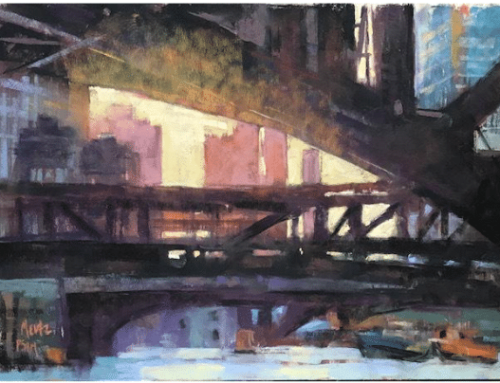

Johan Christian Dahl, Swinoujscie in the moonlight, 1840

Growing up in poverty, the son of an unambitious fisherman, left him bitter; being kept down and exploited by his first art teacher infuriated him. As it happens, a chance meeting with a well-connected man of letters touched off a chain of events that would eventually vault him to the heights of national artistic fame. Still, he died believing his vision of nature’s profoundest mysteries to be a destiny unfulfilled.

Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857) is often described as the father of Norwegian landscape painting. Though he lived and worked in cosmopolitan Germany, Norway’s natural beauty was his visionary domain.

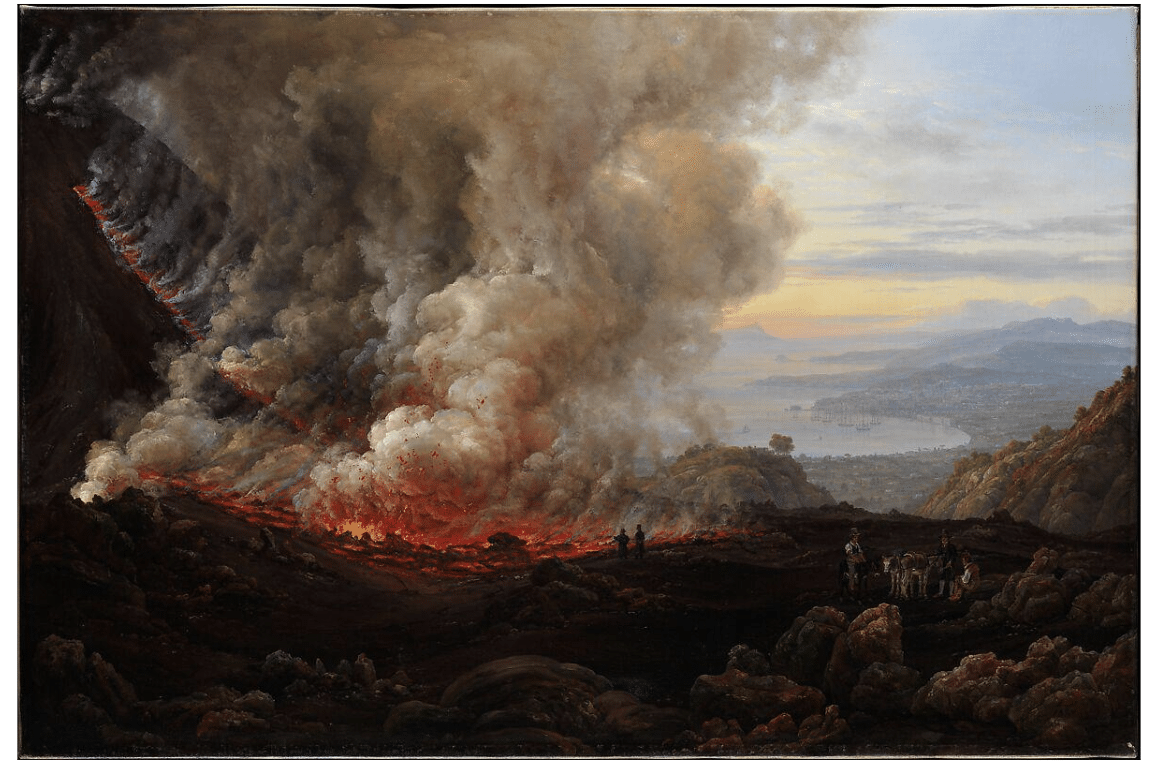

Beauty, melancholy, and the sublime stalk Dahl’s paintings of twilit cities, lonely moonrises, erupting volcanoes, shipwrecks, and unpeopled wintry distances. The scale is vast, and the natural upheavals are real. However, in his “Eruption of Mount Vesuvius” of 1821, Dahl does more than merely document the burning magma. He uses the subject to project a sense of mankind’s smallness and vulnerability in the face of the immense puzzle of existence.

