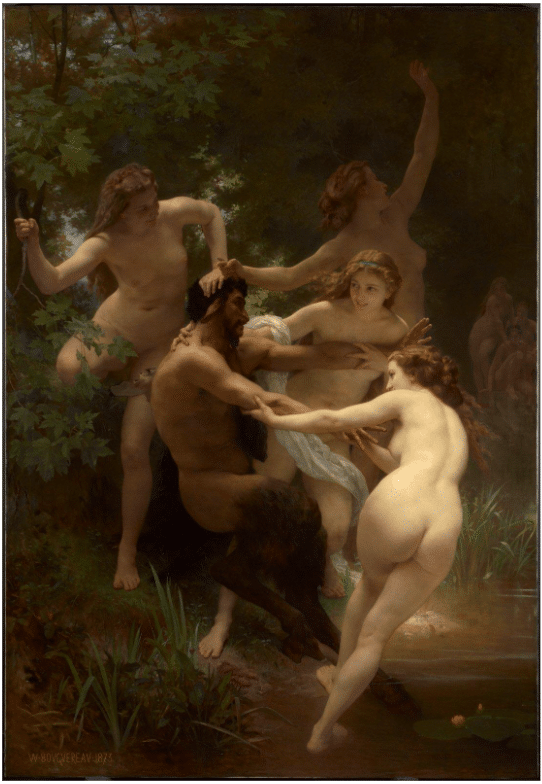

This painting, with its extraordinary history, played a pivotal role in the 21st century renewal of interest in classical realism.

If you’ve ever visited the website of the Art Renewal Center (ARC) , a non-profit organization and Web museum “leading the revival of realism in the visual arts,” you’ve seen a portion of the life-size painting “Nymphs and Satyr” by 19th century French Academician William-Adolphe Bouguereau (it’s been the ARC home page’s banner forever).

It’s an extraordinary painting with a colorful story. And as ARC’s founder Fred Ross has related, it played a significant role in the leadup to the contemporary revival of interest in classical realism. Not bad for a “risqué” picture that once hung in a New York City bar.

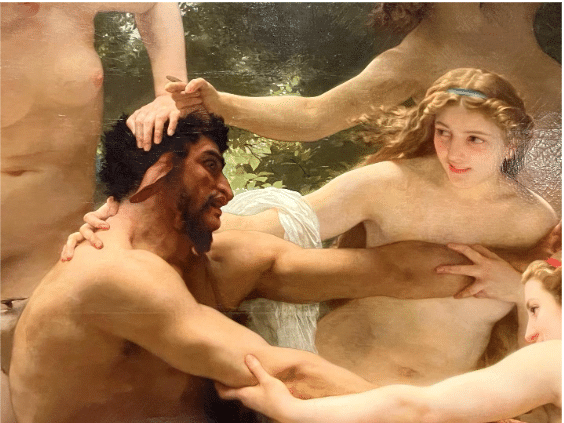

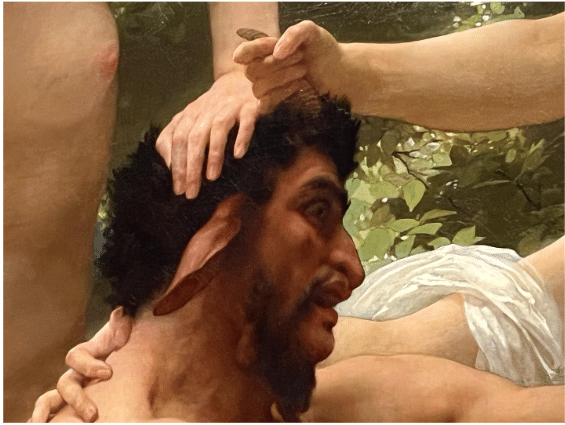

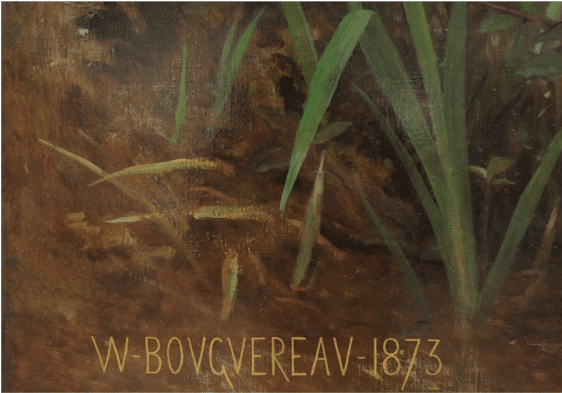

Detail: William Adolphe-Bouguereau, Nymphs and Satyr, oil, 1873.

