The human need to examine itself in the mirror of art begins with early civilization, and portraiture is one of its classic and oldest forms.

As far as we can tell from history, the portrait begins in ancient Egypt, where men and women of many ranks, not just kings but also women, hunters, and even lowly craftsmen, were immortalized in sculpture and tomb paintings. Among the most striking examples of early portraiture are the Fayum mummy portraits.

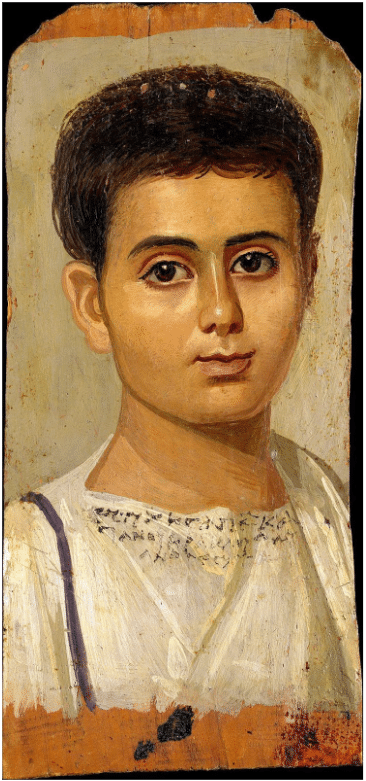

Fayum mummy portrait. Detail of a portrait mummy with its mummy wraps. Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was discovered by Flinders Petrie within a burial chamber in 1911.

These portraits covered the faces of bodies that were mummified for burial. They date from the period during which the imperial Roman Empire occupied Egypt, from the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD to somewhere around the middle of the 3rd century. They represent a marriage of Egypt’s funerary tradition of preserving images of the deceased in sealed tombs on one hand with the classical world’s practice of realist portraiture and panel painting on the other.

Portrait of a boy, identified by inscription as Eutyches (Greek: Ευτύχης), Metropolitan Museum of Art, made of encaustic on wood.

Amazingly, their colors are as vivid today as if they’d been painted last week. We owe the incredible preservation of the best examples to the darkness of the utterly still funerary chambers underground and the techniques of encaustic and animal-glue tempera, both of which seal pigments in an airtight medium. The following is from Wikipedia:

The majority of preserved mummy portraits were painted on boards or panels, made from different imported hardwoods, including oak, lime, sycamore, cedar, cypress and citrus. The wood was cut into thin rectangular panels sanded smooth.

The finished panels were set into the layers of wrapping that enclosed the body and were surrounded by bands of cloth, giving the effect of a window-like opening through which the face of the deceased could be seen. The painting’s accurate likeness of the individual, therefore, was of high importance.

This heavily gilt portrait was found in Antinoöpolis in winter 1905/06 by French Archaeologist Alfred Gayet and sold to the Egyptian Museum in Berlin in 1907.

The encaustic images show a striking contrast between vivid and rich colors, and comparatively large brushstrokes, producing something of an “Impressionistic” effect (as in the figure’s hair above). Other paintings done in animal glue tempera paintings have a finer gradation of tones but chalkier colors, giving a more restrained appearance. In some cases, such as the above, gold leaf was used to depict jewelry and wreaths.

The Fayum portraits reveal a wide range of painterly expertise and skill in presenting a lifelike appearance. The naturalism of the portraits is often revealed in knowledge of anatomic structure and in skilled modelling of the form by the use of light and shade, which gives an appearance of three-dimensionality to most of the figures. The graded flesh tones are enhanced with shadows and highlights indicative of directional lighting. Mummy portraits are represented in all important archaeological museums of the world

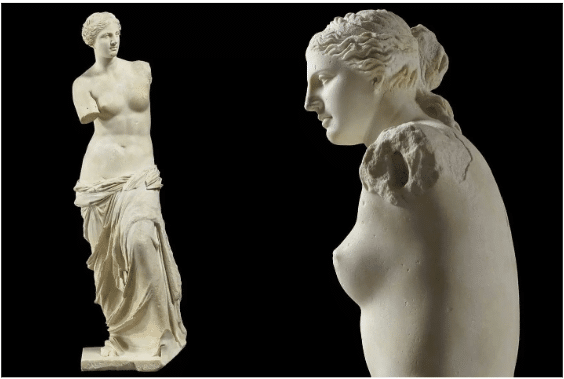

The Venus de Milo, photo © 2010 RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

However, it wasn’t painting but sculpture that provided the artists of the Renaissance with the “classical ideal” that became the benchmark for traditional Western portraiture. The dozens of Madonnas (also painted on wood panels) created by Italian painter Raphael, the contemporary and rival of Michelangelo, epitomizes the mastery of the ideal illustrated by the Venus de Milo, above.

