity of paint on the brush (not too much), how you “scrub” it on, and the amount of pressure you do it with.

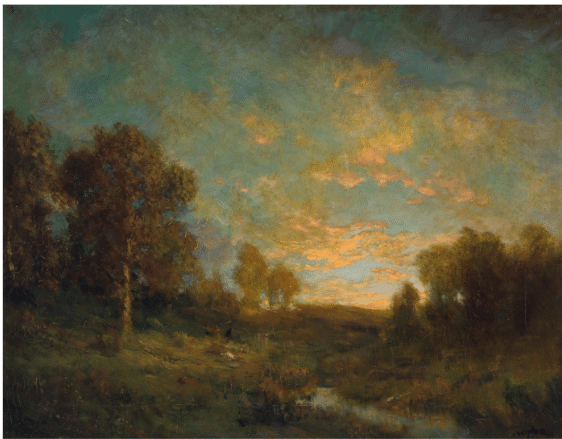

Finally, to relieve the black and white gloom, here’s a particularly pretty Minor, showing the results of the same techniques with the addition of color.

Robert C. Minor, Twilight Landscape, c. 1900

Robert Burridge shows the way to a contemporary approach to trees that’s fun and not fussy. His video Painting Abstract Landscapes takes from start to finish the “abstract” landscape inherited from Barbizon and tonalism by way of abstract expressionism.

Inspired by the Sea

By Kelly Kane

While the term seascape first gained popularity around the turn of the 18th century, the practice of depicting oceans, ships, beaches, and coastlines stretches back to antiquity. Portrayed on everything from rock walls, etchings, paintings, pottery, and tapestries, views at sea or from the shore have long fascinated humanity. Here, three contemporary artists put their unique spins on this timeless subject.

Watercolor Paintings of the Sea

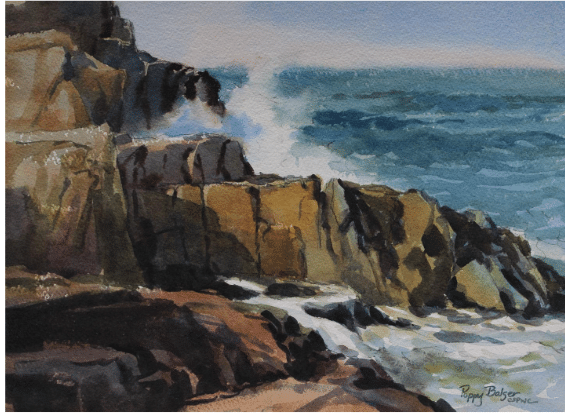

“November Seascape” (watercolor, 11 x 15 in.) by Poppy Balser

“I painted this piece on the shores of the Bay of Fundy, the day after a November gale,” says Balser.

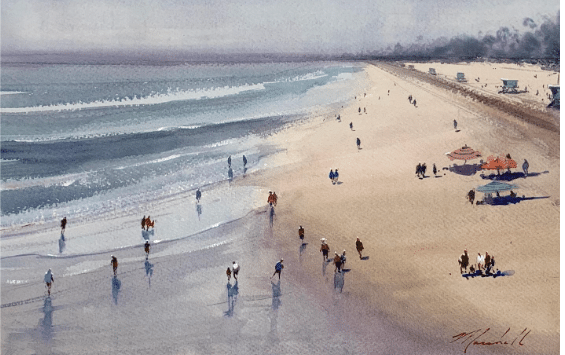

Winter Beach” (watercolor, 14 x 21 in.) by Dan Marshall

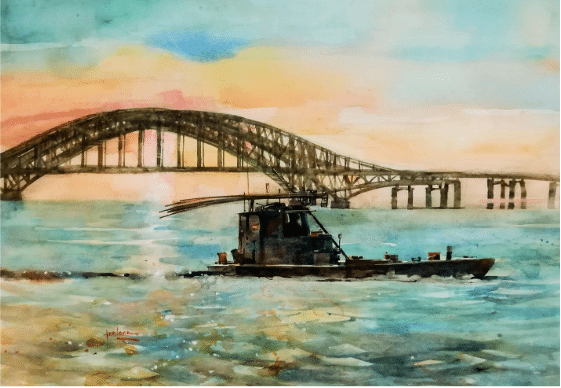

“The Clamming Boat” (watercolor, 15 x 22 in.) by Francesco Fontana

Let Shuang Li open your eyes to a different way of looking at water. In Fearless Waterscapes, you’ll discover that unlike other subjects, water can’t be directly translated from a photo to a painting; you have to first learn the language.