In a letter to Douglas Cooper in January 1955, Russian-French painter Nicolas de Staël wrote:

“True painting, always attempts to include all aspects, the impossible addition of the present, past and future.”

There’s a lot to unpack in that sentence! But what’s clear is that, although he’s seen as an abstract painter, de Staël was not just painting textures and abstract shapes in relation to each other – at the center of his work there is a lucid, wildly sensitive artist embracing life and committing himself to its expression.

We might say that the Agrigente series of paintings considered the height of de Staël’s career combine “present, past and future” in these three ways (in order):

- theme – the artist’s present-moment memory of a southern Italian summer

- motif – the architecture and heat at the ruins of the ancient city (and the whole previous history of European painting), and

- ideation – the way de Staël’s landscapes vanish into pure color and shape, the way all things past and present vanish into the immaterial world of the future.

Though his work is categorized as “lyrical abstraction,” de Staël in fact always denied being an “abstract artist”: “I do not set up abstract painting in opposition to figurative,” de Staël was careful to explain, “a painting should be both abstract and figurative: abstract to the extent that it is a flat surface, figurative to the extent that it is a representation of space.”

To understand de Staël, we need to ask Why choose this middle-ground between abstraction and figuration? I like to think it’s because it is just as much the essence of his experience as it was the essence of his physical subjects that he was after.

