The brilliant Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi worked over 20 years on a series celebrating the theme of a bird in flight. As we recently noted in a previous piece on wildness in art, he never sculpted the bird; he concentrated on the animal’s movement, rather than its physical features. The process by which he did that is called abstraction.

Though considered by some an abstract artist, Brancusi didn’t intend to make meaningless or puzzling abstract art. He abstracted (simplified) the figure (the bird in flight) in order to express it poetically, as a relatable experience.

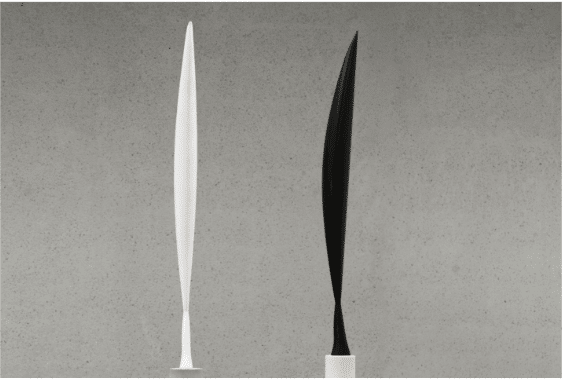

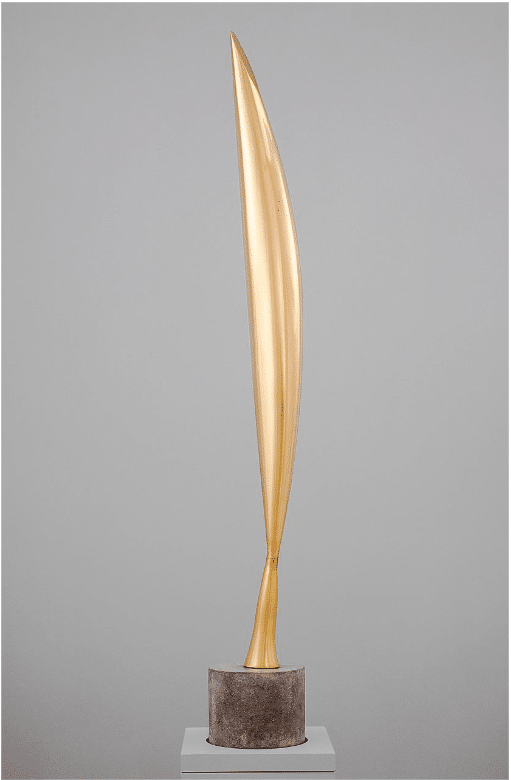

Abstract doesn’t have to mean non-representational or without form and meaning. Titled variously Flight, Bird in Flight, or Bird in Space, Brancusi’s abstract “Bird in Flight” sculptures eliminate wings and feathers, elongate the swell of the body, and smooth the head and beak to a tapering oval plane. Balanced on a slender conical footing, the figures’ upward thrust appears unfettered – matter made energy frozen in time. From the 1920s to the 1940s, Brancusi made multiple versions, including seven marble sculptures and nine bronze casts.

Abstraction in Painting

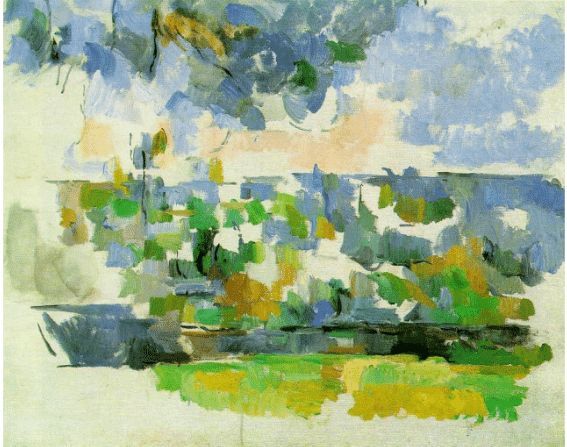

Similarly, in The Garden at Les Lauves (below), French innovator Paul Cezanne reduced the landscape to a vibrant tapestry of colors and shapes. “He was the father of us all,” Picasso said, and by “all” he probably meant himself, his friend and co-inventor of Cubism, George Braque, and the “other” giant of early Modernism, Henri Matisse. These were the originators of modern abstract art.