Look how Dahl backlights two tiny, anonymous human figures at the rim of the volcano. What would that symbolize about man’s relationship to nature? They’re dwarfed by the earth roiled with infernal fires, the air clotted with primeval, sulfuric vapors. A tiny urban landscape fades into the primordial distance. Dahl transforms the 1822 eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Italy into a terrestrial event of near cosmic dimensions. And yet, he’s too much a realist to resist placing the work in his own time period by peopling the foreground with the two Italian guides (and their donkeys) who presumably brought him and his party to the site.

Johan Christian Dahl, Eruption of the Volcano Vesuvius, 1821

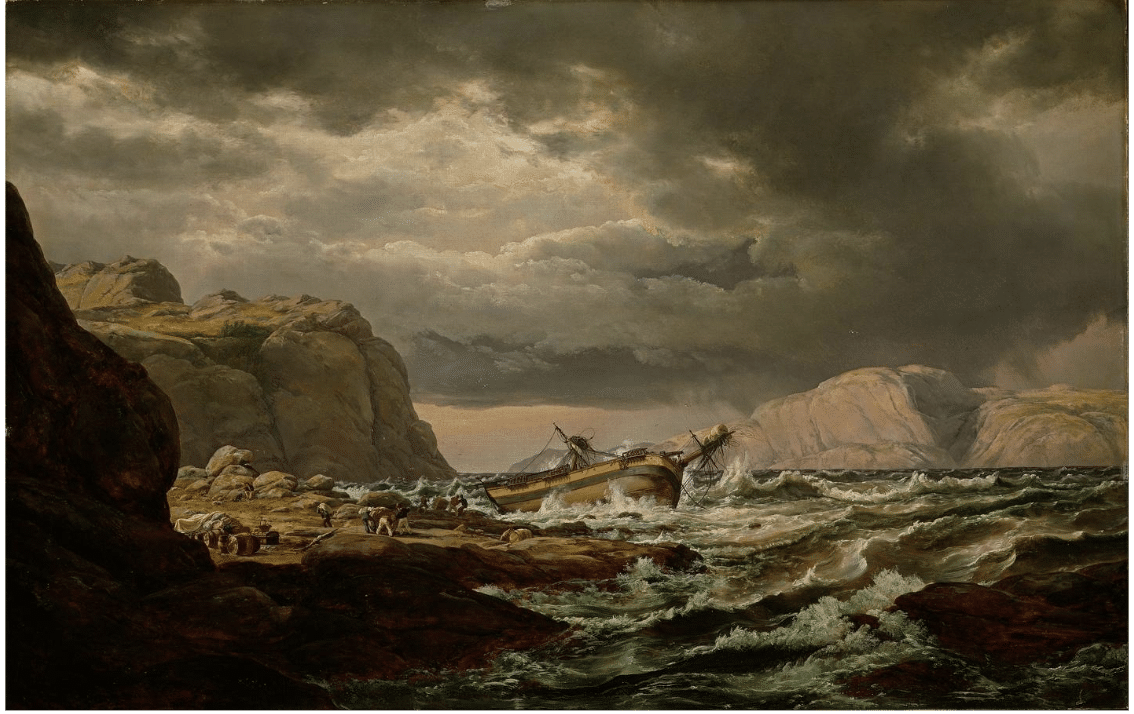

Johan Christian Dahl, Shipwreck on the Coast of Norway, 1832

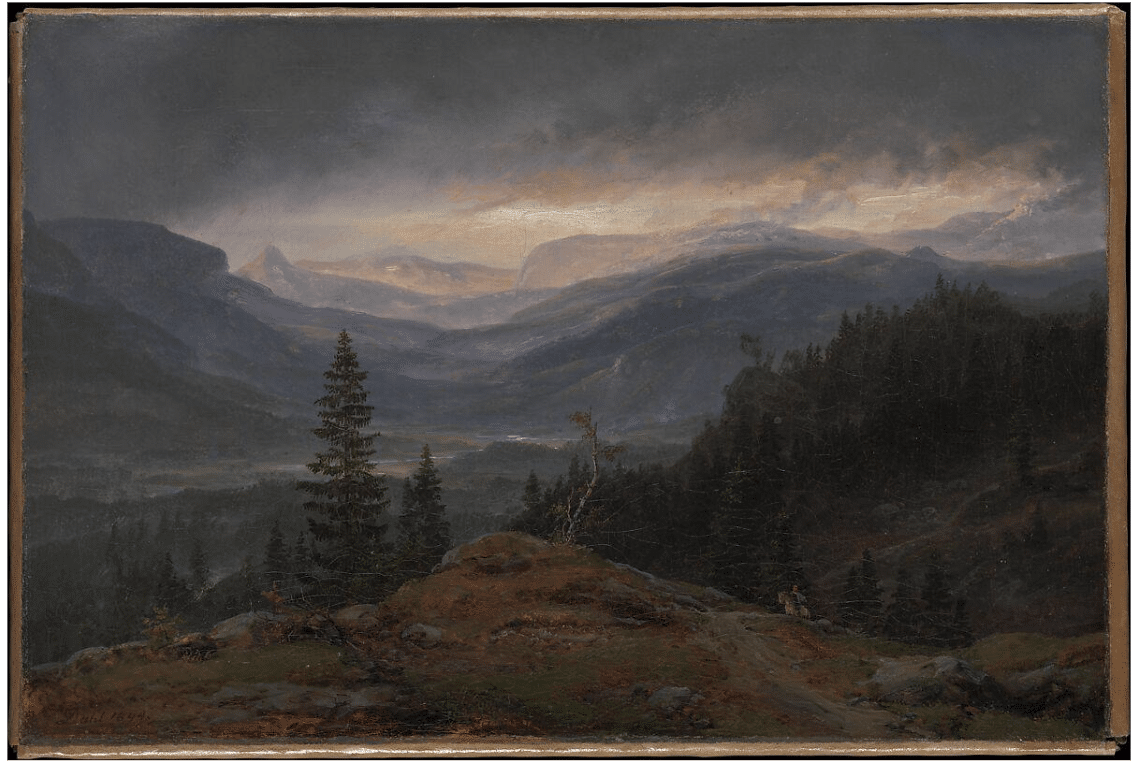

Johan Christian Dahl, Hallingdal, 1844

Such dramatic scenes, along with majestic views such as Dahl’s tamer Hallingdal of 1844 (above), loom large in Romantic painting, in Germany as well as to a lesser extend in Britain. The Romantic sensibility in landscape painting crossed the Atlantic to the east coast of the United States with British-born Thomas Cole, who would eventually be known as the “father of the Hudson River School” of American landscape painting.

More unusual though is the depiction of time in such works. For philosopher 18th century philosopher Edmund Burke, art touches on what he called the “sublime” when it depicts the extreme, the threatening, and the awe-inspiring in nature. Burke linked the sublime to associations of eternity, mortality, and the insignificance of humanity in the face of vast and indifferent Nature. The sublime as an experience, he wrote, laid waste to the ability to express it in language. Although many painters (and poets) hinted at mortality and time by using symbolic images like ruins, twilights, and sunsets in their work, Dahl is one of the few who effectively conveys the sublime sense TIME in terms of entire eras of geological and human history.

The one painting that arguably comes closest to the feeling of “eternity” in Burke’s notion of the sublime is “Winter at the Sognefjord,” Dahl’s image of an ancient standing stone (remnant of a Neolithic shrine) abandoned on the frozen edge of a glacier.

