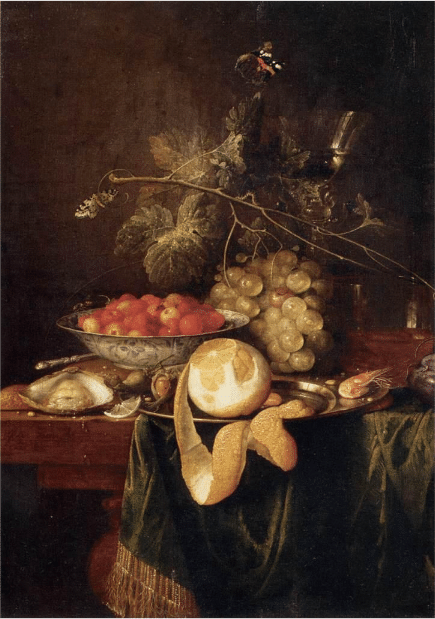

What a harvest is here in this still-life painting by the Flemish Baroque-period painter Jan Davidsz. de HEEM (1606-1684): a wooden table draped with a gold-fringed green velvet cloth, a glass of white wine and a cluster of white grapes hanging from a vine branch with large, veined leaves, a pewter dish supporting a peeled lemon, a cooked shrimp and a scattering of hazelnuts, behind which is a bowl full of cherries and, to the left, a shucked oyster, and behind that, the handle of a knife.

But the painting’s real essence is none of those things. Rather, it is this canvas’s somber atmosphere with its evocation of silence, luxury, stillness, and sensuous delight. The objects don’t so much sit or stand as emerge from the enveloping dark. And there’s much more to see than initially meets the eye.

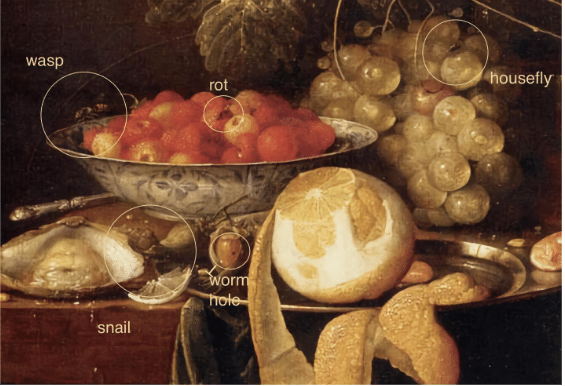

In the zoomed-in detail below, there’s a bouquet of “what’s wrong with this picture” details: There’s a snail slinking past the oyster, a wasp guarding the cherries (at least one of which is rotting). There’s a moth flitting by and housefly perched on one of the grapes.

DETAIL, Jan Davidsz. de HEEM, Still-life with Peeled Lemon, highlighting a few of the many symbolic critters (from l-r, moth, wasp, snail, and housefly).

What gives? Most still-life paintings of this time-period and geography contain a marvelous overlay of symbolic meanings. A kind of inside-joke or verbal riddle for original viewers who wished to read into them, each of the objects carried well-known associations accrued from their use in popular religious and moralist writings and sermons. To the sophisticated patrons of the time, butterflies would have suggested the soul, a moth have evoked the dissolution of the fabric of life, fancy glassware and gold signified preoccupation with material wealth, while peaches, cherries, and oysters pointed toward lust).

Detail from a different 17th century Dutch still life.

Such seemingly incongruous imagery preached a lighthearted moral lesson, a mini-sermon on the inevitability of mortality and the importance of looking after the upkeep of one’s soul in preparation for the afterlife. Art historians refer to this genre as “vanitas” still life (for the theme of earthly “vanity,” as in the Ecclesiastical “vanity, vanity, vanity, sayeth the preacher, all is vanity – vanitas omni est).

These pictures’ thriving insect populations, prowling about the fruit and other objects, creates a secondary world all its own, waiting to be explored by the attentive viewer. The various parasitic insects, wilting leaves, overripe or subtly rotting grapes, a worm-hole in one of the hazelnuts – remind the viewer of the transience of even the ripest, most luxuriant life in the material world.

Even without the symbolism, Old Master still life paintings from the Dutch and Flemish Schools continue to delight viewers. My own theory about why is not that they’re so photographic – actually they don’t look like anything but themselves, and photographs can’t come anywhere near them. It’s that they’re both hyper-realistic and super-artificial all at once – like the two-fold nature of mortal life and divine eternity they signify.

Another still-life by De Heem. Note the snail slithering past the foreground oyster.

Taken together, it all transforms one corner of a dinner-table into a small, private universe – a world of silence and apparent stillness, imbued with tiny signs of life, and touched, gently, by the immutable forces of time and decay.