Cezanne was so influential because he showed that art was freer than Western painters knew it could be. Working with great imagination and classical rigor, he encouraged artists to explore color, shape and space for their own sake without having to conform to traditional, realistic principles.

Paul Cezanne, The Garden at Les Lauves, 1906, oil on canvas, 25.75 x 31 7/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Each separate mark and color of a painting by Cezanne relates to every other. The successive dabs and strokes “are meant to culminate in a sense of force field,” writes the critic T.J. Clark; as you allow your eye to skip from one element to the next and the next, “the totality is felt all at once.” Seeing Cezanne’s work in person is like feeling the sensation of the “vibrating” (Cezanne’s word) energy of nature itself. Such works exist not to imitate observable reality but to create an experience for others.

“I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty,” Cezanne might have said along with nineteenth-century American Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, “nature always wears the color of the spirit.” Stripped of individualizing features, the landscape The Garden at Les Lauves communicates the spirit of the garden in summer, just as Brancusi’s abstract sculpture communicates the sensation of flight itself rather than describing the appearance of a particular bird.

But to Get Back to the Birds…

In the Guggenheim’s Bird in Space (below), as was customary in Brancusi’s work, the brass is smoothed and polished to the point where the materiality of the sculpture is dissolved in its reflective luminosity; it’s as though the whole thing is made of light and motion. Brancusi verbalized his spiritual longing for transcendence of the material world and its constraints when he described Bird in Space as a “project before being enlarged to fill the vault of the sky.”

Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1932-1940, polished brass, 59” high, including base. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

Is there any better way that Brancusi could have depicted what flight means to us? How amazing that he succeeded in depicting not the bird but the forces and beauty that we perceive as a bird soars up into the sky. To do that, he couldn’t have just made a sculpture of a bird – he wanted to elegantly portray the feeling of the bird’s flight, and simply sculpting a bird with wings spread wasn’t going to do it.

By abstracting the subject, the artist was able to playfully represent the bird in motion combined with the way your heart suddenly does a little leap when you’re startled by the wonder and speed of a bird whizzing right past or in front of you up to the sky. The result: it’s a beautiful thing. An experience for the viewer. Granted, not all abstract art is this poetic, but when people say abstract art is meaningless trash, this is the point they’re missing.

Abstract Sculpture Today

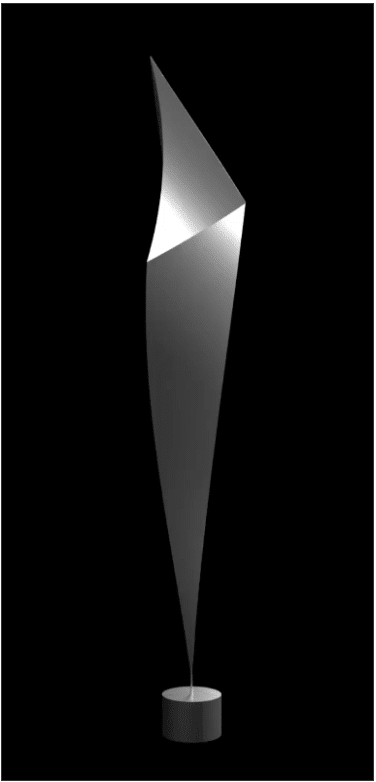

Contemporary sculptor Charles Sherman, who works in ground and welded stainless steel, has for some time been creating a series of works that consciously pay reverent homage to Brancusi’s “Bird in Flight” series.

Charles Sherman, Pirouette, stainless steel with chameleon auto paint, 60 x 12 in.

“My primary goal as an artist is to make the most elegant, simple and beautiful forms imaginable,” Sherman says. Sherman’s work-in-progress Pirouette (above), made of stainless steel with chameleon auto paint, is 60″ x 12″.

“Brancusi and I are both trying to express the sense of graceful motion through art,” Sherman says. “We are both attempting to use minimal shape to create maximum beauty. We also see our art in relation to art history, the evolution of minimalism as one of the defining traits of the modern.”