Johan Christian Dahl, Winter at the Sognefjord, February 1827

The rude stone, clearly erected by an earlier civilization, stands sentinel-like on the edge. By focusing on nothing but the vertical shard while softening everything else in the composition, Dahl evokes a profound sense of stillness over vast swathes of time as well as space.

Dahl did more than any other artist for his native country, working tirelessly on behalf of Norwegian culture. He was, for example, a key figure in the founding of the Norwegian National Gallery and of several other major art institutions in Norway, as well as in the preservation of Norwegian stave churches and the restoration of the Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim and Bergenhus Fortress in Bergen.

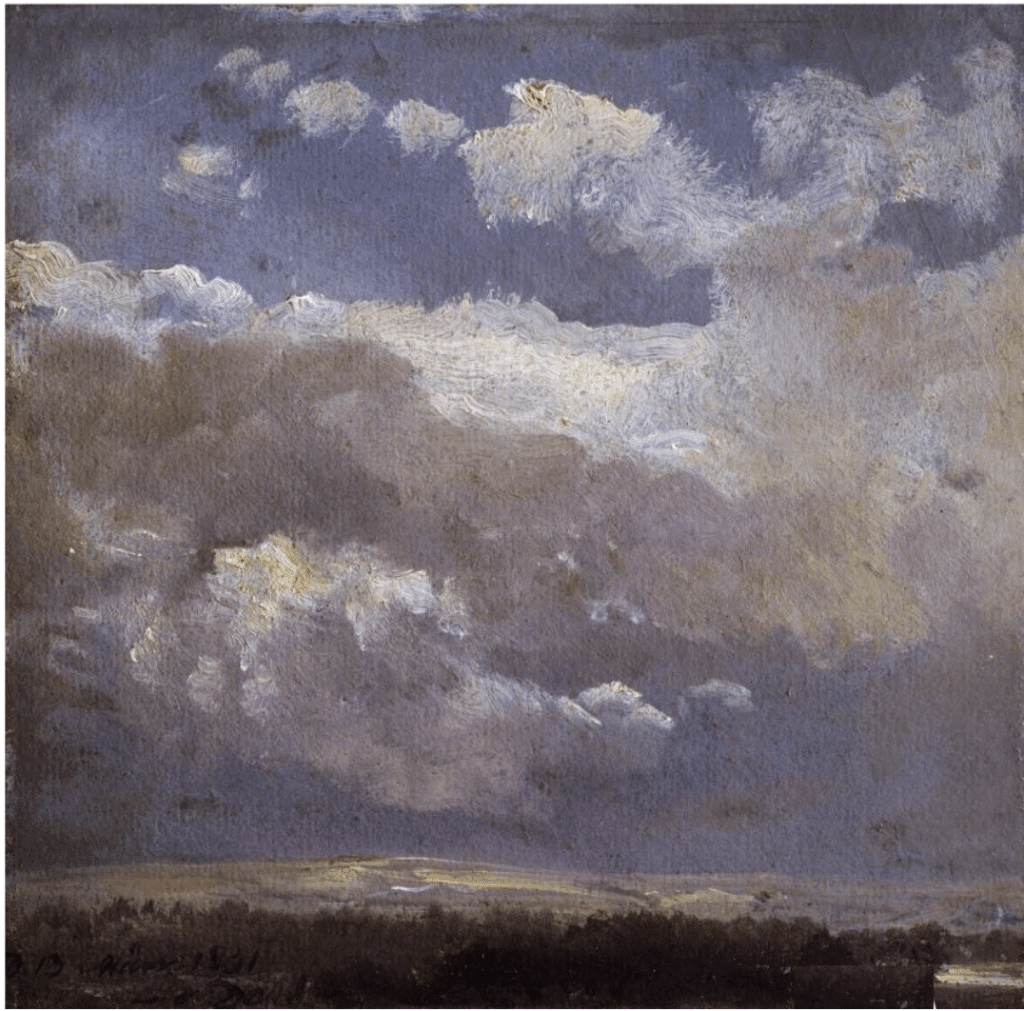

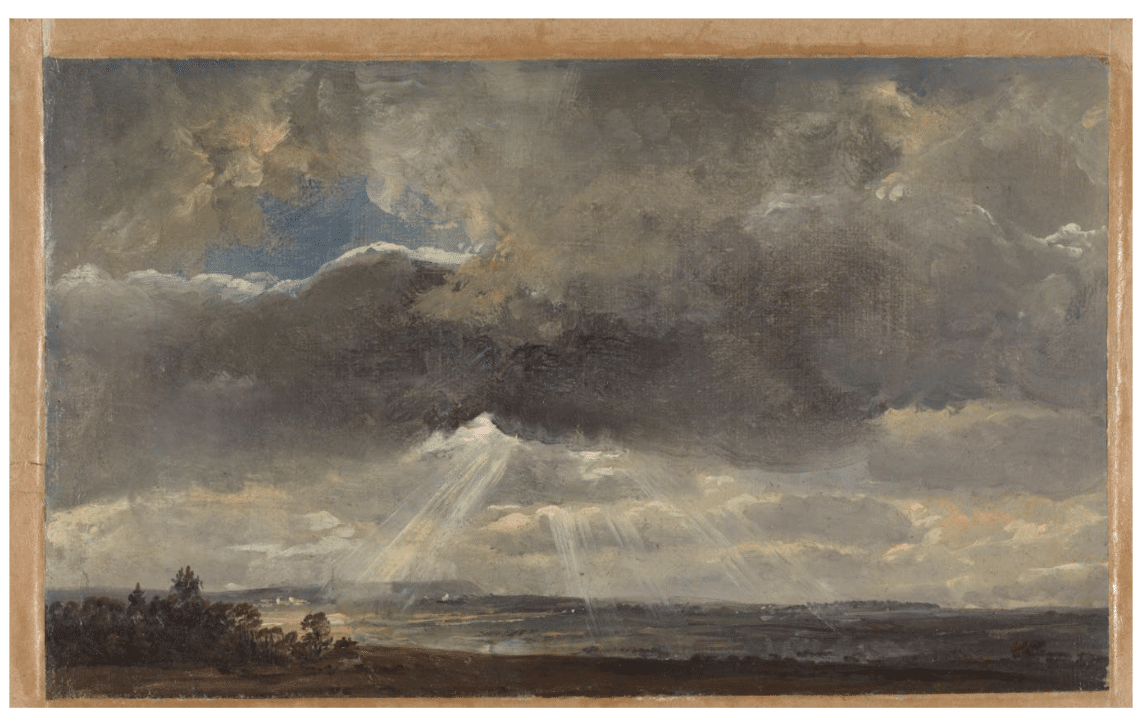

John Constable, one of the founding fathers of English landscape painting, provided a model for how an artist could work from nature and still produce deeply thoughtful and thought-provoking paintings. Constable created work that, like Dahl’s, resonates with deeper philosophical and religious themes. Dahl, just like Constable, made numerous plein air studies of clouds.

