Dutch artists painted on two levels, the visible and the invisible.

In their masterpieces we see gorgeous, sweeping vistas, stalwart windmills and masterful treatments of luxury tableware, where they saw “humble” wealth, abundance, Godliness and national pride. Dutch oils are in a sense paintings within paintings, thanks to the underlying symbolism that resonated for their original audiences if not always for us.

“There’s no one in art for finger wagging quite like the Dutch,” says British historian and author Simon Schama in his BBC Power of Art segment on Rembrandt van Rijn. During the Dutch Golden Age during the 16th and 17th centuries, the Netherlands were among the most powerful and prosperous nations in the world, a global leader in trade, science, art and military (naval) strength. But the very Protestant work ethic that helped propel them to dizzying heights of materialistic attainment also demanded they live a Godly life of modesty, thrift, and spotless moral fiber.

Every Sunday the ministers in their proliferating tall-spired churches stressed piety, humility, and the peril of losing one’s immortal soul to the demon Vanity. And so the art of the Northern Renaissance had to serve a dual purpose. The newly wealthy Dutch merchant class wanted to fill their townhouses and country estates with art that flattered their self-image and reflected their worldly success – but they wanted to look humble and pious while doing it.

Jacob van Ruisdael painted the landscape titled Wheat Fields in 1670, at the height of Dutch prosperity. A glimpse of tiny boats at sea on the far left provides

Detail from Ruisdael’s Wheat Fields showing distant commercial shipping vessels

a hint – but only a hint! – intended to reference the unrivaled strength of Dutch shipping and its dominance of the maritime trade routes over which Dutch goods, presumably including wheat, could be shipped abroad. This would have been painted as a commission for the merchant who owned these fields. Giving so much space to the sky in this painting does two things; it imparts a feeling of grandeur and nobility to what after all is commercial farmland, and it manages to showcase the cultivated fields that stretch (humbly by contrast) below the vast dome of heaven above.

Painted at about the same time, The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede also contains a coded message. To the Dutch, the windmill was a symbol of their ingenuity and triumph over adversity. Beginning in the medieval period, the vertical windmill refined in northern Europe reclaimed Holland’s disappearing land mass from encroaching nature, pumping water out of the lowlands and back into the rivers beyond the dikes so that the land could be farmed.

Ruisdael uses perspective and composition to ensure the windmill in his painting is the tallest, most illuminated and grandest thing in it, dwarfing everything else. This windmill, touched by the light streaming through a break in the clouds and presiding conspicuously over a dike in the foreground, flies the proud colors of patriotism without waving a single flag.

Ruisdael, The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, c. 1670

Other painters less eager to please their lucrative commission patrons, including Rembrandt, might have chosen a different vantage point, one that embedded the windmill as a distinctive but far less heroic feature of the landscape.

Rembrandt, The Mill, c. 1670

The Dutch “vanitas” still life did the same subtle two-step, allowing the wealthy elite to pat themselves on their well-clothed backs while congratulating themselves for being good Christians mindful of not storing up the soul’s treasures on earth.