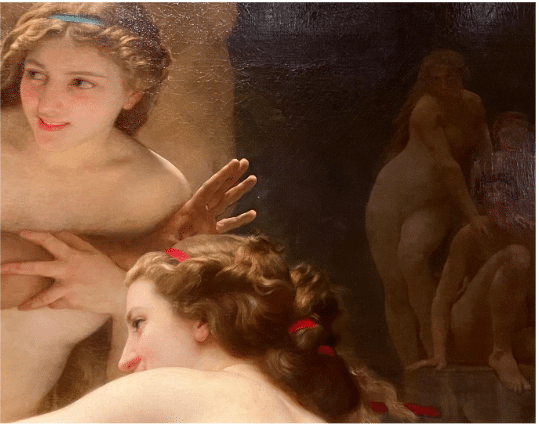

This painting’s surprising history begins with mixed reactions at the 1873 Paris Salon. The subject is mythological – a lively group of nymphs (Greek nature spirits) playfully drag a half-protesting satyr into a lake. The painting hung accompanied by a quotation from the first century Latin poet Publius Statius: “Conscious of his shaggy hide and from childhood untaught to swim, he dares not trust himself to deep waters.” At any rate, there’s no escape for our half-goat, half-man, for the nymph on the right is signaling to a second group to come help them in the cause.

Detail of William Adolphe-Bouguereau, Nymphs and Satyr, showing the second group of nymphs in the background off to the right.

While one critic at the work’s debut said the artist “had depicted a rather risky subject with charm and delicacy,” another found it little more than an impressive formal exercise, highly skilled but ultimately superficial: “where one finds the art of composition, well-ordered groups, motion, wit, and great suppleness of drawing, but which is cold in essence, empty, and leaving but a faint impression on the mind.”

Bouguereau, however, had a huge following in America, and the painting was snapped up by a wealthy traveler/collector named John Wolfe. Wolfe was something like the Gilded Age equivalent of the founder of a Lowes or Home Depot, and he was married to the heiress to a massive tobacco fortune to boot. When Wolfe sold off his entire collection of nearly 100 paintings nine years later, the owner of New York’s Hoffman House hotel bought the Bouguereau, and for the next 25 years it hung in the hotel’s Grand Saloon at Broadway and 25th Street.

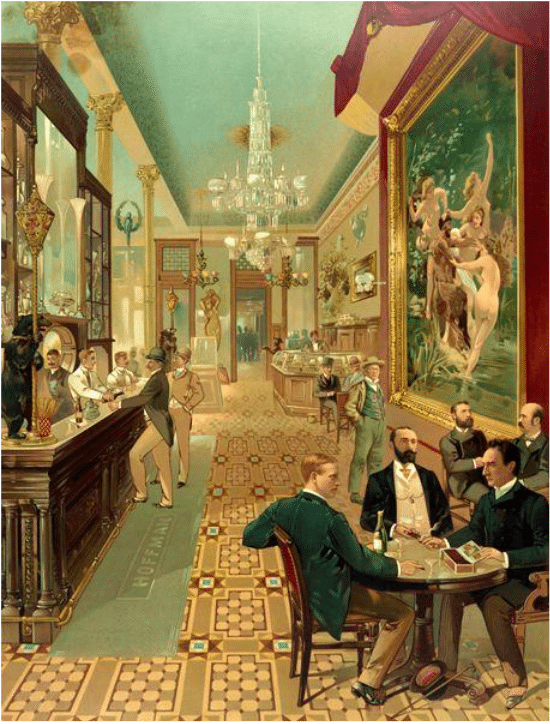

Hoffman House Bar, New York City, 1890.

There the 10-foot painting became something of a landmark, displayed beneath a red velvet canopy, lit by a crystal chandelier, and reflected in the large mirror over the bar. It had something of an aura of scandal, in part because the buyer and hotel owner, Edward Stokes, had been imprisoned for four years in Sing-Sing for the shooting of notorious speculator Jim Fiske, his rival for the love of a beautiful nightclub singer.

At Stokes’ hotel. generation of New York powerbrokers (Grover Cleveland, “Boss” Tweed, and William Randolph Hearst among them) and young men (it was all-male) from all walks of life, stockbrokers and dockworkers, world travelers and locals, rubbed elbows under its gilded frame. The Hoffman House licensed its name and the painting to advertise products like tobacco and whiskey, and a reproduction appeared inside the lid of Hoffman House Cigar boxes, carried all over the country. As a result, Nymphs and Satyr was reproduced on saloon signs and a wide array of merchandising items. Before long, the painting became a national sensation, and anyone who came to New York had to see it. One of them, a young Robert Sterling Clark, never forgot it.

