Related > Charlie Hunter is also on the faculty of next week’s PleinAir Live! Virtual art conference, March 6-8, 2024 – join us!

As a painter, where are you on the scale of realistic representation and interpretive expression? How much are your paintings conveying information and how much are they telling stories? It’s easy for artists to get confused between the two and get lost somewhere in the middle, says contemporary oil painter Charlie Hunter.

“Conveying information is the phone book,” Hunter says. “The Song of Hiawatha is storytelling.” Ideally you’re doing both. But to tell a story, you need to be thinking about values and edges, “the unsung heroes of successful plein air painting,” as Hunter calls them.

As an expressive, low-chroma realist known for “drippy portraits of decaying American infrastructure” (his own description), Hunter is especially sensitive to values and edges and the work they can do in both conveying information and “telling stories.”

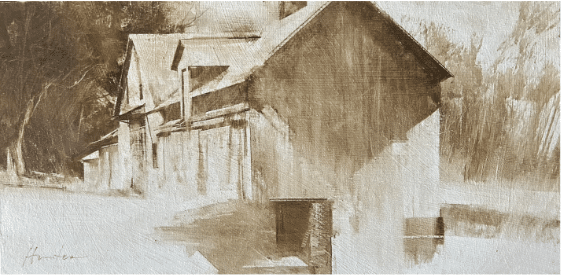

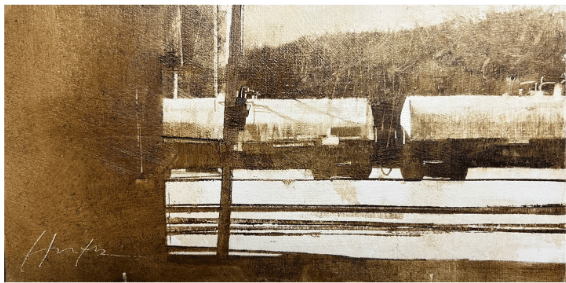

Charlie Hunter, Remnant, oil on muslin panel, 6 x 12 in.

Value is just a theoretical scale of light to dark given numbers from one to ten. Hunter recommends squinting at reality until the color goes away to better judge the interplay of light and shadow so you know where to put the darks and highlights. He’ll often include a few areas of very dark darks and light lights for contrast and intensity.

But it’s edges that arguably contribute more to tell the story. At any rate, “you need to be thinking about hard edges, soft edges, found edges and lost edges,” Hunter says.

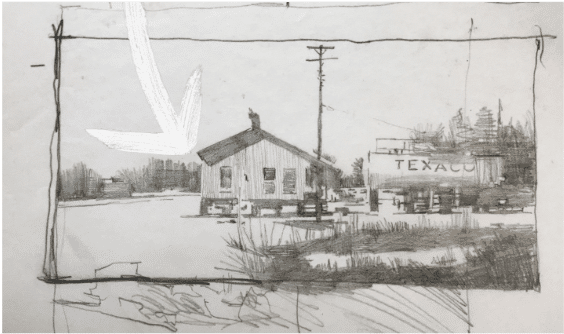

A page from one of Charlie Hunter’s sketchbooks.

Let’s look at the definition of these terms in detail. In the example above, the arrow is pointing to an area in one of Charlie Hunter’s sketches that brings together the four types of edges that Hunter names:

- Hard edge – the building’s rooftop meets the sky with a hard edge containing minimal blending.

- Soft edge – the shadow the building is casting has a soft edge, which is why it’s pretty much the last thing you notice in this area of the painting.

- Found edge – The side of the building is defined by the edge of the tree line – there’s no line drawn to convey that information. A “found” edge is where the edge of one mass defines another.

- Lost edge – that tree line closest to the building has somewhat lost edges, which artists create by blending and blurring, or as here, by bringing forms together with similar values. A lost edge is where one line or mass merges with (instead of defines) another. As Hunter defines it, in a lost edge (often for him within an area of shadow), the artist lets go of providing the viewer with the specific information and “leaves it up to the viewer and the viewer’s mind to sort it out.”

