We think of the “Old Masters” as a sedate bunch, circumspectly applying hard-won technique to noble and beautiful themes. But the 16th century Baroque genius Michelangelo Caravaggio, one of the greatest, was literally a gangster.

He showed up as a penniless street rat in Rome, and within five years he was so famously successful he’d spawned an entire movement of “Caravaggisti” who wanted to paint just like him. He’s gone down in art history as “the other Michelangelo.” Most of his commissions, too, were for churches, but that didn’t stop him from being a total “bad guy.”

He was suspected of affairs with his underage male models and purposely cast a notorious church-corner prostitute as the Virgin in a mural commissioned by the very same church she called headquarters. What’s wild is that this sort of thing was not a side-effect of an otherwise respectable career. Rather, it was an inseparable part of his profound influence, not just on art but on religion itself (at least in Europe).

It’s a bit of a paradox, but Caravaggio brought thousands into the piety of Christian belief. He was prone to random acts of violence; he was always on the verge of another knife fight, did things like shoving a plate of artichokes in a waiter’s face, and once punched a harmless cleric in the back for no reason. His hotheaded temper led him to the deadly attack of a rival fighting over the same prostitute. Consequently, he died young fleeing the international authorities because he was wanted for murder. He fell from grace as quickly as he’d rocketed to the top.

Caravaggio, Conversion of St. Paul on the Way to Damascus.

The Conversion of Saint Paul was painted at the beginning of Caravaggio’s fall from grace, reflecting his already disenfranchised view of the world around him. “He was painting what he was seeing as he was living it. For his fellow night [travelers] and the people who lived provisionally on the street, the inhabitants of the underworld, chiaroscuro, — the play of light and shadow — was not a painterly device but instead a necessary condition for survival,” said one art historian.

Caravaggio, The Taking of Christ

In The Taking of Christ (above), Caravaggio sets the 1 AD scene in contemporary Rome, with the unidealized faces of real people you might meet in actual life. The people “got it,” and the Church loved it. The Pope at the time was fighting growing criticism that the Church had gotten too rich, too decadent, and too out of touch, if not outright exploitative, of every day people (the roots of the Reformation).

Caravaggio’s paintings were the equivalents of big-budget movies (he practically invented dramatic “spotlight” lighting). By making it real – painting the risqué, worse-for-the-wear characters he knew from bars and street gangs as Saints and Biblical figures – the rabble of Rome, wrinkles, dirt, hangovers and all – Caravaggio’s work made those otherworldly parables and psalms suddenly very relevant and relatable. As far the all-powerful Roman Catholic Church was concerned, he was the perfect propagandist when they needed one most. And not only did he relish the role – he pushed its boundaries just to see when they’d break.

Caravaggio’s Narcissus, 1599

Caravaggio’s colors are never without meaning. His excessive use of saturated blood-red is the subject of writer Dian Parker’s piece, The Dark Red Drama of Caravaggio. Blood was never far from this artist’s life or the immortal pictures he heroically and uncompromisingly wrested from it.

Caravaggio, David with their Head of Goliath. It’s said he expressed his misery and perceived ill-treatment by painting his own self-portrait as Goliath’s decapitated head after being slain by David.

“Light and dark. Frozen action. Angels with dirty faces. Infamously both a hothead punk and one of the most extraordinarily potent and virtuosic painters in the canon, Caravaggio is nothing if not a man of contrasts.” – Lonely Planet has a no-holds barred free audio breakdown of Caravaggio’s 1607 The Crucifixion of St. Andrew.

Simon Schama did an excellent BBC piece on the artist. Also, check out these 21 facts about the C-man for a more thorough over and under.

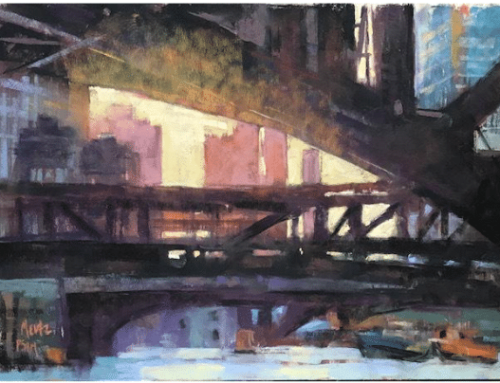

Going Rogue: Unconventional Subject Matter Wins Plein Air Prize

Richard Sneary took an unusual subject for his painting, Carrie Furnace #6. The rusted infrastructure of a closed industrial mill doesn’t spring immediately to mind when you think of plein air painting or landscape in general. Sneary’s treatment of the motif, however, brings as much beauty and fascination to it as any conventional approach. The watercolor took third place overall in the November Salon.

Plein Air Magazine’s monthly salon is an open competition that culminates in a lavish award gala with cash prizes for the best paintings overall in multiple categories. Visit the Plein Air Salon website for your chance to enter your work, from which the finalists for the grand prizes will be drawn.