When Stokes died in 1901, an anonymous buyer purchased the painting, but for whatever reason, it quickly disappeared into storage. No one saw it for more than a quarter of a century. Upon the owner’s death in 1943, his heirs put it up for sale. A flurry of interest from the press followed its reemergence into the limelight:

“A fabulous painting which scandalized the ’80s was seen in public last week for the first time since 1901. In Manhattan’s Durand-Ruel Galleries, visitors can look upon Bouguereau‘s nearly 12-ft. masterpiece (sic) Nymphs and Satyr. A quartet of ripe, naked maidens prancing around a preoccupied faun was for 24 years the despair of Victorian moralists and the delight of the clubmen who crowded Manhattan’s Hoffman House bar.”

Well, Clarke had to have it. The only way his family would let him buy it though, was if he promised not to publicly exhibit it. This he simply could not resist doing once it was his, but since he’d taken the precaution of purchasing the work anonymously, he exhibited it that way too. Now 40 years older, the wayward sons of the Hoffman House Saloon doted upon it fondly. A Mr. Willet remarked that the picture made him “feel like twenty” again, and another admirer wrote a poem for the nymphs which encapsulated their history and their continuing attraction.

To Bouguereau’s “Nymphs and Satyr”

I drank a toast to you when I was young,

And now I’m old, I’ll drink to you again;

Once you were Gotham’s pride, admired of men,

When o’er the bar, your glorious canvas hung.

You merry nymphs, of beauty unsurpassed,

Banished for years by strange decree unjust,

0ut of the darkness and the gathering dust,

Lovely as ever, you’ve returned at last!

And you, oh faun, the Naiads drag you still

Down to their pool with gleeful merriment,

They drag you down, against your struggling will,

The half-man in you fearing their intent;

I Pity you, as over you they gloat,

Yet in your place, who wouldn’t be a goat?

Brian Pendleton

Detail: William Adolphe-Bouguereau, Nymphs and Satyr, oil, 1873

Today, it is the pride of the Clark Institute in Williamstown, MA. It was at the Clark in 1977 that ARC chairman and founder Fred Ross found himself dumbstruck by a painting that, based on what he’d been taught in art schools, by all rights shouldn’t exist. As he told a Jan. 4, 2002 Portrait Artists meeting at the Salmagundi Club in Manhattan, this very work played the pivotal roll in altering his understanding of art history and led to the way to the uncovering of this entire era and ultimately to the creation of the influential ARC.

Nymphs and Satyr at the Clark Institute, showing scale.

Ross had gone to see the Clark’s collection of Renoirs, but instead he found himself “Frozen in place, gawking with my mouth agape, cold chills careening up and down my spine, I was virtually gripped as if by a spell that had been cast,” he told the Salmagundi Club. His art teachers at the time taught that “the techniques of the Old Masters had died out,” he said, giving him the impression that “nobody knew how to do anything remotely this great by the 1870’s… Years of undergraduate courses and another 60 credits post-graduate in art, and I had never heard that name.” Bouguereau and 19th century French Academic realism was that much out of vogue. Since then, of course, and with no small thanks to Mr. Ross, the era of French Academic classical realism has enjoyed increasing rediscovery and revival.

And the painting is still a show-stopper. You can’t walk in front of it like Ross did without feeling your jaw drop just a little. It’s huge, its sensuous, it’s over-the-top gorgeous, and by now it’s practically a universal symbol for the vanished world of Greek and Roman mythology as reimagined by nostalgic nineteenth-century European art and belle lettres.

According to a New York Times article published April 7, 2000, no less a progressive than the director of the Museum of Modern Art, Glenn D. Lowry, dates his interest in art to his stunned experience of the painting at the Clark as a seven-year-old. As reported by NYTimes writer Kara Ross:

“The experience helped Mr. Lowry believe in the transformative power of art and what he calls the ‘unique encounters that occur when one is fortunate to confront directly an extraordinary object.’ Mr. Lowry, as well as other museum directors, wants to broaden the opportunity for such transforming moments by providing encounters with virtual art, viewed on a computer screen and brought to the art-viewing public via the World Wide Web.”

Which is precisely what the Art Renewal Center, not without the help of the selfsame Nymphs and Satyr, has done.

Bibliography: This article draws upon Ralph Kenyon’s scholarly article “Biography of Bouguereau’s ‘Nymphs and Satyr.’” Readers can follow this link for more information.