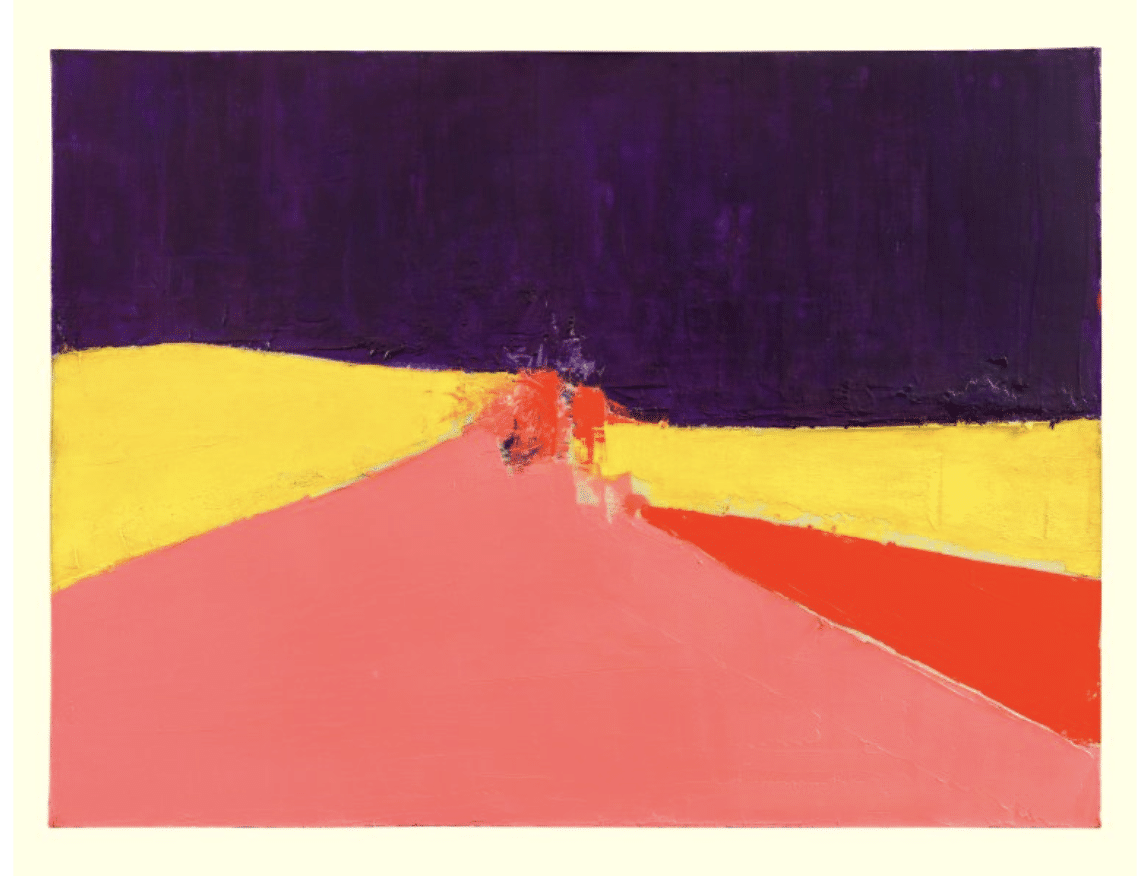

Nicolas de Staël, View of Agrigente, 34 1/2 x 50 3/4 in. 1954 Los Angeles MOCA

De Staël’s abstraction is “lyrical” (I would say poetic) because he was not interested in texture, color, or shape for their own sake. He was influenced by Cezanne, European Modernism, and Matisse, but he used their innovations to forge his own free expression. He loved representational painters, above all Velasquez, whom he named “the first unshakeable pillar of free painting.”

As critic and friend of the artist Douglas Cooper has explained, the miracle of de Staël’s work at its finest, was that he was somehow able to express “delight in what he saw, and the thrill of experiencing the thousand vibrations (to quote de Staël’s own expression) to which his volatile and sensitive nature was open.” Cezanne used the very same word, “vibrations” to describe the energy he felt in nature. De Staël wanted to free paint from representing the visible surface of nature so it could represent the inner energy.