Raphael, Madonna in the Meadow, oil on wood panel, 1505

We can draw a direct line spanning 400 years from Raphael to the French Academician William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905).

Bouguereau was the most significant leader of the Royal Academy of Art in France, which along with its equivalent in England, ruled as the most important and powerful professional art society in Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

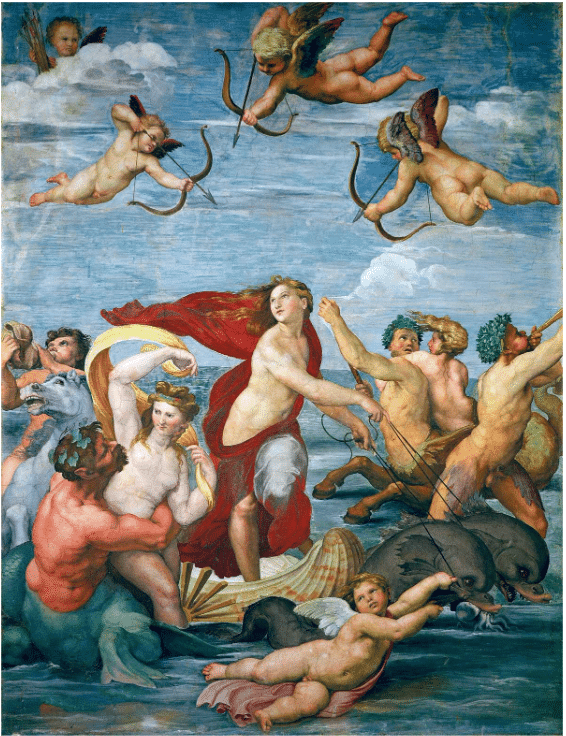

Raphael, The Triumph of Galatea, fresco (1505)

Bouguereau copied Raphael’s The Triumph of Galatea as part of his requirements for receiving the Prix de Rome. It seems Raphael above all others inspired Bouguereau with the ideal of the beautiful that he placed at the heart of his work.

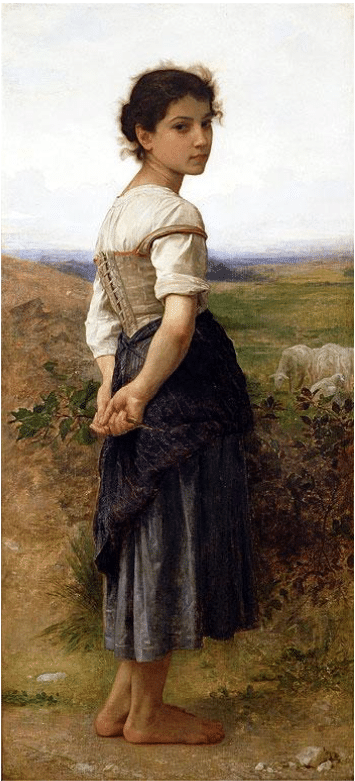

Bouguereau’s Young Shepherdess from 1885 (below) shows all the grace, poise, beauty, modesty, and elegant color, shading, and line handling we associate with classical portraiture, the immediate precedents for which were laid down by Renaissance masters such as Leonardo, Botticelli, Michelangelo, and of course Raphael.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Young Shepherdess, oil on canvas, 1885.

Bouguereau merged the revived classicism of the Renaissance painters with a sentimentalized subject matter. His formula proved so wildly popular with wealthy patrons in his time that it largely determined, through the powerful Academy he controlled, what art could and could not be exhibited and seen by the public in France. The Academy’s heavy-handed dominance in fact fired up the rebellious French movements that laid the foundations for modern art: first Barbizon (e.g. Corot), then Impressionism (e.g. Monet) and Post-Impressionism (e.g. Van Gogh), and finally Fauvism and early abstraction (Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso).

These opened the door for the many progressive and self-expressive movements that followed as the old world of the nineteenth century gave way to the new world of the twentieth.

Bouguereau today still gets far less attention than the Impressionists and all that came after. However, now that most of the dust has settled, it’s easier to appreciate just what a master Bouguereau really was in terms of oil technique at the service of visual poetry and nostalgic emotion.

Today, realist painters are looking again to Bouguereau as a the ultimate master of classical technique and teaching his methods to new realists through ateliers, workshops, and in videos on classical portraiture and style.