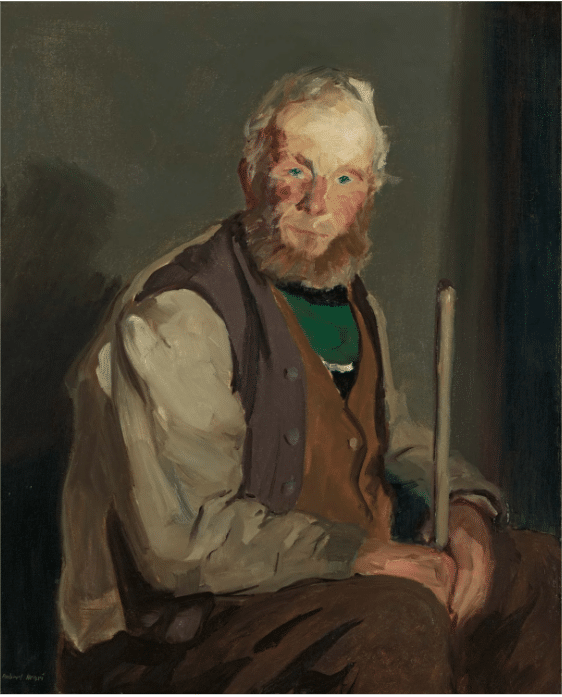

“There are moments in our lives, there are moments in a day, when we seem to see beyond the usual – to become clairvoyant,” wrote famous artist and teacher of the first years of the 20th century, Robert Henri. “We reach then into reality. Such are the moments of our greatest happiness. Such are the moments of our greatest wisdom.”

Henri is pointing to the everyday occurrence of sudden insights into the beauty or nature of our world, glimpses of greater meaning and happiness that most of us, harried by jobs, others’ needs, our own needs, and anxieties of every stripe, sadly are unable to fully grasp.

“It is in the nature of all people to have these experiences,” Henri said, “but in our time and under the conditions of our lives, it is only a rare few who are able to continue in the experience and find expression for it.”

Henri specialized in portraits, using a free, expressive approach to capture fresh visions of his subjects. To really sing, the portrait form demands, I think, something very like Henri’s moment of “clairvoyance” – insights (seeing from inside, from within) that we all experience but which only artists (in the broadest term) feel driven to express.

>> Mummy Portrait of a Woman (detail), A.D. 100–110, attributed to the Isidora Master. Encaustic on wood; gilt; linen, 18 7/8 × 14 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 81.AP.42

Portraiture is one of the oldest art forms, dating at least to ancient Egypt, where it flourished from about 3,000 BC. Portraits painted during the Roman occupation using the encaustic (hot bees wax) process, still look as fresh as the day the artist put down the brush.

But portraits have always been more than just a record. Usually those with enough wealth to commission one wanted to be shown a reflection of their own power, status, virtue, beauty, wealth, taste, learning or other elevated qualities.

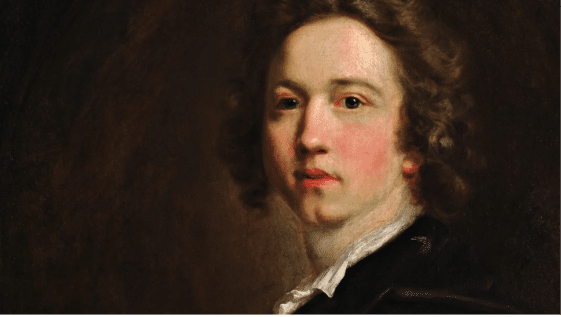

Sir Joshua Reynolds, detail from a self-portrait

English painter Joshua Reynolds invented European “high portraiture” by adapting the classical idealism of the Academy’s “Grand Manner” to the portrait form, according to London’s Tate Museum. This manner was characterized by direct, representational accuracy as well as the suppression of imperfection and the augmentation of “worthy” traits. The form did require on the part of the artist the ability to “see past” the surface to a “higher reality” based on the artist’s personal insight (or in Henri’s term, “clairvoyance”) into the nature of the sitter.

The French word clairvoyant means clear-seeing, bright-seeing, or “able to see clearly.” In English, the word carries the connotation of psychic ability. However, the artist also is called to perceive “things or events beyond normal sensory contact,” as one definition of clairvoyance has it.

