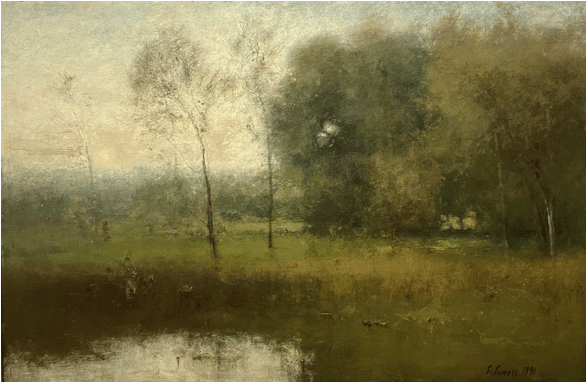

I used to think this painting was titled “Summer,” I guess because it seemed, in my memory of it, to convey the end of a hot, hazy day among tall grass, ponds, and woods, all of which must correspond to some now buried memories from my youth. Or perhaps it is an image from the youth of the world? Either way, there is, most deliberately, something universal, and in Inness’s eyes, spiritual contained within it.

George Inness was the most revered American landscape painter of the late nineteenth century. By the 1880s, the Hudson River School had run its course, and Inness’s painting began to show the influence of French Barbizon painting (but not Impressionism – Inness hated Impressionism for what he saw as its lack of substance). Inness took from Barbizon painters such as Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot the poetic diffusion of form through judicious blending and glazing (applying semi-opaque layers of paint on top of one another). For him though, the technique suggested the permeability of the material world and its inter-penetration by the spiritual realm.

The fact that this painting is titled New Jersey Landscape seems the art historical understatement of the century. Who cares where it is? The location is not the point of the painting. On the contrary, what makes it so great is precisely that it is everywhere and nowhere (in North America, that is). In other words, Inness’s approach to painting was to use the physical, material world to image forth the spiritual, immaterial realm. As is obvious from these later paintings, what he really cared about was a higher reality and how art and vision could combine to access and hold it here on earth. Inness’s imitators would go on to found a style now called the Tonalist movement, but the original impulse was poetic and spiritual in nature.

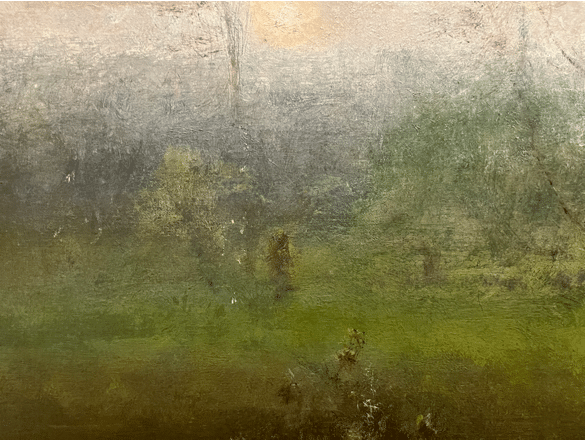

Detail, George Inness, New Jersey Landscape, oil on canvas, 1891. Clark Museum.

The edges and the borders between things in Inness’s late landscapes often fragment, waver, and dissolve. As one thing merges into another, we’re not always sure what we’re looking at or where one thing ends and another begins. It would seem this was Inness’s way of saying everything is connected yet ultimately an illusion (in the same sense that Plato and many world religions say the physical world is merely a provisional image of eternal spiritual realities).

Spirit-Trees: detail, George Inness, New Jersey Landscape, oil on canvas, 1891.

Look how Inness’s trees manifest from clouds and mists of paint. Nowhere can you point to a single leaf (so NOT the case in the Hudson River School painters, such as Cole, Cropsey or Durand). It might look easy, but consider how Inness had to unite such subtle and not so subtle variations of tone among the dark and light and warm and cool greens in this segment. (Hence “tonalism.”)

Detail, George Inness, New Jersey Landscape, oil on canvas, 1891. Clark Museum.

But Inness’s spiritual approach went beyond the dissolution of physical form. The spirituality was embedded in the composition itself. That is to say, the artist worked out a personal mathematical underpinning for his landscapes that for him corresponded to ideal “sacred geometries” within nature. Unfortunately, the notebooks containing the elaborate system that Inness is presumed to have worked out have been lost.

An attempt to diagram the painting in search of a hidden armature yields only an uninformative series of lines with enigmatic divisions. Nothing is revealed except that the symmetries don’t correspond to standard compositional strategies.

A diagram of New Jersey Landscape tells us virtually nothing about how or why Inness composed the painting as he did.

The Clark has this to add: A follower of the Swedish mystic-philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg, Inness believed that the spirit of God was present throughout the natural world. Although this painting may represent a specific place, the artist was less interested in defining recognizable details than in conveying nature’s immaterial essence, here expressed in finely modulated colors that have been painted with a brush and then wiped with a cloth, so they blend together without contours.

On the technique side, it’s instructive to look at how Inness rendered standalone trees and branches.

Detail, George Inness, New Jersey Landscape, oil on canvas, 1891. Clark Museum.

To make these trees, he hastily indicated the trunk and perhaps a main branch or two and just daubed the “foliage” into place with a few light taps or drags of a gnarled old brush. He then mostly scratched in the smaller branches with the handle-end of the brush.

Detail, George Inness, New Jersey Landscape, oil on canvas, 1891. Clark Museum.

Detail, George Inness, New Jersey Landscape, oil on canvas, 1891. Clark Museum.