He singles out lost edges as one of the most important yet neglected areas in landscape work. “That’s one of the big counterintuitive secrets of successful plein air painting,” Hunter says. “Let go of a bunch of the edges. Let the edges take care of themselves and your paintings will seem more real than you can imagine.”

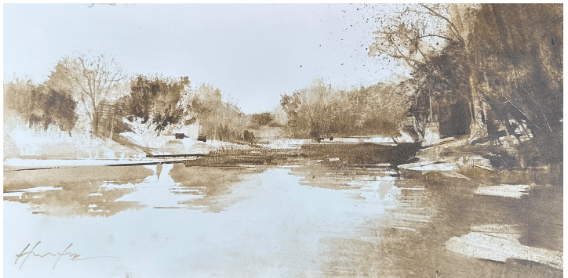

Charlie Hunter, I Sang to the Cows but the Cows Went Away, 6 x 12 in.

Indeed, Hunter suggests that plein air painters take an overall minimalist approach, letting the paint do much of the work. Besides traditional tools, Hunter uses hardware-store brushes, rags, window washer squeegees, toothbrushes and Q-tips. He urges his students not just to think about “the little bit you’re working on, but how does the little bit you’re working on interplay with the totality of the painting.”

Because ideally a final painting forms an organic whole. Getting there is all about managing and coordinating shapes, lines, values and edges within what the artist calls, “this dance across the surface.”

Charlie Hunter is a sought-after teacher, prized for his unconventional wisdom, solid technical knowledge (he’s a graduate of the art program at Yale), and his humor. Right now, there’s a special deal on a Charlie Hunter combo set, containing “Breakthrough Designs for Landscapes” and “Rule-Breaking Landscapes.” Check these videos out here.

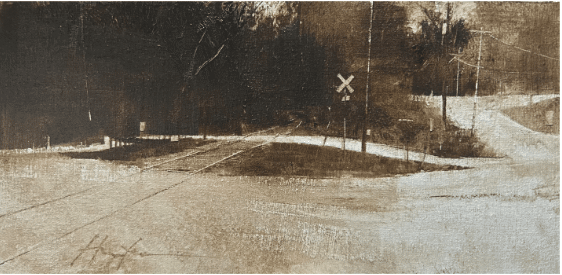

Charlie Hunter, Shadow, oil on muslin panel, 6 x 12 in

The Passing of a Pastel Legend: The Vibrant Legacy of Terry Ludwig

By Kelly Kane

Terry Ludwig, creator of Terry Ludwig Pastels, passed away on February 20, 2024, at the age of 82, leaving behind an incredible artistic legacy and a profound impact on pastel art.

Terry Ludwig

A statement released by Terry Ludwig Pastels recalls “Terry’s infectious humor and kindness that made quick friends out of strangers. He was never without a pencil and sketchpad, often drawing portraits of the many people he met.”

Terry studied art at the American Academy of Art in Chicago where he received rigorous training in classic art techniques, including color theory. Terry’s pastels gained recognition among artists for their quality and richness of color.

“Beyond his artistic contributions, Terry was a beloved figure within the art community,” the statement continued. “Known for his warm heart and generous spirit, he selflessly shared his knowledge and expertise with fellow artists, helping them hone their skills and develop their unique artistic voices. Terry’s workshops and demonstrations were always enthusiastic as he imparted his wisdom and encouraged others to embrace their creativity.”

Terry’s work

“I can’t tell you what a loss to the pastel world this is and what a loss for his dear friends and family. May you rest in peace my dear Terry.”

— Lorenzo Chavez

“Profoundly saddened today by the news of the passing of Terry Ludwig. He pioneered a brand of handmade pastels that have changed the direction of many pastel painters, including me. He was a good friend and supporter, and he will be greatly missed by our worldwide pastel community.”

— Barbara Archer

“I met Terry before a workshop we did together in Denver at PACE. He was endearing and gracious and genuine — always a smile on his face and willing to help out a fellow artist. His vision towards his line of pastels cannot be matched. He lived and breathed those little sticks of magic. Anyone who spent any time with Terry was better for it. He will be missed.”

— Karen Spangrud