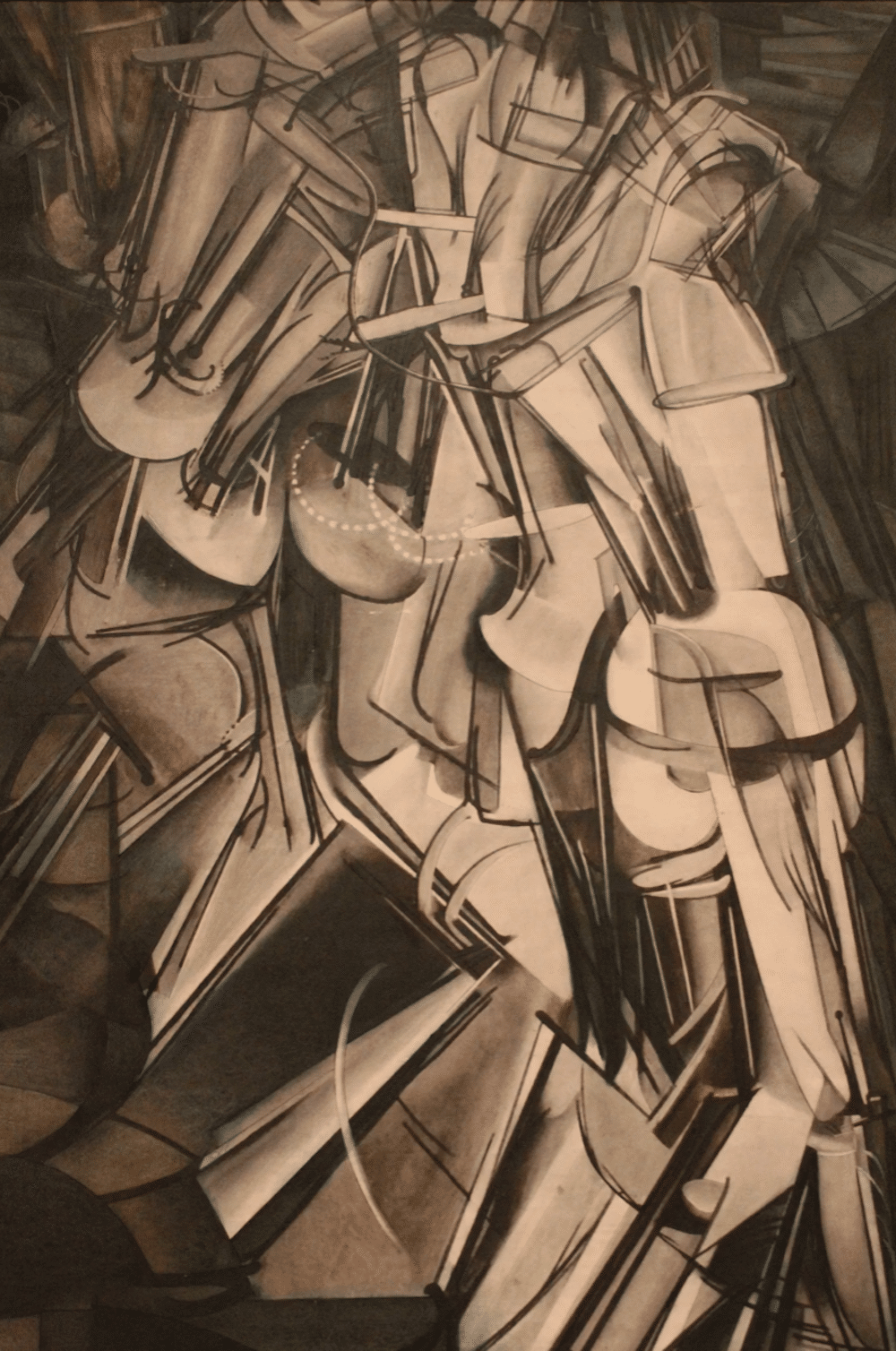

Marcel Duchamps’ painting Nude Descending a Staircase #2 signaled the convergence of traditional European painting and the mechanized, syncopated blur of modern 20th century life.