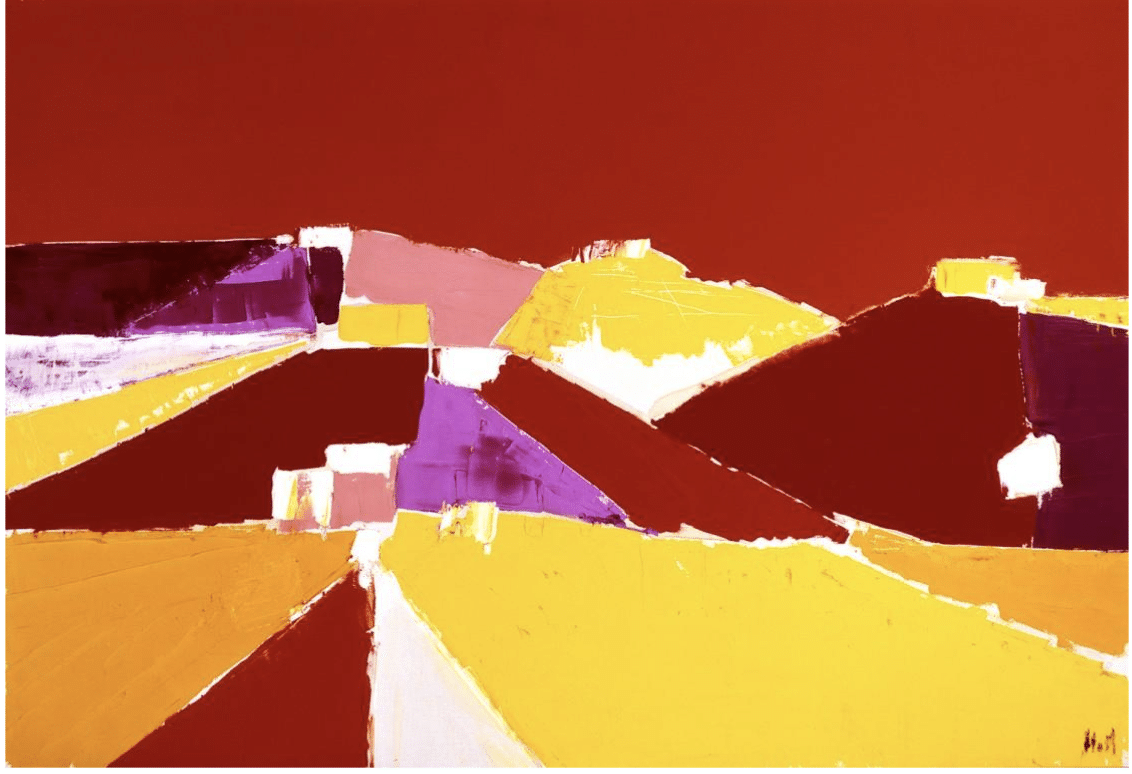

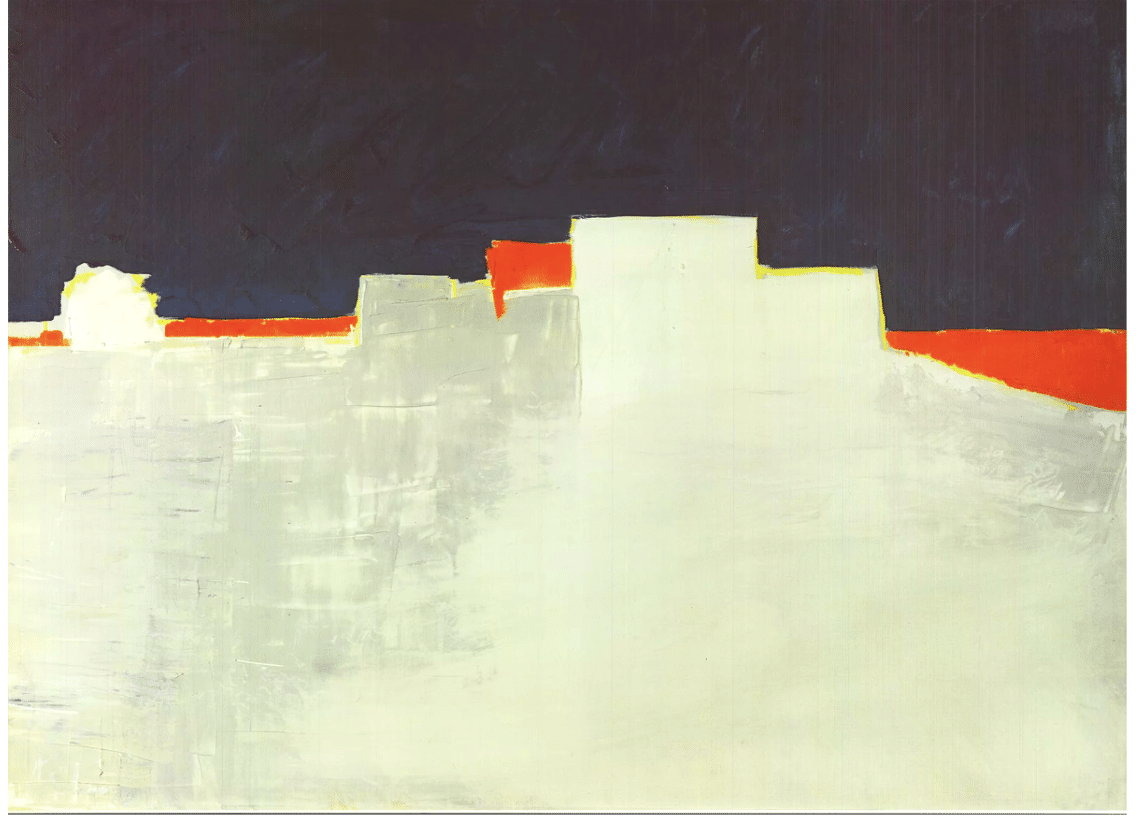

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente 2 (Agrigento is an ancient Greek city on the blazingly hot coat of southern Italy. Oil, approx. 30 x 50 in.

The Agrigente paintings were inspired by the raw and radiant Sicilian landscape he had seen and sketched around the ruins of the ancient Greek city of Agrigento in the summer of 1953. In Agrigente 2 (above), “the material nuances of form lie where the sweeping edge of one scraped mark meets or merges with the side of another,” according to an essay by Christie’s, “or where two vibrantly colored and intuitively-swept strokes articulate a jagged and electrifying strip of raw white light in the form of the bare primed canvas.” His work is often called “painterly” because of the way each abstract mark asserts a vitality of its own that speaks of the gestural act of painting while also adhering – just – to a representational function.