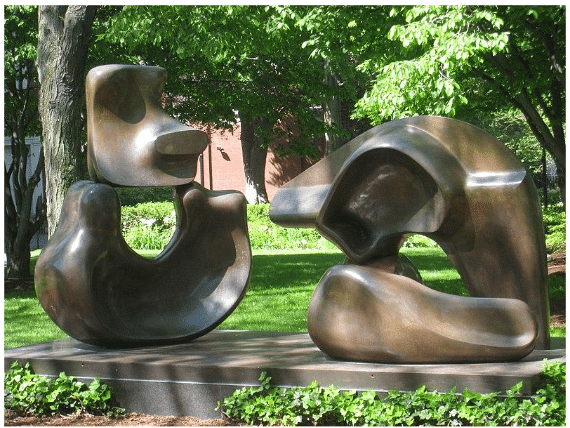

Sculpture has been predominantly abstract in the contemporary art world since Brancusi and other moderns, such as Henry Moore, whose instantly recognizable abstracted figures influenced a generation. Many of Moore’s forms blend “biomorphic” Modernist abstraction with ancient, non-Western traditions of representation, such pre-classical Mediterranean, pre-Columbian Mexican, African, or South Sea Islands.

Henry Moore, Large Four Piece Reclining Figure , Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wikipedia, photographed by Daderot and added to the public domain.

Meaningful Abstraction

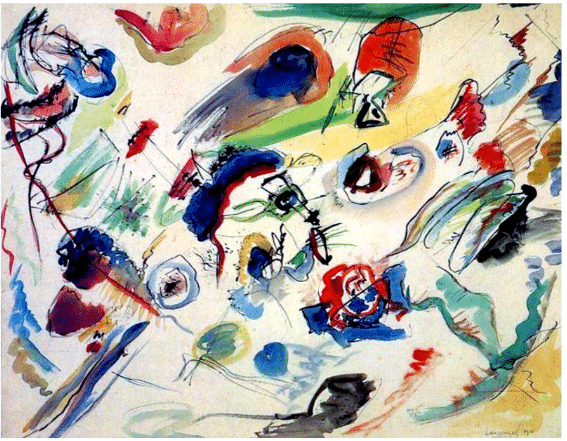

Much of the twentieth century’s abstract art was created to encompass the anxiety people felt about the rapid fundamental changes taking place in technology, science, philosophy, and global culture. Spirituality was at its heart, at least in the beginning, when Wassily Kandinsky in 1910 created his celebrated Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor), the first explicitly abstract painting ever made (except for the spiritual “diagrams” of Hilma af Klimt), which is evident in its experimental character.

Wassily Kandinsky, Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor), 1910

This is considered the first painting in which an artist approached the canvas as a kind of musical score, as if he were making a visualization of an improvised musical composition instead of a picture of anything. The links between color, energy, rhythm, emotion, and music were important to Kandinsky. He was after what he called “pure painting,” artwork that by emphasizing the expressive qualities of the material itself would provide the same emotional power as a musical composition.

And as he explained in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art, colors and shapes were for him an expression of psychological states rather than tools for the “faithful” description of reality; each color corresponded to a range of emotions. Red was agitation, blue calm, yellow aggression. “White acts like a deep and absolute silence full of possibilities,” he wrote. “The black is a nothingness without possibility, which is an eternal silence without hope, and corresponds to death.” The result of these colors acting upon each other was a lively, if jarring summary of a moment in history, a jazzy, bewildering, experimental, chaotic, rapidly urbanizing and literally electrifying time to be alive.

Abstracting the Landscape and Still Life Today

As people have learned how to approach and understand abstraction, it’s been recognized as a tool like any other. Representational and non-representational abstraction has remained a vital form in contemporary painting, even as it’s filtered down to enhance realism and impressionistic representational painting in subtle or not-so-subtle ways. For one thing, it frees you from the judgmental logical mind, if just for a moment, and lets you go wild with the paint and the color. “Abstract landscape” painters worth their salt tend to combine this freedom and wildness of method with definite intention and feeling.

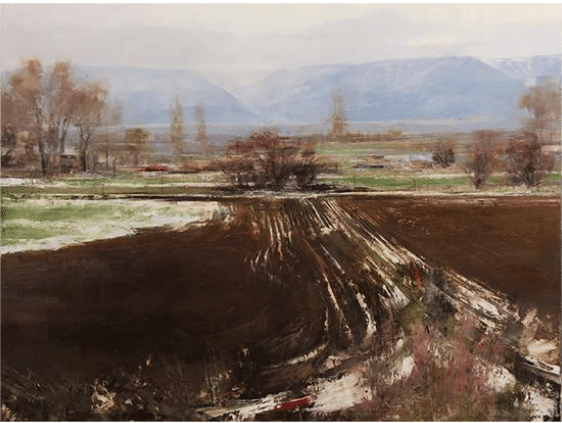

Douglas Fryer, Farm on Highway 89, oil on canvas

Artist Douglas Fryer, for example, invests his more-or-less abstracted landscapes of rural America with an intimate sense of place and mood. His atmospheric works combine gestural applications of paint, muted color tones, and abstraction with a sense of honest, lived experience rooted in the American west.