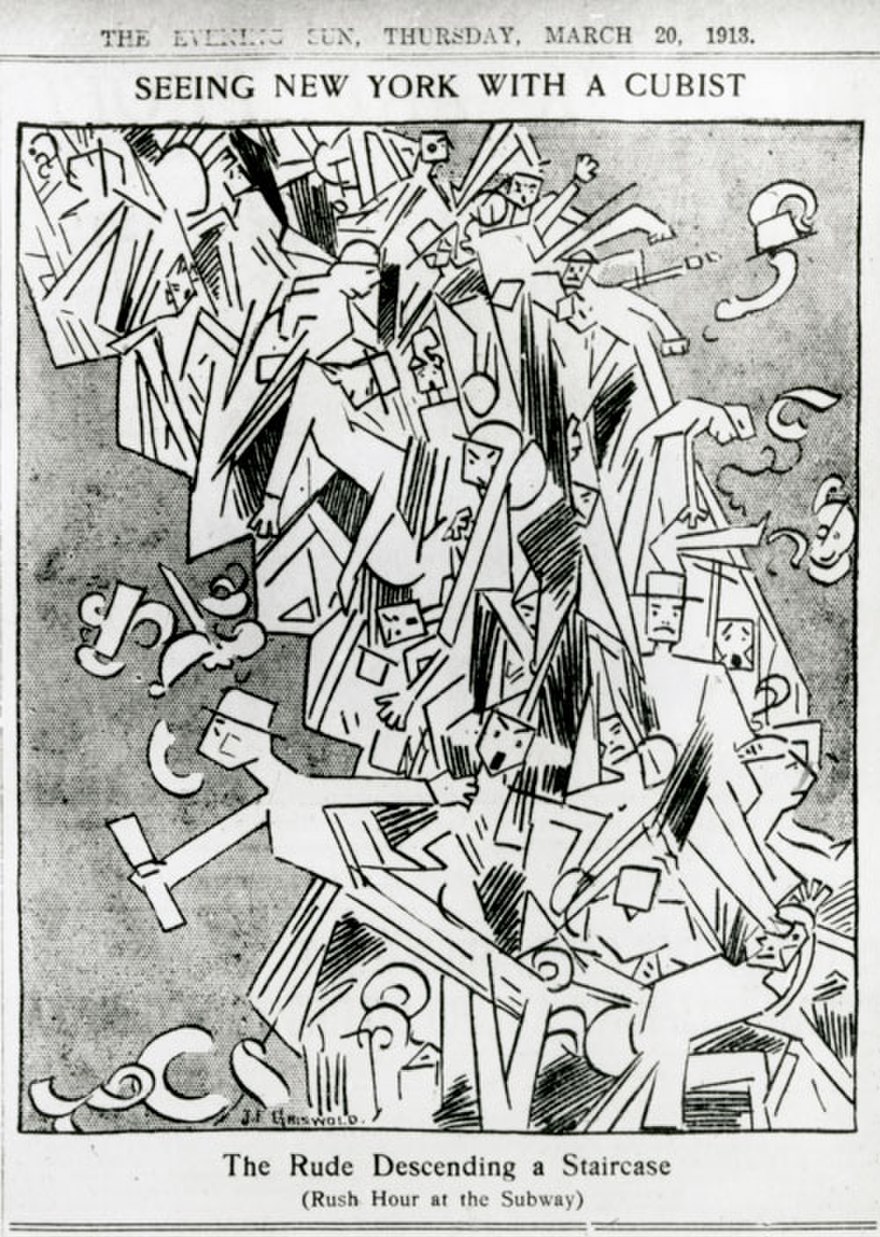

Americans first saw it at the 1913 Armory Show, a traveling exhibition that introduced “the shock of the new” (i.e. European modernism, including abstraction) to New York, Boston, and Chicago. It set in motion developments that escalated in visual art for decades.

Duchamp’s painting took inspiration from early cinema and motion picture photography as well as two new art movements, Futurism (an Italian style focused on technology and machinery) and Cubism, pioneered the year earlier (1907) by Picasso and Braque. His figure seems at once mechanical and alive, frozen and likely to move in more than one direction – perhaps upward AND down – at the same time.

Duchamp was doing with time what the Cubists had done with space.

Cubism – a detail from a painting by Picasso depicting a violin

The Cubists, rather than either trying to express their inner feelings or record their outer impressions, took a detached and analytical attitude to the traditional subjects of painting. As if to drive home their fractured view of modern life, they depicted familiar objects and figures unfamiliarly, from multiple angles at the same time. They presented their portraits and still lifes partly in a flattened, 2-D format, like blueprints, and partly in three dimensions, as if reflected in a broken mirror.

Duchamp’s painting shocked the critics. One wrote that it resembled nothing so much as “an explosion in a shingle factory,” a comment that the Frenchman probably wouldn’t have minded.

Mainstream America laughed it all off. (There are numerous animations and adaptations of Duchamp’s idea on YouTube, by the way. Some rise to the level of serious art, others not so much.)

But the American artists of the younger generation were frantically taking notes. The Armory Show planted seeds that would blossom fully a few decades years later, when New York stole Paris’ mantle and became, for the rest of the century, the global capital of contemporary art.

Nude Descending a Staircase, X. J. Kennedy (1961)

For me, this poem by X.J. Kennedy beautifully captures the painting’s balance between motion and poise.

Nude Descending a Staircase

Toe upon toe, a snowing flesh,

A gold of lemon, root and rind,

She sifts in sunlight down the stairs

With nothing on. Nor on her mind.

We spy beneath the banister

A constant thresh of thigh on thigh–

Her lips imprint the swinging air

That parts to let her parts go by.

One-woman waterfall, she wears

Her slow descent like a long cape

And pausing, on the final stair

Collects her motions into shape.

– X. J. Kennedy (1961)

Mountain Man: Asher B. Durand in the Adirondacks

Asher B. Durand, Adirondacks, 1848

Asher B. Durand is considered one of the “founding fathers” of American landscape painting. He was Thomas Cole’s patron, friend, and only student, and he inherited the mantle of leading American painter upon Cole’s death. As a young artist, Durand copied the old masters in the galleries of Europe and drew frequently outdoors. It was in London that a fellow ex-pat showed him the work of American landscapists John F. Kensett and Frederick Casilear, as well as, crucially, plein-air oil sketches by the late John Constable.

For Durand, the moment was life-changing. As soon as he got back to America, it was out to the woods, fields, and mountains in search of the “simple truth and naturalness” that he saw in Constable’s sketches. The region is still a beautiful prime painting location; Eric Rhoads, publisher of Plein Air magazine hosts an annual week of plein air painting there every summer.

Durand’s summer and autumn trips into the hills along the Hudson River led him to venture to the Adirondacks, where he painted the above landscape. As was the norm then, he sketched in pencil and oil directly from nature and created larger, more vivid compositions in the studio. And yet Durand’s Adirondack, Catskill, and New England landscapes, especially his woodland interiors, stunned contemporaries with a degree of fidelity to natural detail hardly if ever until then seen in North American painting.

Asher B. Durand, Woodland Interior, 1885