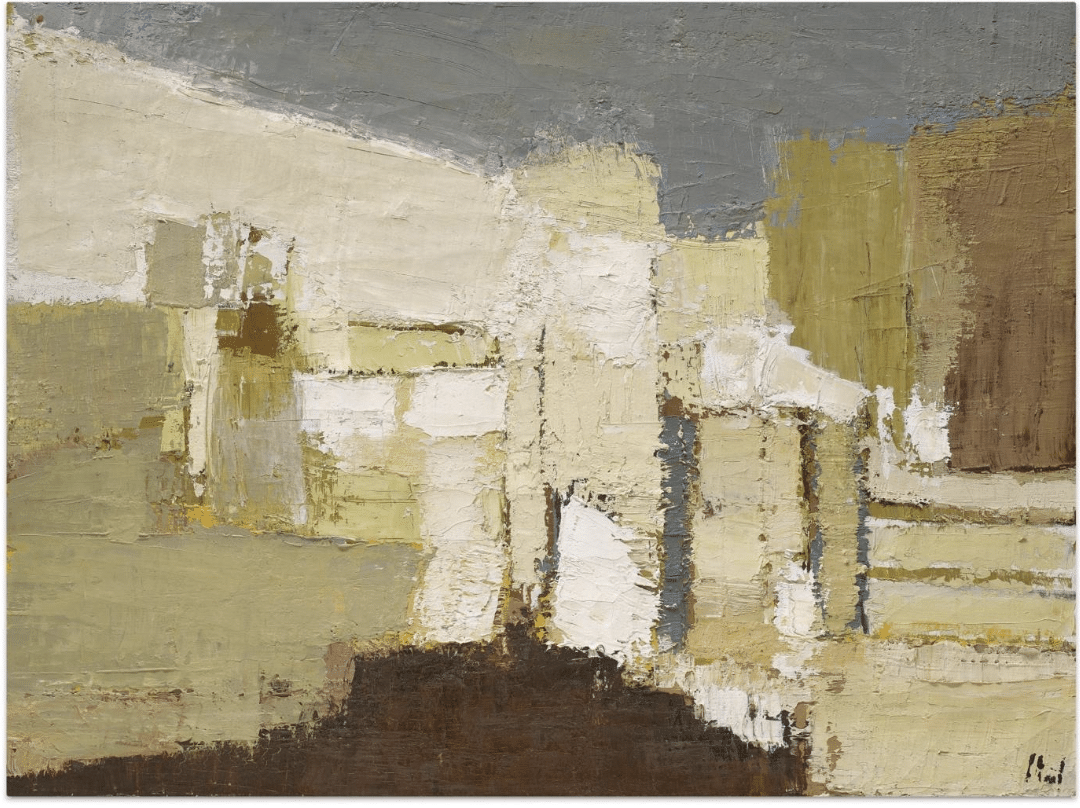

Nicolas de Staël, Landscape, Agrigente, 1953, approx.. 30 x 50 in. (A cool day among the stone buildings of the village, surely.)

De Staël used abstraction in the true sense of the word, as tool “to reduce down to the essence” of something. These are not formal exercises or paintings of nothing; his painting is never rhetorical or without resonance. De Staël’s color is a distillation of his sometimes exuberant, sometimes. melancholy feeling for life; his shapes are those of his surroundings, the things that delighted him in the cities, ports, and villages of eastern Europe, Spain, Italy, and southern and Mediterranean France.

His visual language consists of pure and vibrant colors, a few carefully chosen shapes, and subtle tonalities and textural boundaries – not for the formal or merely visual interest of doing so, but to convey an extraordinarily full visual experience – a heightened sensory involvement equal to his way of seeing and being in the world. Hovering on the very brink of abstraction freed him up to convey more about his experience of the subject than detailed representation would have allowed.

“I have tried to attain a freer form of expression,” he said, and his paintings were meant to connect with and convey. “I do not ‘objectify’ anything that I see. I do not paint before seeing. I am not looking for anything other than painting ‘visible’ by everyone.” He wanted to invite us into his way of seeing and being in the world.

