Not long ago we compared equally innovative still life flower painters Eduard Manet and Henri Fantin-Latour: two 19th century French artists painting at close to the same time – 1882 – 1885 – with very different approaches.

We’re revisiting them this issue but with high-resolution closeups so you can see the wild differences in the brushwork.

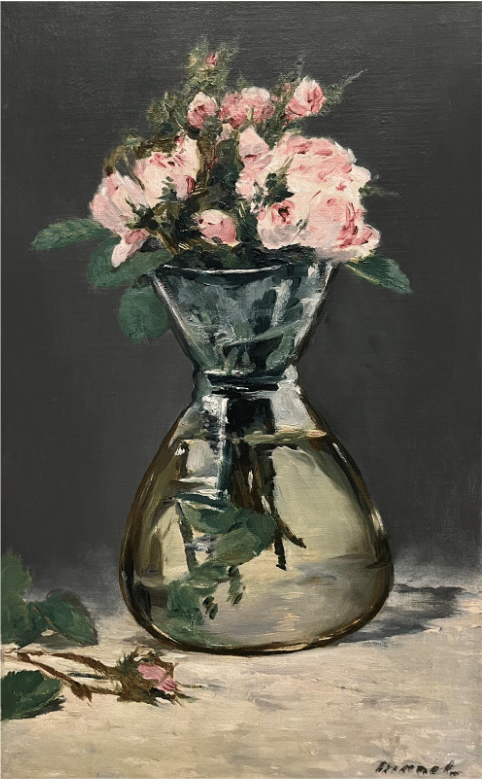

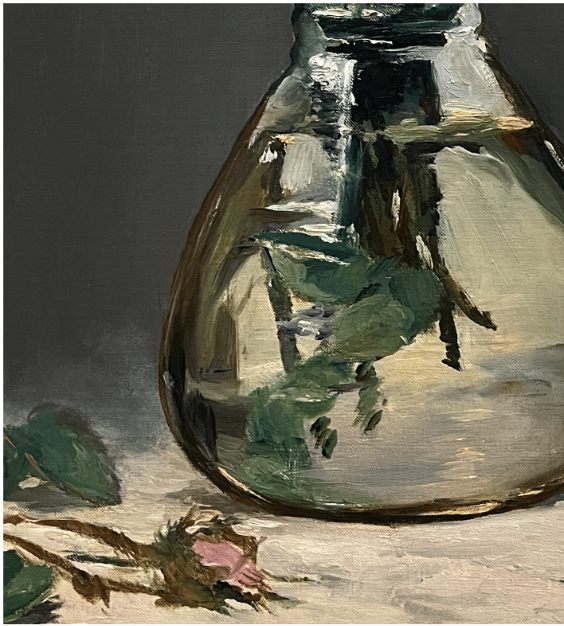

Edouard Manet, Moss Roses in a Vase, oil on canvas, 1882, approx.. 20” x 12”

Manet painted a series of small still lifes in his later years, when illness made working on a larger scale difficult. They’re remarkable for their cropped, apparent casualness of composition and confident paint-handling, which the artist uses to express a vision of art’s relationship to the world that’s strikingly modern, direct and free from over-sentimentalization. The light both shining through and reflecting off the surface of the vase gives a strongly concrete, unidealized feeling to the glass, which feels solid and weighty, in just a few big shapes and chunks of color.

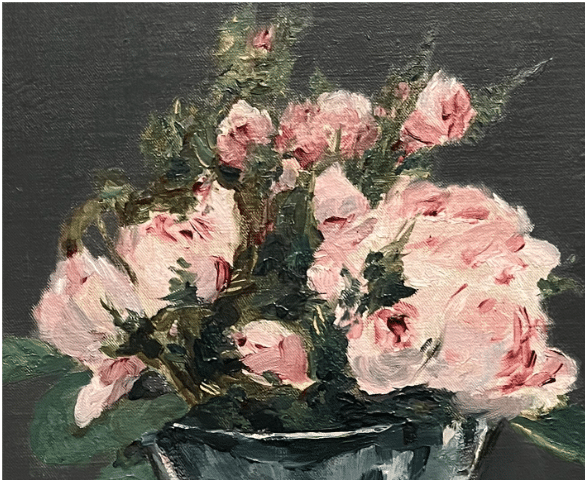

Manet paints the flowers and leaves in the image in quick strokes of color, calculated to suggest liveliness and motion. In this part of the painting, he expresses his feeling for the flowers’ freshness and life. He achieves this by again rejecting methodical, detailed rendering in favor of bright flourishes of lively color.

