“I have learned more about painting through abstraction than I have in all my years as a realist painter,” says artist Larry Moore. “One method informs the other. It’s like a story with no ending.”

As even confirmed realists learn to at least understand abstraction, it’s being increasingly adopted as a tool like any other. Representational and non-representational abstraction alike have remained vital forms in contemporary painting, and abstraction continues to filter down as needed in subtle or not-so-subtle ways.

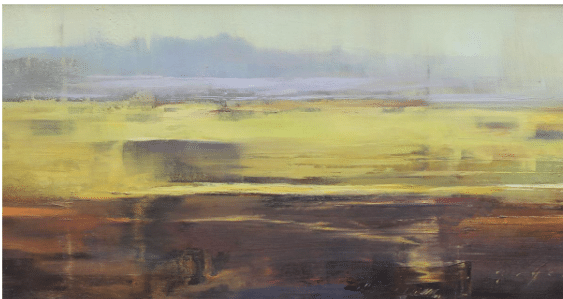

Douglas Fryer, “Farm on Highway 89,” oil on canvas

Artist Douglas Fryer invests his abstracted landscapes of rural America with an intimate sense of place. His atmospheric works combine gestural applications of paint, muted color tones, and abstraction with a sense of honest, lived experience rooted in the American west.

In “Farm on Highway 89” (above), the artist uses both atmosphere and gestural abstraction (produced by dragging a squeegee across the wet painting’s surface). By including the highway in the title, Fryer hints that we’re looking at the landscape in a blur, as if through the window of a speeding car. The result is an eerie and poetic suggestion of the speed of contemporary life, the way the rural past seems to recede all too quickly in the rearview mirror of busy, technological and industrial “progress.”

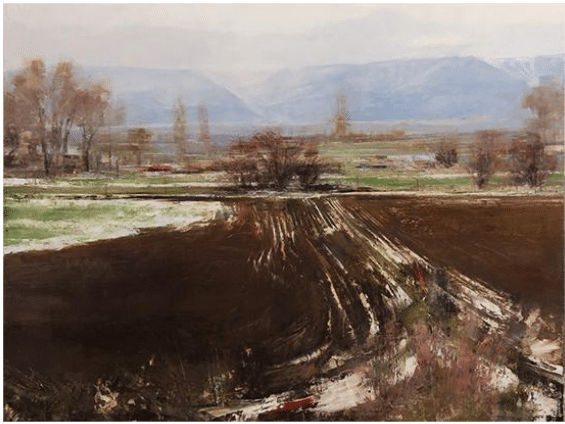

Douglas Fryer, Spring Thaw – North End, oil, 36 x 48″, Oil

There is in Fryer’s work a kind of poetry, related perhaps to what he has called “a reflection of what is true about ourselves and what we value most in our loneliest introspection.”

Douglas Fryer teaches his unorthodox approach to the tools and principles of traditional landscape painting in his teaching video, Painting with Intuition.

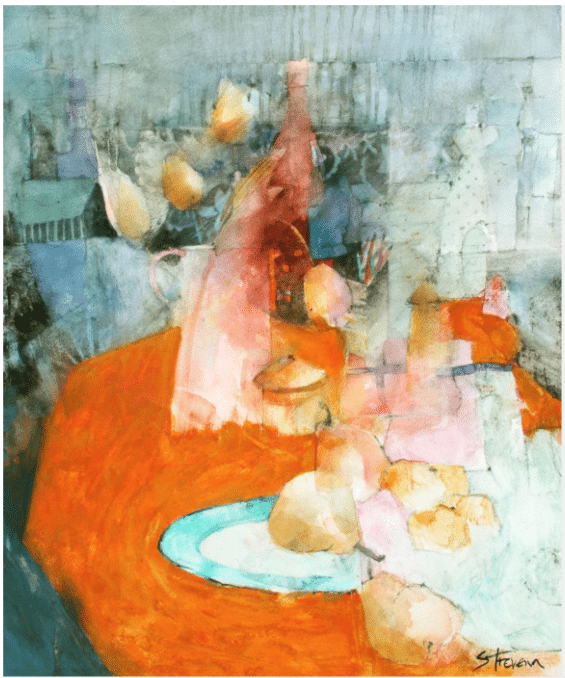

Another artist who uses abstraction in representational work is Shirley Trevena. Her still lifes are largely about sensation – they’re informed by how objects such as the colors of flowers in light and space can make us feel.

Shirley Trevena, Orange Cloth and Pink Jug, watercolor and graphite pencil, 45×38 centimeters.

Like Matisse, who was working from Cezanne, Shirley Trevena flattens and tilts the planes (such as the tabletop and pear angles) and plays with the rules of perspective to foster a freer and more playful interpretation of reality and an excitingly vibrant colorful surface.

Choose from three different teaching videos if you’d like to learn how Shirley makes her watercolors. Browse them here.

Artemisia Gentileschi Painting on View for First Time in Nearly 400 Years at Texas Museum

Artemisia Gentileschi, “Penitent Mary Magdalene,” 1625–26. KIMBELL ART MUSEUM

Artemisia Gentileschi (1597–1654 c.) was one of the most important and accomplished seventeenth-century Italian painters and also one of the most unjustly neglected by art history. As a woman, she faced terrible odds, including being sexually assaulted by her mentor. But she fought her way through to become a wealthy, successful artist sought after for religious, portrait and other commissions.

One of her impressive yet little known works has landed in Texas. The Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, recently acquired the Artemisia Gentileschi painting, “Penitent Mary Magdalene” from a private collection, where it “slept” for nearly 400 years. This month the Kimball is exhibiting the work, marking the first time the painting has been shown publicly since the 17th century, when Gentileschi painted it.

Gentileschi’s work has been prized by modern art historians for the way it presents women as strong and independent personalities with complex interior lives, something woefully absent from paintings by her contemporaries.

Penitent Mary Magdalene, which the Texas museum dubs “a masterpiece of the Italian Baroque period,” depicts a hunched-over Mary Magdalene with her eyes closed in a moment of introspection, if not exhaustion and defeat.

Mary Magdalene is shown as “penitent” because for the Italian Church at the time, Mary Magdalene was unjustly labeled a prostitute. In fact, the Biblical Gospels only identify Mary Magdalene as one of the women who travelled with Jesus and helped support his ministry “out of their resources,” indicating that she was probably wealthy.

She is said to have been a witness to the crucifixion, present at his burial, and to have been among the first to see the empty tomb. If anything, she should probably be seen more like Gentileschi has depicted her – if a persecuted woman at all, she is one who has turned away from a worldly life to a more spiritually devoted one.

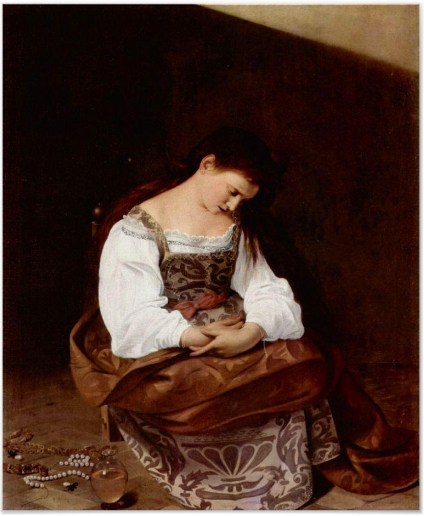

Caravaggio, Penitent Magdalene, oil on canvas, 48 x 38 in. (1594-1595)

Her better-known peer Caravaggio also painted Mary Magdalene with startling realism, dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, and use of live models. Both artists revisited the subject throughout their careers.