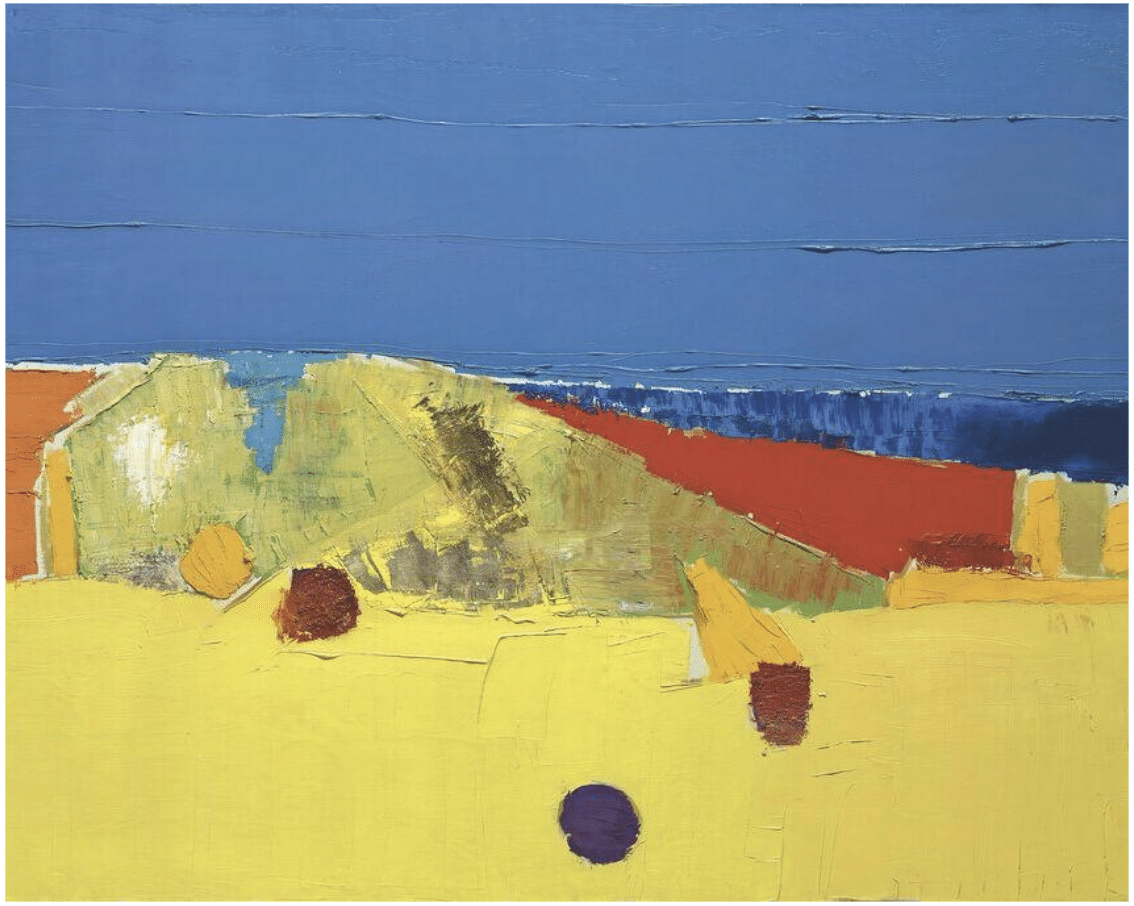

He wanted to be able to paint landscapes, the roofs of Paris, the sky at Honfleur, bottles, flowers, and apples. Dazzled by the light of the Mediterranean, he spent days on beaches painting brightly colored paintings, literally carving out his sensations through a daringly original personal visual language of palette-knifed, radically simplified yet earthy, textural forms. His rich impasto textures anchor these otherwise rarified, essential colors in the material world.

In the Agrigento series, as one historian has written: “de Staël’s Agrigente paintings fuse Mediterranean light with the Northern European landscape tradition, the rich colours and simplified forms of Russian icon painting with the dynamic colourism of Henri Matisse’s cut-outs.”

Agrigente, 1953

AGRIGENTO

A hot – blazing – sun-electrified landscape in relief against Mediterranean blue sky and sea – this painting, Agrigente (above) of 1953 was executed from memory in the warmth and light of Provence (southern France). This is a very pure form of painting, composed of dominating horizontal planes of cerulean blue and lemon yellow powerfully suggesting the artist’s sensations before a broad expanse of land and sky.

The motif: Ruined sixth-century Greek temple at Agrigento, Sicily. It definitely looks hot!

This vibrant and epic landscape sparked the painterly culmination of this artist’s unique adventure into the fusion of abstraction and figuration and made de Staël, at the height of his career in the 1950s, the most celebrated painter in Europe. For the artist, however, it was not a question of fame, but one of necessity. He did what he needed to do:

“All my life I have needed to think about painting,” he wrote for the catalogue of his 1953 show in New York. “to look at paintings, to make paintings to help myself live, to free myself from all the sensations, all the anxieties from which I have never found any other release than painting”

Now that’s hot!

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente painting, oil, 1953-1954.

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente painting, oil, 1953-1954.