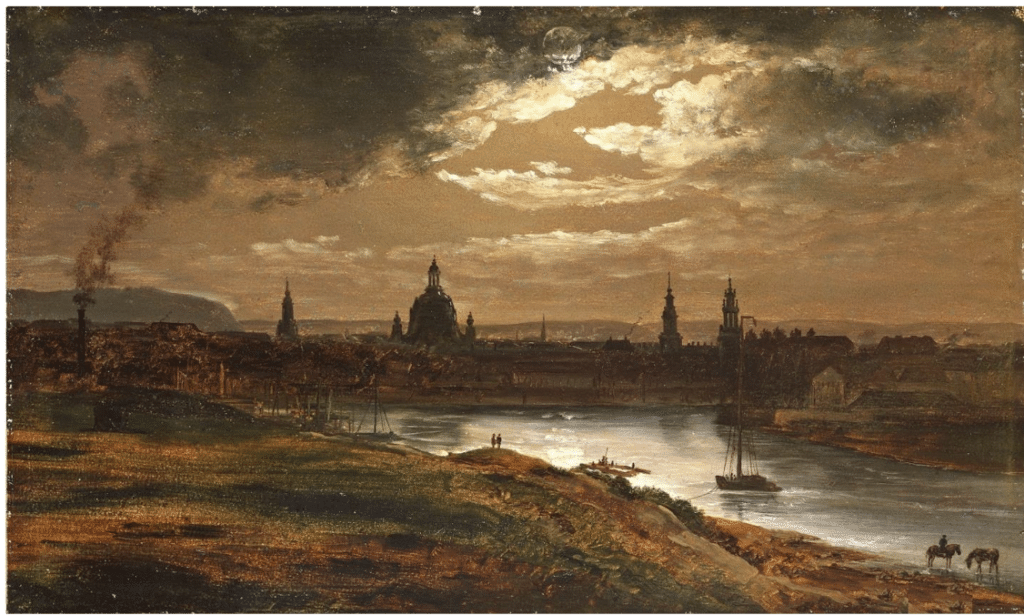

The same commitment to observation carries over to Dahl’s numerous paintings of his German city of Dresden by moonlight. Between Dahl’s 1835 and 1845 version of almost the same view, new buildings have risen and a smokestack billows rust-colored smoke that joins the nebulous clouds obscuring the moon.