Inness’s desire to represent the spiritual embodied by, or seen through, the physical recalls a basic aspect of the “perennial philosophy”: the aim of spiritual vision, summed up in these lines from artist and poet William Blake:

To see the World in a Grain of Sand

And Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

If you’d like to pursue tonalism as a technique in your own work, you might want to consider the teaching video Tonalism with Mary Garrish.

How Plein Air Artists Honor the Fourth of July

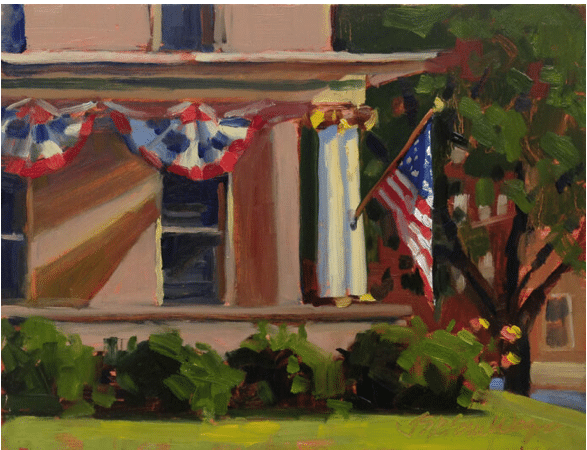

Jill Wagner, “Flying the Flag, Too”

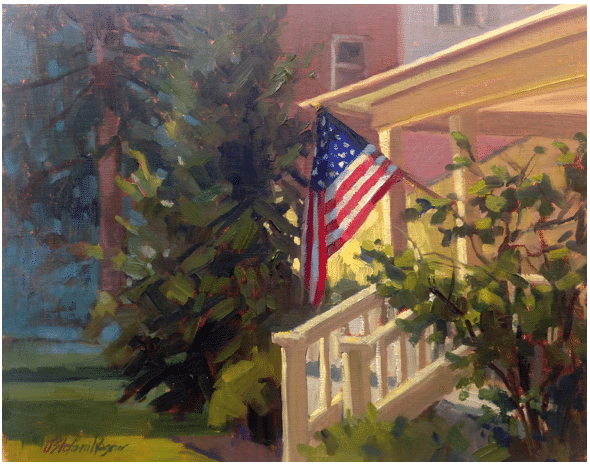

Jill Wagner, “Flagged”

“I love painting the many flags that fly in our community near Independence Day because they make exciting focal points,” says Jill Wagner. “But more importantly, they are visual reminders of how lucky we are to live in this great country… and that is definitely worth capturing on canvas!”

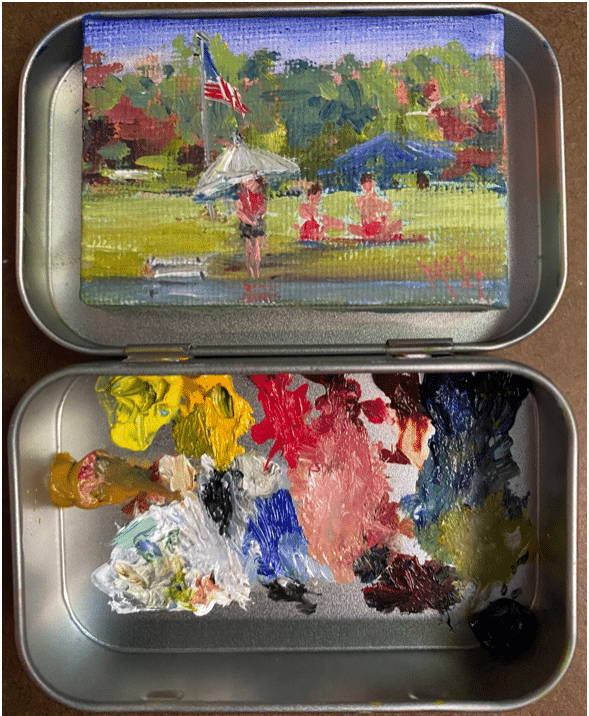

Bonnie McGown’s mini setup and Fourth of July painting

“I really enjoy daily painting,” says Bonnie McGown. “I saw a little painting online done in an Altoid tin and I thought it would be perfect for me. I ordered tins and little 2 x 3-inch canvases and started painting these little glimpses of my world. What fun! I sold one right away, I was hooked. This one was painted on the 4th of July this year. I went down to the lake in the morning, found my spot, and started painting. I was just finishing up and it started to rain. Closed up my little tin and I was done.”

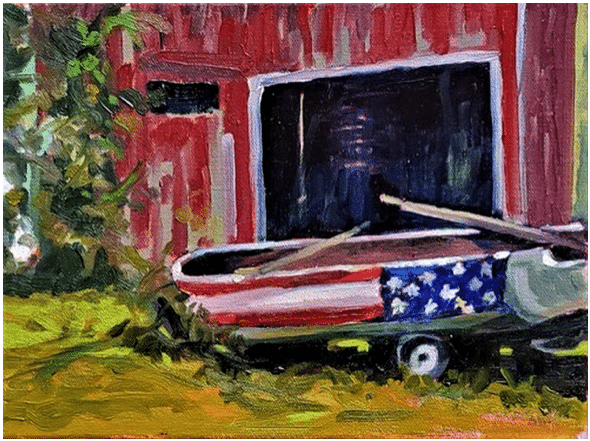

Tom Smith, “Glory Rests,” oil, 9 x 12 in., plein air

“Driving around looking for a subject in Plymouth, Wisconsin, I saw this view on a farm, screeched to a halt, and got permission to paint this amazing old boat,” says Tom Smith.

See more patriotic plein air paintings on this page.