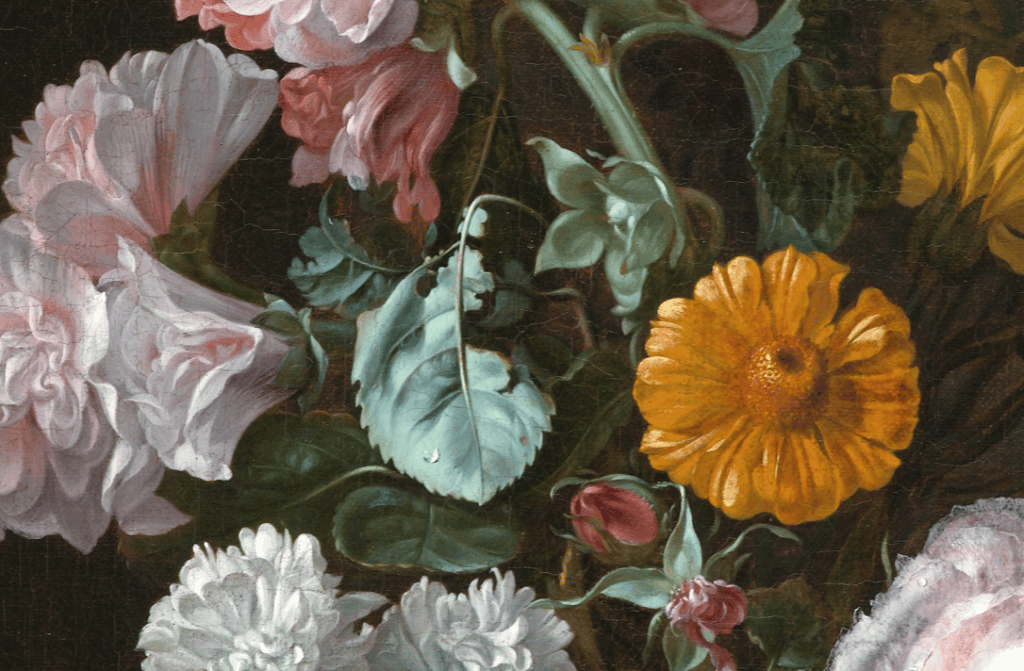

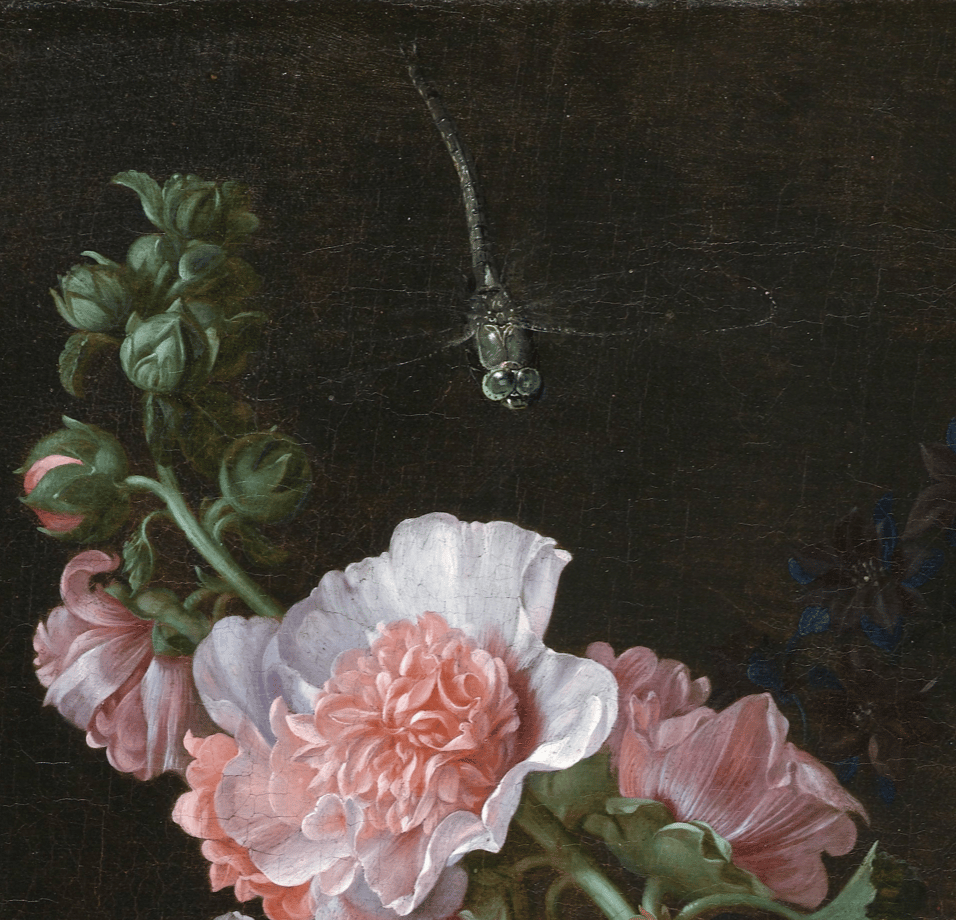

The typical Dutch still life looks at first like a painterly tour de force, created to showcase the artist’s skill at depicting a wide assortment of organic and inorganic shapes, colors, and textures.

