More than 350 years after it was painted, Rembrandt van Rijn’s Woman Bathing in a Stream remains as intriguing as it did in 1654.

I have questions. Where is this so-called bathing taking place? The title tells us it’s a stream, but the overall vibe coming from the shadowy, cavernous background and the light (or lack of it) feels more like a still pool in an underground cave.

Scholars have long wondered and debated whether the image refers to a Biblical or mythological story as many of Rembrandt’s paintings do. No one can be sure. At any rate, this is no radiant nymph being spied on by a satyr.

She is rather, perhaps, Rembrandt’s mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels, or so speculate some (but not all) art historians . Rembrandt and Hendrickje, pregnant at the time, were living together but weren’t married. In 1654, the date inscribed on the painting, Hendrickje was summoned before the Reformed Church Council and confessed to “living in sin” with the artist, after which she was barred from Holy Communion.

Rembrandt, Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels, 1654. {{PD-US}}

In Rembrandt’s portrait of Hendrickje, painted the same year, she gazes out at us with a face curiously part girlish and part wise-woman, part playful and part tragic. It’s the kind of face you can’t quite read yet can’t look away from: all half-smiling lips, glowing cheeks, and limpid eyes, while shades of deep melancholy and unhappy resignation cross the expression like cloud shadows chasing each other across a meadow.

Contemporary artists such as Odd Nerdrum and artist-instructor Eric Johnson are direct heirs of Rembrandt’s dramatic lighting and subtle mysteries.

Woman Bathing, and the portrait of Hendrickje for that matter, give us that “intense, visceral hit” that art historian Simon Schama identifies as characteristic of Rembrandt’s late work. Some art historians see in Rembrandt’s late-in-life “intensity” a reflection of the artist’s downward-spiraling life and increasingly hard times.

Great Art – Bad Choices

It’s well known that Rembrandt’s personal life was a disaster. His first three children died within two months of each other along with his wife Saskia, who was only 29.

Rembrandt sought comfort with their surviving infant son’s nurse, Geertje Dircx. However, he dropped her in favor of an affair with Hendrickje, 20 years his junior, after she joined the household as Rembrandt’s maid.

Furious at such treatment, Geertje sued Rembrandt for breach of promise to marry, demanding regular maintenance payments. Rembrandt responded by having Geertje committed to a madhouse (few people in Rembrandt’s century had a nice word to say about this man’s personality or his behavior).

According to Saskia’s will, he couldn’t marry Hendrickje without losing his inheritance. But even with his late wife’s money, two years later Rembrandt was officially declared bankrupt. He lost his overly expensive house and moved, with Hendrickje and Titus, then 14, to a “low rent” part of town (that would be Amsterdam). Hendrickje successfully stepped into business as Rembrandt’s dealer, which is the only thing that kept the three from total destitution.

Vulnerability & Fancy Dress

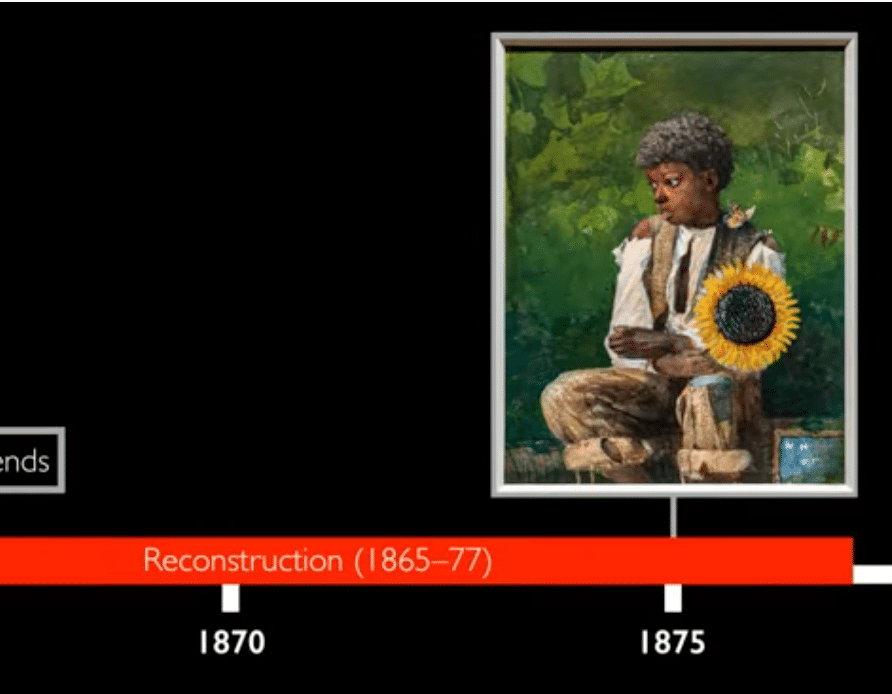

In Woman Bathing, the pile of clothing behind the figure suggests nobility of some kind; the fabric seems to be a combination of gold threading, brocade, and some sort of rich velvet or silk of an exotic cinnabar hue. Rembrandt loved fancy costumes and props and spent far too much money on tricking out his studio and dressing his models in them.

Rembrandt, A Boy in Fanciful Costume, 1633

A kind of sister painting to this one titled A Woman in Bed presents another partial nude in an ambiguous setting and pose. Painted the same year as the Bather, the woman in A Woman in Bed is draped in plain white bedclothes, amid a touch of the same kind of “fanciful” window dressing (gold tiara, “Oriental” bed curtains) Rembrandt loved painting into his pictures. It could be same woman, but we can’t be sure (at least one Rembrandt scholar contends it may be Dircx!).

A Woman in Bed (1645). National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. According to Gary Schwartz, the woman in the picture could be Dircx or Hendrickje Stoffels.

And of course it doesn’t really matter – Rembrandt’s Woman Bathing transcends portraiture. It’s about something bigger.

Nobility or not, the figure in Woman Bathing is everywoman, a stand-in for all of humanity. She’s depicted in simple, unflattering garments, having cast off any pomp or pretension. We can easily identify with her precariousness as she wades into the stream, Rembrandt’s genius guarantees it.

It’s not really about the woman he painted, or why, but how he painted her: It’s what he put into the painting, the way the figure stands out from all that looming shadow, at once frail and assured. Many count it among their favorite Rembrandts of all.

Although she radiates a definite sense of vulnerability, glowing pale amid the gloom, her expression is natural, almost one of pleasure or bemusement – but not quite.

Detail of Rembrandt’s Woman Bathing in a Stream

She’s looking down, presumably because she needs to watch her footing, and her face, as most of Rembrandt’s faces are, is half in shadow. It’s the figure’s strange mixture of humility, sensuality, strength and vulnerability that gives it something you only find in great art; it’s humble and evocative at the same time.

Slavery, War, and a Winslow Homer Watercolor

The Georgia Museum provides a lucent and inspiring analysis of a portrait that is so much more.

Hope you enjoy it.

– Chris