There are only three essential things to know about the “main center of interest” that every painting is supposed to have. (Or four, if you want to count my opinion that not every painting has to have one, but that’s another post.)

A painting’s main center of interest is an area the artist calls out distinctly from everything else. Artists tend to use “point of interest” and “focal point” interchangeably, but I think the latter is actually the better term. With focal point, you get a visual metaphor (camera lens) that even hints at the techniques involved, as we’ll see below. Also, in keeping with the camera-lens metaphor, there’s only ONE focal point per “shot,” as opposed to potentially several points of interest, main or otherwise.

The focal point’s job is not, as some believe, to make a painting “pop.” Simply including a few areas of significant light-dark and/or color contrast will do for that. No, a good focal-does more than “call the eye”; it provides a unifying anchor for the overall composition. For that you need only know three things:

- where to put it

- how to do it

- and how to “turn it up.”

Taking it one step at a time:

- Most painters recommend placing your focal point NEAR (not necessarily ON) one of the four “power spots” in one of the “quadrants” where, if you drew three lines across and three lines up and down, the lines would converge – as in this painting by Michael Coleman. (Coleman teaches his techniques in video, btw) Note how the other major compositional elements fall more or less right in line with the grid.

Michael Coleman, Country Field – divisions and circle showing focal point

2. Besides placement, value contrast (light vs. dark) plays a big role here. Placing your painting’s darkest dark right next to your lightest light creates contrast that rivets attention. Above, the light tree trunk stands out against the dark structure – AND, just to the left, the very dark tree trunks contrast highly with the light blue atmospheric sky. That whole area becomes the focal point.

3. Enhancing that high value contrast, hard, clean edges make up the focal point’s final key component. Punch up the volume on the area of your lightest lights and your darkest darks by also giving us some of the hardest and cleanest edges in the picture. Above, just about every other place where dark meets light, the edges between them are softened, or somewhat lost. Again, the eye is drawn to sharp demarcations and areas of stark difference.

Watercolor artist Rickie Vios in this article breaks the technical process into four steps.

