Albert Bierstadt’s A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie, represents the heroic approach to painting mountains. At nearly 12 FEET across, Bierstadt paints the scene almost to scale, as if you’re there. He’s got us standing on a rise of ground in the lower righthand corner of this canvas, where we can plainly see the individual ferns, weeds, and pebbles at our feet. From there, the panorama stretches far and away, where sky and earth dissolve into each other, as a massive storm engulfs the range – note the high, Alps-like peak sunlit in the clouds rising above the roiling storm-clouds. When Bierstadt telescopes and magnifies the vast scale of the landscape like this, he ensures we feel something of the same awe he felt as an observer.

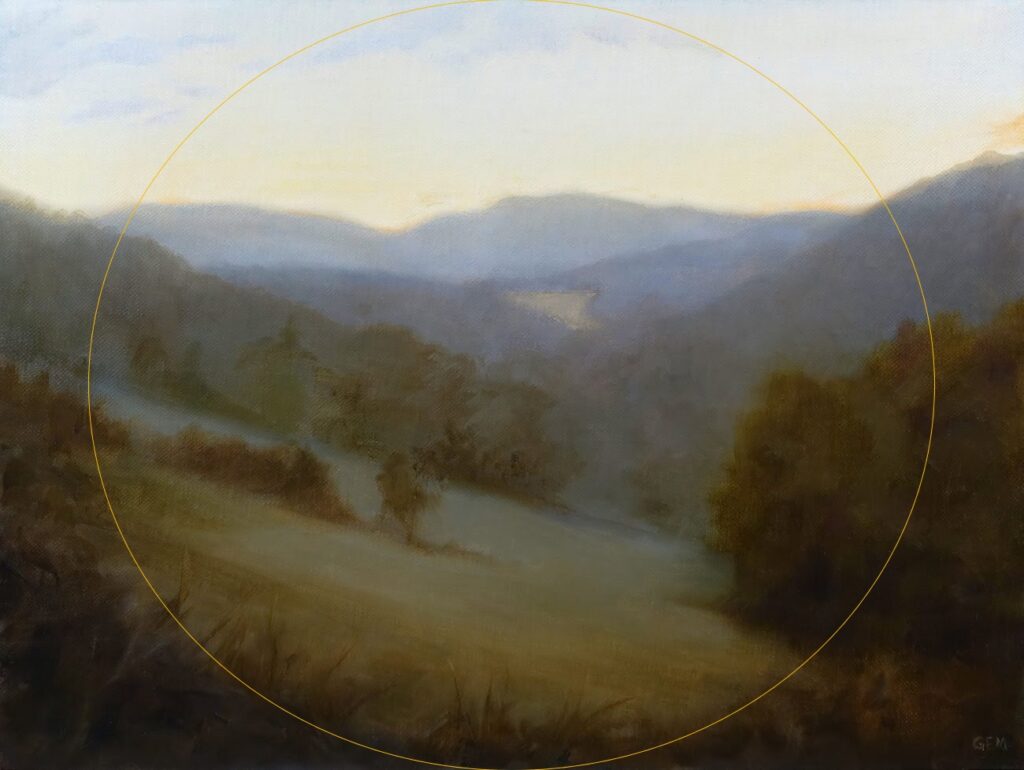

1. Valley – Mountain – Sky (Circular Composition)

Bierstadt’s composition is one of three basic choices you can make when faced with painting mountains. We could call this first approach the Valley – Mountain – Sky or “cosmic” arrangement – there’s a circular composition secretly at work here that encompasses and unites the earth and heavens. In the hands of a Romantic artist like Bierstadt, the tendency is toward an intermingling of the elements, a nearly mystical sense of the permeability and oneness of things within the awe-inspiring compass of Nature.

Vly Mountain,” 2022, oil, 9 x 12 in., Private collection, Plein air

Gayle Madeira’s Dusk on Vly Mountain (2022, oil, 9 x 12 in., Private collection, Plein air) takes the “Valley – Mountain – Sky” approach: roughly equal air time for the foreground valley, the middle ground mountain peaks, and the cloud-strewn sky (with attention to the compositional opportunities of the clouds to complement shapes and directional lines in the middle and foreground regions.) The axiomatic “rule of thirds” still applies though, with two-thirds given to earth and one to sky.