Douglas Fryer, Spring Thaw – North End, oil, 36 x 48″

In Fryer’s work, wherever it lands on the abstraction-to-realism scale, there is a kind of poetry, related perhaps to what he has called “a reflection of what is true about ourselves and what we value most in our loneliest introspection.” Fryer finds an agreeable wildness is using spatulas, squeegees, and scrapers to create his gestural surfaces.

Douglas Fryer teaches his unorthodox approach to the tools and principles of traditional landscape painting in his teaching video, Painting with Intuition.

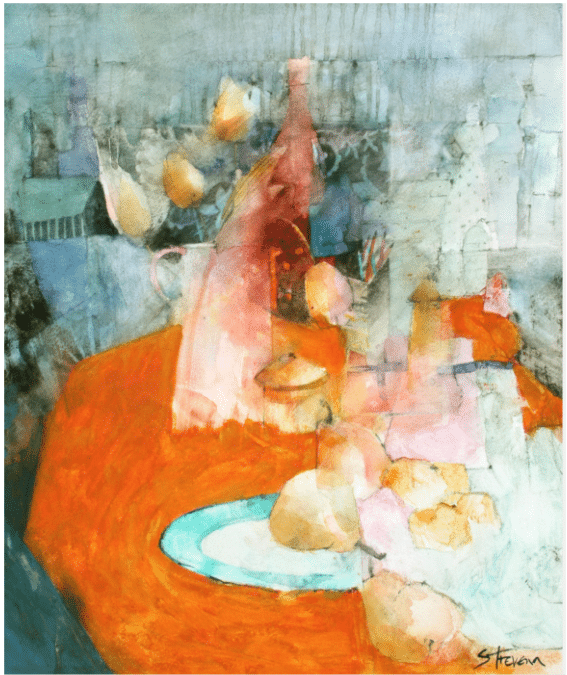

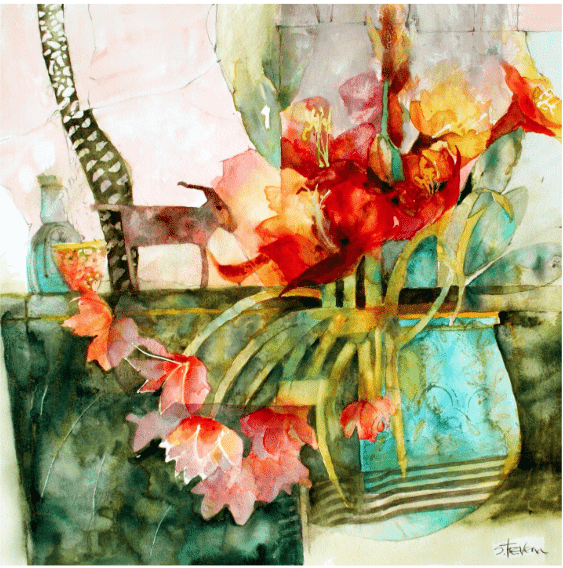

Shirley Trevena’s still lifes are largely about sensation – they’re informed by how objects such as the colors of flowers in light and space can make us feel. She’s a non-conforming painter, and she joins her wildness with wide-eyed joy and gesturally rendered abstractions of represented objects.

Shirley Trevena, Orange Cloth and Pink Jug, watercolor and graphite pencil, 45×38 centimeters.

Like Cezanne, Shirley Trevena flattens and tilts the planes (such as the tabletop and pear angles in her watercolor titled Orange Cloth and Pink Jug, pictured above) and plays with the rules of perspective to foster a freer and more playful interpretation of reality – and an exciting and vibrant colorful surface.

Choose from three different teaching videos if you’d like to learn how Shirley makes her watercolors. Browse them here.

And stay wild – and stay true.