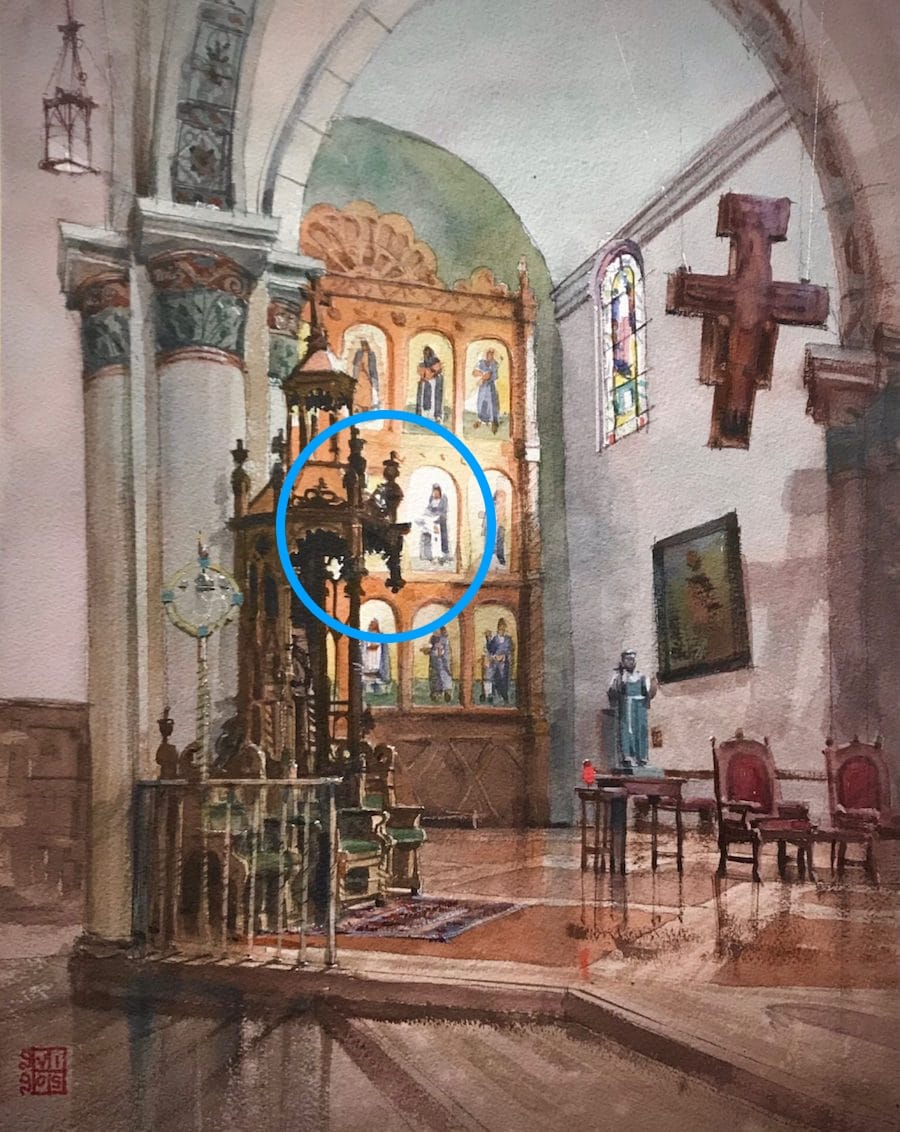

Rickie Vios, The Nave – Darkest dark nest to the lightest light with a hard edge between them

In Vios’ The Nave, the darkest darks touch the lightest lights with a hard, contrasty edge that stops the eye. That’s the focal point, and everything else falls into place below it in the hierarchy of where the eye goes first, second, etc. Vios taught at this year’s Plein Air Convention and Expo in New Mexico last week, and he has a number of instructional videos you can check out here.

Sunlight, and Shadow

Sunlight on the Coast , 1890, oil on canvas by Winslow Homer, American, 1836 – 1910. Tol e do Museum of Art, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbe

Winslow Homer’s 1890 oil painting Sunlight on the Coast is being shown as part of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art‘s exhibition, “At First Light: 200 Years of Maine Art.”

The painting’s crashing waves and slanted rocks edge anything like humanity out of the picture. Until you notice, that is, a tiny, frail fishing boat balanced on the giant swell in the top right corner. While this “point of interest” is not the main focal point (that’s the rock jutting up from the foam in the middle ground), if not for the contrast Homer builds in between the very dark ship’s hull and the silvery strip of light beneath it, we probably wouldn’t ever see it at all.

Homer’s sea is alternately tar-black and gun-metal gray, and the sky is an eerie neutral – rather dark for a painting titled “Sunlight on the Coast,” no?

In the paint,

– Chris

Art & War: Fighting the Cultural Assault

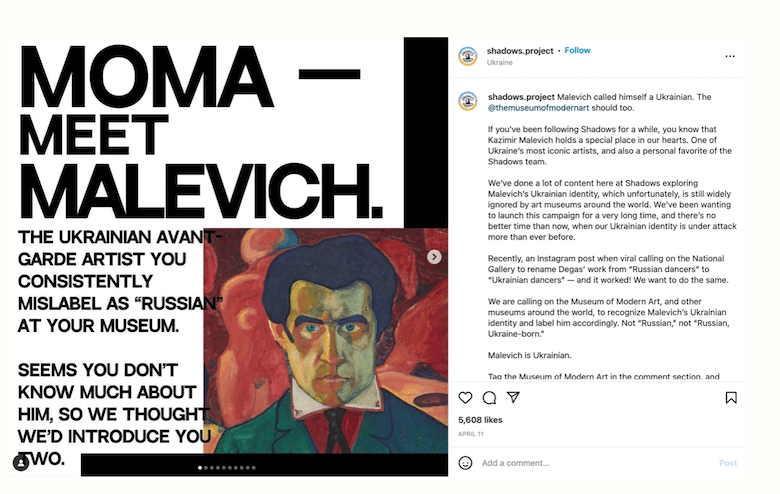

A major figure in the history of art, Kasimir Malevich is one of the most important painters of early twentieth-century modernism. His work still resonates with importance to contemporary modes of abstraction. Until now, most art history textbooks have considered him Russian. That is evidently in the process of changing.

Screenshot from Instagram

Through a digital initiative called The Shadows Project, a group of Ukrainian students are fighting back against what they perceive as Putin’s “cultural assault.” Part of that project is to establish Malevich’s nationality as Ukrainian. Although Malevich was born in 1876 in Kyiv, then part of the Russian Empire, in his diary he describes himself as Ukrainian. It’s only one manifestation of The Shadows Project’s push to get Western institutions to identify Ukrainian art and artists as such and thereby reclaim their culture.