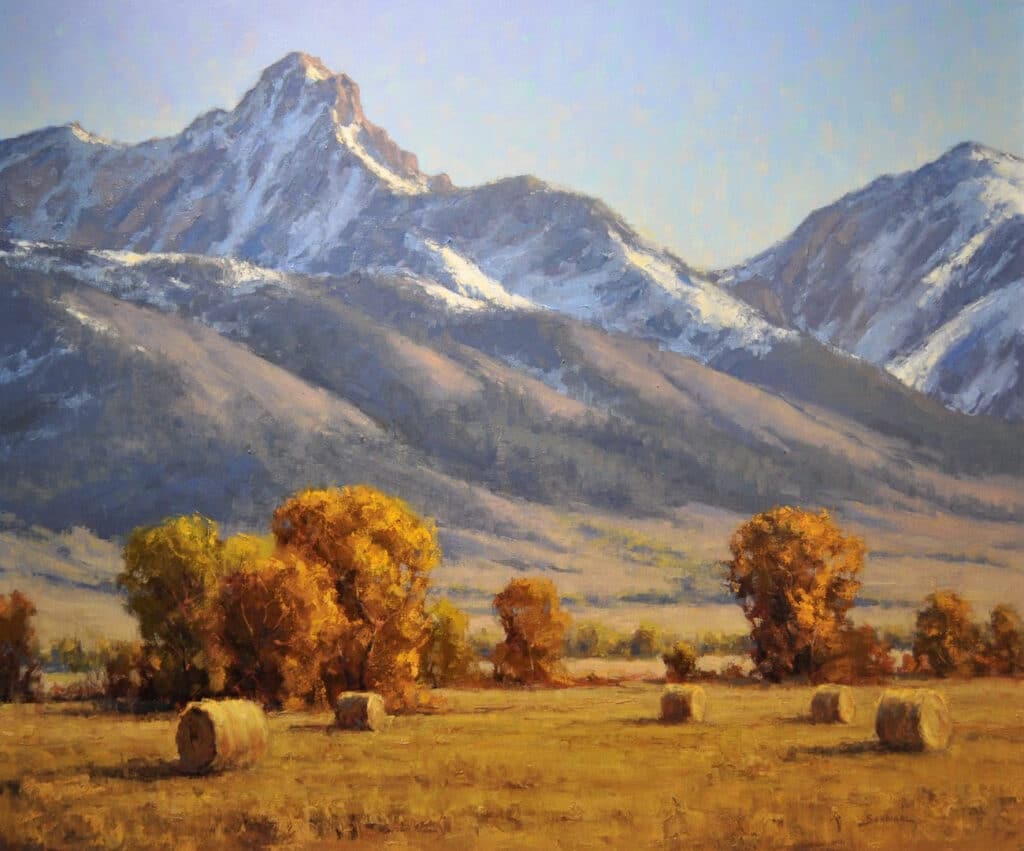

2. High Mountain, Low Valley

The “High Mountain, Low Valley” composition allocates two-thirds or three-quarters of the canvas to the mountains, and the remainder to a relatively flat foreground. This approach emphasizes the hight of the mountains as they rise over a relatively flat foreground plane in which the degree of detail is up to the artist.

Greg Scheibel, “Autumn in the Rockies,” 2022, oil, 27 x 33 in., Private collection, Studio from plein air studies