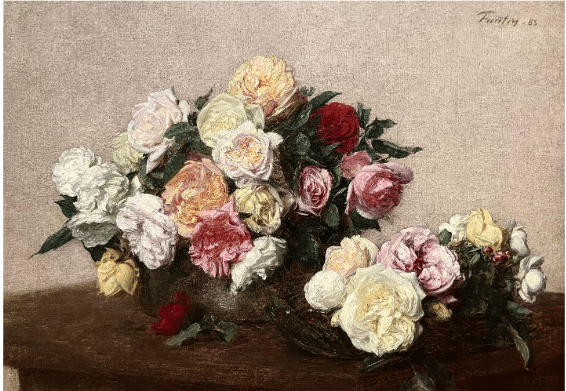

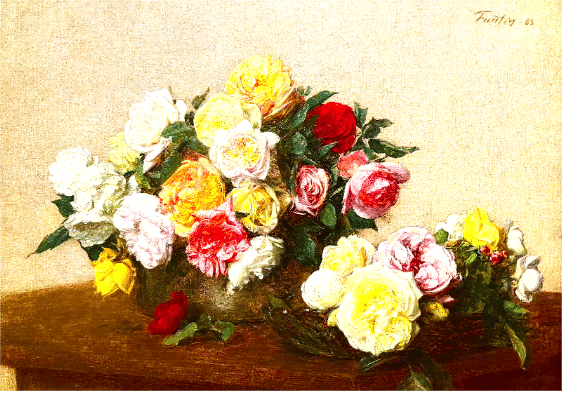

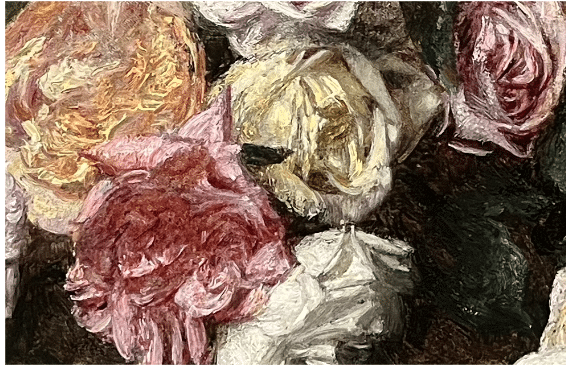

An entirely different effect appears in the roses of Fantin-Latour. Turning to Latour’s Roses in a Bowl and Dish, 1885, which is at the top of this page, we find something very different but in some ways equally compelling.

Like Manet’s roses, Latour’s blooms are rendered from life, and they look nothing like botanical illustrations and everything like artistic interpretation. In Latour’s work, some of this power must come from the composition. Latour arranges his roses in a series of elegant groupings based not only on color but on value, as you can see in this digitally manipulated “notan” image.

Doing the opposite – punching up the color intensity – reveals two major things.

One, there is a single red rose in the bouquet, which draws our eyes to its crowning glory – this one spot stands out as more intense and dramatic – and it has a color echo in the fallen blossom at the base of the bowl. Two, it displays how muted Latour’s color palette actually is in the original, and what a big part his subdued and subtle colors play in making this painting “work.”