Willem van Aelst, Vanitas Still Life, 1656

But look closely and you see the subtle signs of decay in the chewed leaf, the torn or missing petal, the insects and rodents almost invisibly fouling the perfection like William Blake’s “sick worm” that “flies in the night,” whose “dark secret love” invisibly destroys the heart of the rose.

The point? “All is vanity, sayeth the preacher.” These paintings are testaments to their buyers’ wealth and refined tastes – and they also do double duty as sermons on the theme of memento mori (remember you must die) and the vanity of human desires and perishability of earthly possessions.

The double-edged meaning? You can’t take it with you – but as long as you remember that, who says you can’t have it all?

The First Art Heist

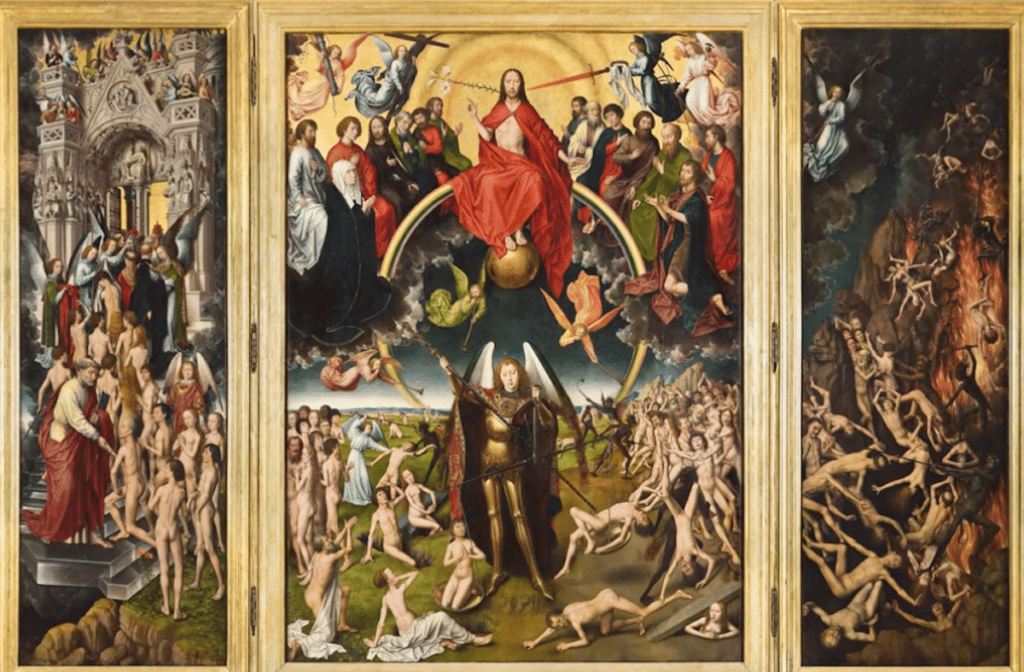

Hans Memling’s 1476 triptych, stolen while en route to Florence

In the first recorded theft of art in history, pirates boarded a 15th century merchant ship and got away with Hans Memling’s amazing 1476 three-part altarpiece, intended for a church in Florence. The pirates were Polish, and they took the painting back to their homeland, where it still resides, despite the protestations of the Italians who say they bought it fair and square.

For more, you could do worse than watch this YouTube Video on the Ten greatest art heists in history.

In the Paint,

Chris