Johan Christian Dahl, Dresden by Moonlight, 1835

Johan Christian Dahl, Dresden by Moonlight, 1845

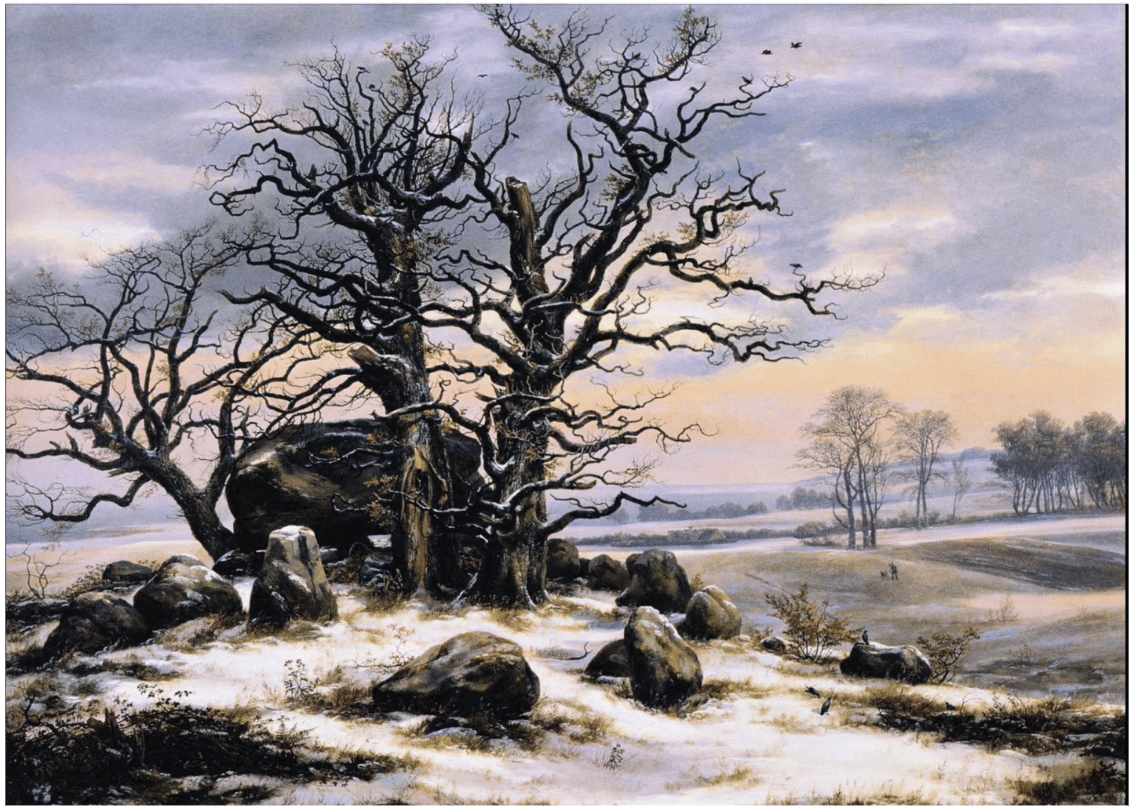

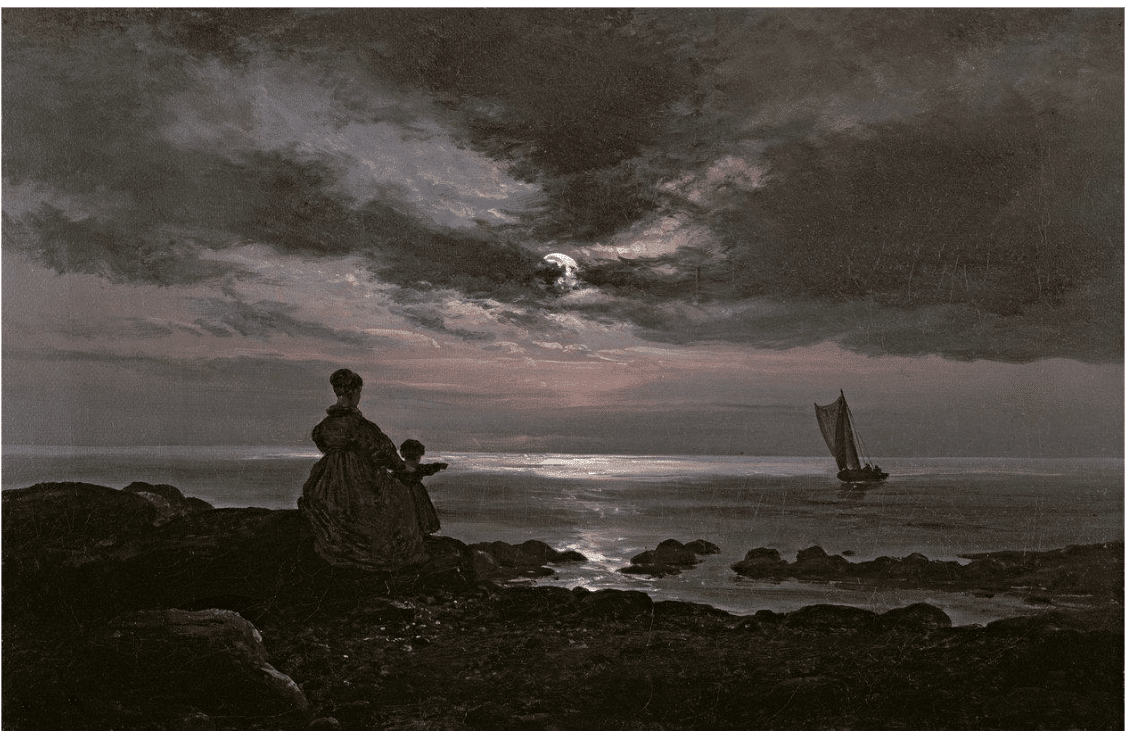

As the paintings below suggests, Dahl was influenced by his German painter friend Casper David Friedrich. There are Friedreich equivalents of both the ancient tomb amid the wildly serpentine branches clawing the air (immediately below) and the figures in shadow contemplating the rising moon over a leaden ocean (second below).

Johan Christian Dahl, Winter Landscape near Vordingborg, Denmark, 1829

Some believe Dahl to be one of the greatest European artists of all time. He was certainly the first Norwegian artist to reach the level of achievement attained by the greatest European artists of his day. It’s plain to see that although Dahl spent much of his life outside of Norway, his love for his country animates the motifs he chose for his paintings and his extraordinary efforts on behalf of Norwegian culture generally.

Still, Dahl was deeply and passionately committed to his personal vision. He never fully outran the ghosts of his early life. Dahl died believing that he could have achieved more in his work and garnered still more attention and acclaim if not for the ways his childhood and young adulthood held him back.