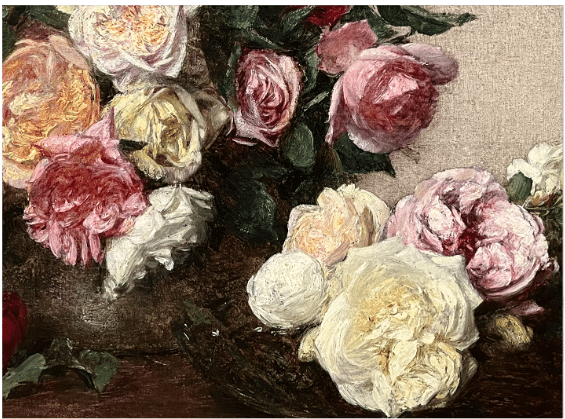

As you can see clearly here, Latour uses his brushstrokes in a more traditional way than Manet. His strokes follow the flowers’ forms, describing the contours of the petals, emphasizing dimensionality, highlights and shadows, natural shapes and folds.

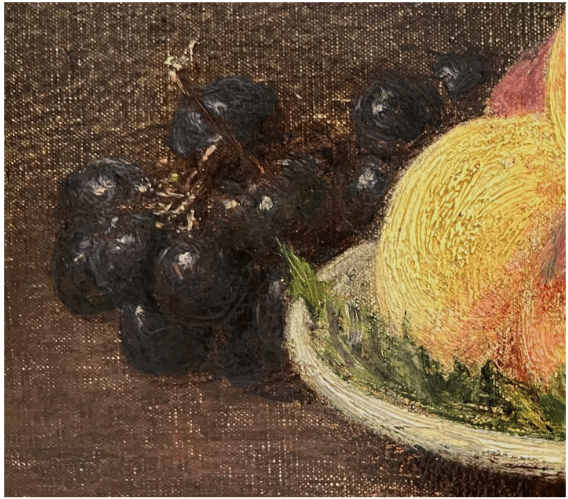

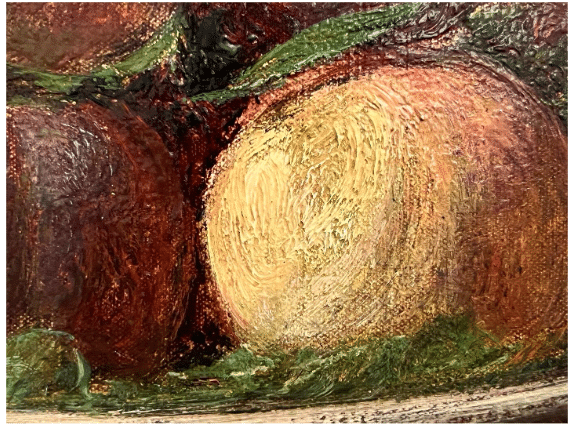

Latour’s greatest appeal is probably his mastery of those subdued color harmonies. He chooses and arranges his flowers based on the play of colors. In the still life below, we get very rich values and color relationships. In another departure from tradition, Latour uses his backgrounds primarily to support the color harmonies rather than to provide realism, context, depth, or perspective.

Further breaking from the norm, Latour used relatively large brushes for most of this work so as to ensure his brushstrokes remained strongly visible throughout. The strokes serve both to describe the surfaces and to suggest the solidity and the role of art in expressing the active life within.

So yes, these are observational paintings made from life designed to leave no doubt of their subject: plain peaches, grapes and roses. AND YET, as close-ups like these make it possible to see, these artists imbued their representations with their own visions through the paint handling itself. Putting the medium at the service of feeling and personal vision – what else is painting really all about?

Incidentally, this is why people say there’s no substitute for going to museums and seeing great paintings in person.

Take a Trip with Trippi

As you read this, Streamline’s publishers are leading a group through the greatest art to be seen within the great European art cities of Stockholm and Madrid. Fine Art Connoisseur magazine’s “Behind the Scenes” art trips view great works from a new perspective. Beyond excursions to museums, thee are visits with artists and iconic art experiences that leverage deep contacts in the art world. Guaranteed to create lifetime memories.

Hosted by Fine Art Connoisseur Publisher Eric Rhoads and Editor-in-Chief Peter Trippi, this is a continuation of an eleven-year tradition. Learn more here.

Ready to boost your still life skills? Check out one of the many instructional videos here.