3. Distant Mountain, Close-up Ground

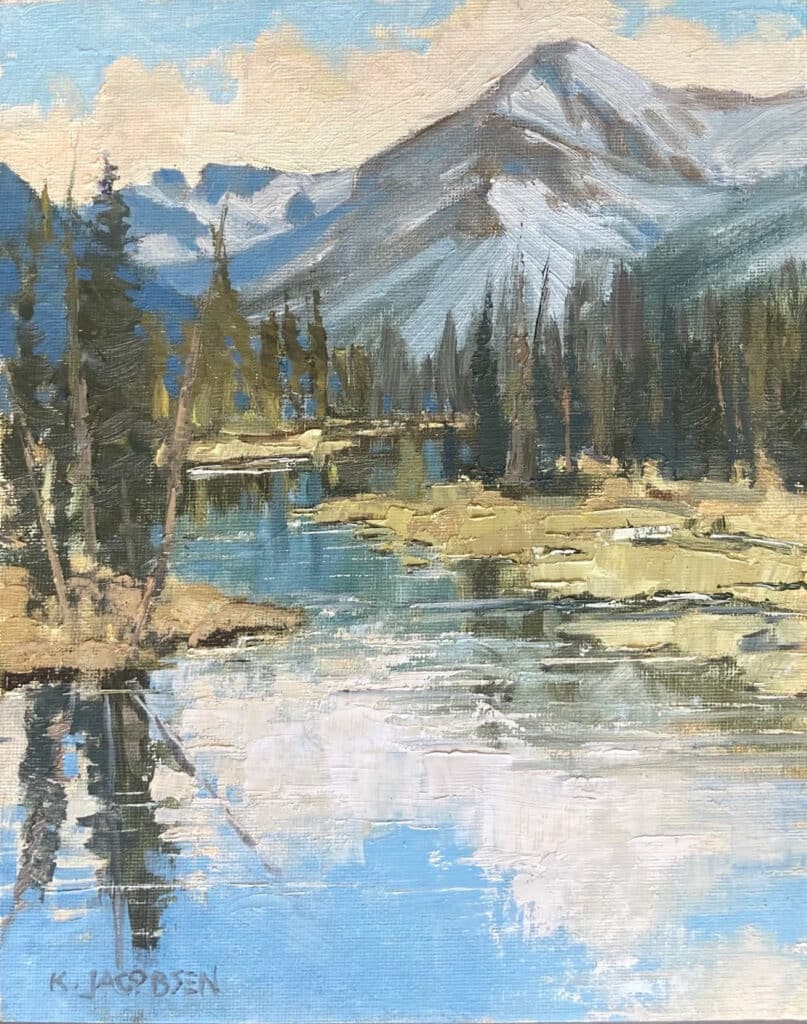

The final choice among these three is to give more space to the foreground and less to the mountains and sky.The effect of this compositional choice is to push the mountains further back in pictorial space and to spotlight features in the foreground, as Karen Jacobsen does with the river and its cloud reflections in Stanley Lake Outlet (2022, oil, 10 x 8 in., Private collection, Plein air), below.

Karen Jacobsen, “Stanley Lake Outlet,” 2022, oil, 10 x 8 in., Private collection, Plein air

Giving some thought to the composition before jumping in lets you call the shots. What are you going to emphasize so that it gets the lion’s share of the viewer’s attention? Breaking it down is a good way to go – give yourself three options: concentrate on things in the foreground (Distant Mountain, Close-up Ground), things in the middle-to-background (High Mountain, Low Valley), or all on equal terms (Valley-Mountain-Sky, circular composition).

If you’re looking for way to improve your own mountain paintings, look no further than this collection of high-quality, detailed instructional videos on painting mountains en plain air and in the studio.

Vermeer Mystery Solved

The Newly Restored Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window by Johannes Vermeer, 1652

When conservators finished a years-long process of restoring the painting known as Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window by Johannes Vermeer, what they found and presented to the world for the first time was a giant missing puzzle piece that put the work in a whole new light. They discovered the image of Cupid in a painting-within-a-painting behind the girl, a symbol that Vermeer himself had painted over. The conclusion? The Cupid refers to the letter being read by the girl – it is, of course, a love letter.

You can see the newly restored masterpiece (which had its own exhibition in Dresden in 2021-’22) in person the year in the largest Vermeer exhibition to date at the Rijksmuseum, from February 1o to June 4, 2023. This promises to be a show of historic importance. The last monographic exhibition on Vermeer was held 30 years ago in Washington, DC, and in The Hague.

Previous, unrestored version, as known to the world as Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

The Rijksmuseum hopes that this most ambitious Vermeer exhibition ever held will introduce this mysterious painter to new generations, “in a show encompassing Vermeer’s most prominent paintings from all around the world.” Having them all in one room, their museum states, should “help us (better) understand the artist’s technique, considerations, and decisions.” Not to be missed if you’re near the Netherlands this spring!