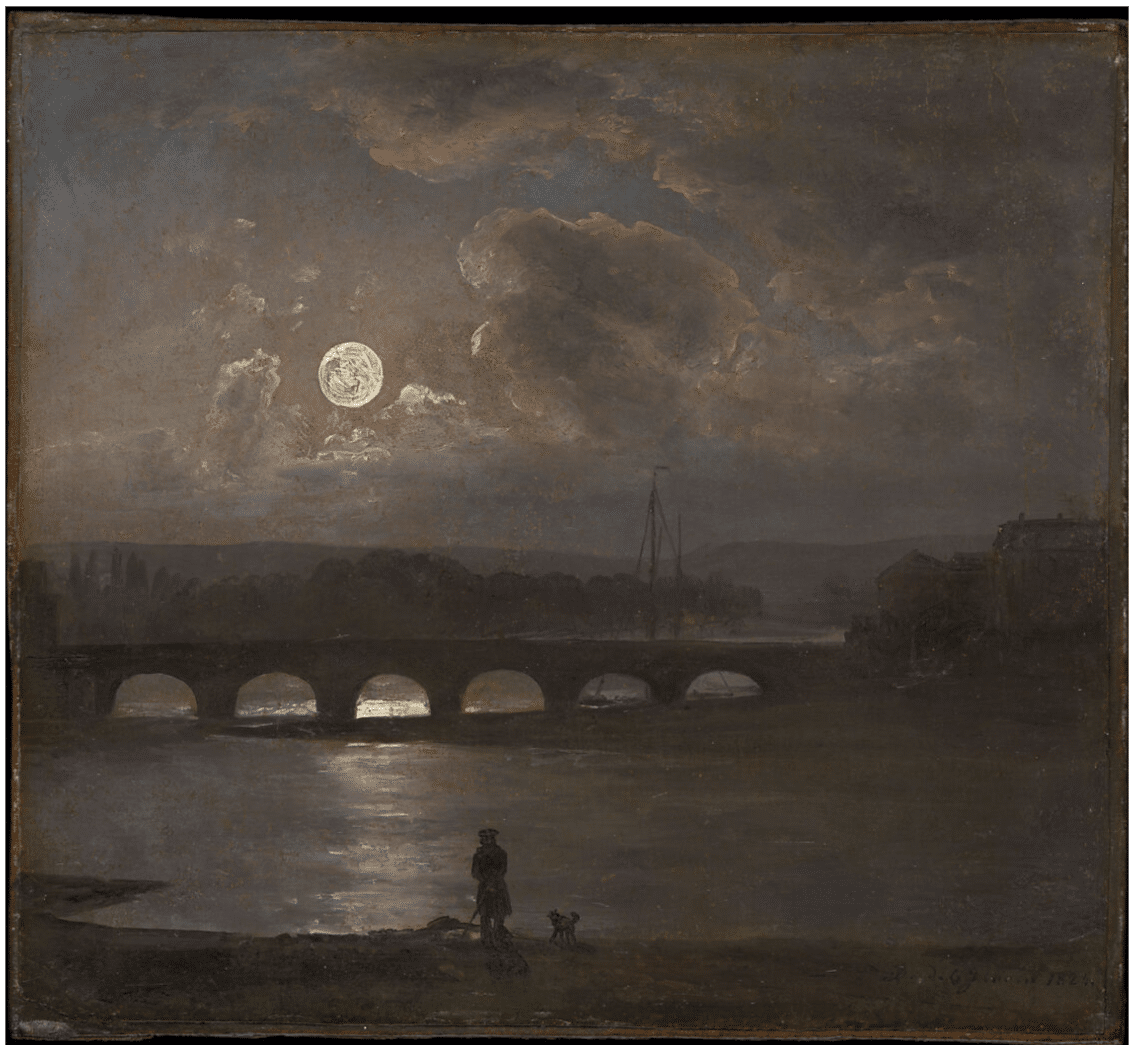

Johan Christian Dahl, City by Moonlight, c. 1830