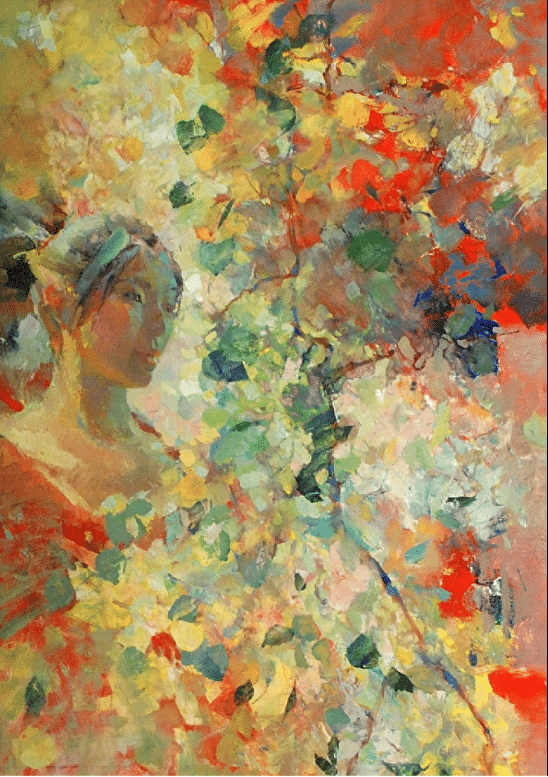

Kevin MacPherson, Seasons, oil 24” x 36”

An online French-English dictionary defines “clairvoyance” as “indicating or emphasizing truth,” which I love because it fits with the concept of seeing “beyond the usual,” reaching past the surface for insight into what’s real and true.

This is the magic of art – it expands the reach of imagination and insight. Art opens us to the moment we are living now and directs our attention to what’s meaningful. It’s all about play – playing with colors, shapes, and ideas.

Enough! Now, go out and play!

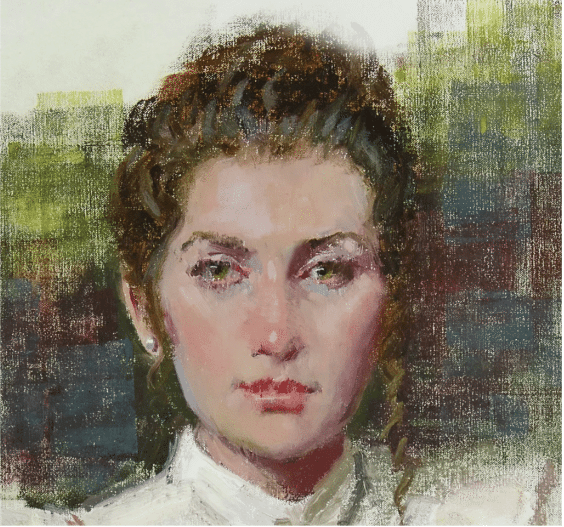

William A. Shneider, demonstrates how he made this expressive portrait in oil in his online video tutorial, Expressive Oil Portraits.

If a freely expressive approach to portraiture is of interest to you, William A. Schneider’s Expressive Oil Portraits may be just the thing.

However, if you’re interested in a more structured, classical foundation as in the traditions of Reynolds and other masters, then Kevin MacPherson’s video, The Magic Grid: Portraits may be more your thing.

What is Art Anyway?

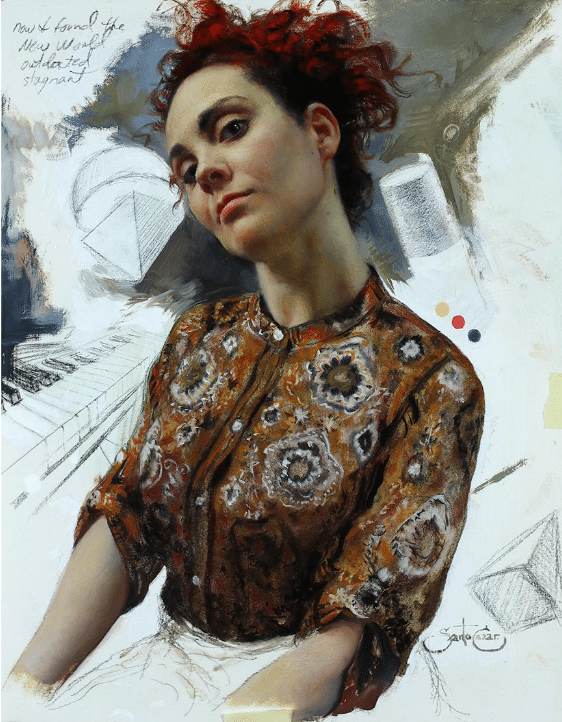

Cesar Santos, Page 35 Subject, 12” x 9” Santos teaches his methods in his downloadable video, Secrets of Portrait Painting.

Inspiration to create – is it not a universal human trait?

“I have no sympathy with the belief that art is the restricted province of those who paint, sculpt, make music and verse. I hope we will come to an understanding that the material used is only incidental, that there is artist in every man; and that to him the possibility of development and of expression and the happiness of creation is as much a right and as much a duty to himself, as to any of those who work in the especially ticketed ways.”

The desire to make art loops back to expressing one’s experience of a life touched by moments of vision, however quiet and however unassuming they may see to others.

“In every human being there is the artist, and whatever his activity, he has an equal chance with any to express the result of his growth and his contact with life,” Henri said “I don’t believe any real artist cares whether what he does is ‘art’ or not. Who, after all, knows what art is?”