By Fine Art Today

The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles is currently showing “Giacomo Ceruti: A Compassionate Eye.” The exhibition features extraordinarily sympathetic realist portraits of men, women, and children experiencing poverty by 18th-century Italian artist Giacomo Ceruti. Organized with Fondazione Brescia Musei, the exhibition is on view through October 29, 2023.

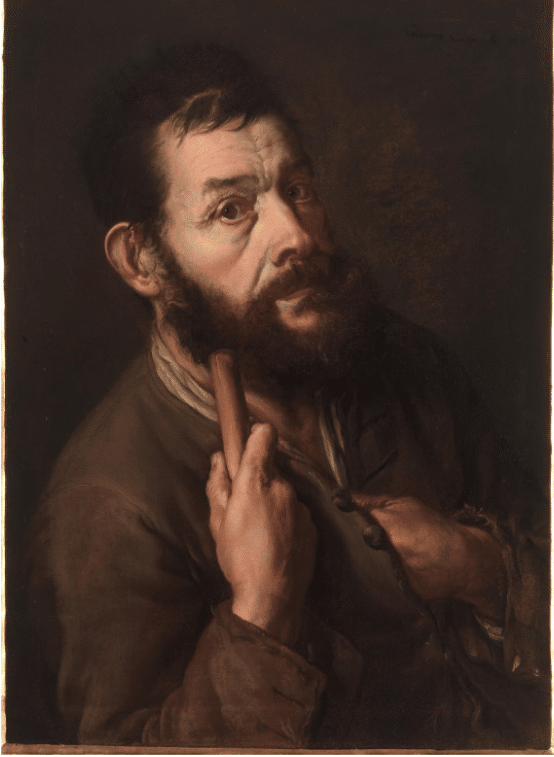

Giacomo Ceruti, “Self-Portrait as a Pilgrim,” 1737, Oil on canvas, Museo Villa Bassi Rathgeb, Abano Terme (inv. 013) EX.2023.4.1

European paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries are best known for still lifes, historical scenes, portraits, and idealized representations of religious and mythological subjects. Artists rarely depicted the poor and, when they did, mostly portrayed them as scoundrels or as figures of parody. Ceruti’s paintings stand in stark contrast, providing an empathetic view of those living on the margins of society who were often written out of history. With a compassionate eye, he conveyed their humanity and dignity at a grand scale.

Giacomo Ceruti, “Woman Mending Socks,” about 1725–1730, Oil on canvas, Museo Lechi, Montichiari, Italy, EX.2023.4.8

“Ceruti’s uniquely moving depictions of destitute and marginalized subjects are a remarkable testimony both to his distress at their suffering and to the significance of his artistic achievement in capturing their character and dignity,” says Timothy Potts, Maria Hummer-Tuttle and Robert Tuttle Director of The J. Paul Getty Museum. “Few other painters have conveyed the plight of those experiencing poverty with such vivid immediacy and compassion. I have no doubt that these powerful works will have a lasting impression on all who see them.”

Giacomo Ceruti, “Beggar,” about 1735–40, Oil on canvas, Gothenburg Museum of Art, Photo: Gothenburg Museum of Art / Hossein Sehatlou, EX.2023.4.9

Recession, war, famine, and plague were common threats that led to poverty in Ceruti’s time, especially for those who relied solely on their own income to survive. The characters he depicted belonged to what society regarded as “redeemable poor,” or those who posed no danger to others and, as such, deserved financial and spiritual aid.

Among them were women housed in charitable institutions that taught them to read and sew, such as those shown in Women Working on Pillow Lace (The Sewing School), which evokes a sense of emotional participation, as several figures look directly at the viewer amidst their daily occupations. Other protagonists of Ceruti’s paintings include elderly and disabled people begging or sitting in exhaustion, as well as men, women, and children struggling to make a living as cobblers, lacemakers, spinners, and young orphan boys forced to live on the street and work as porters.

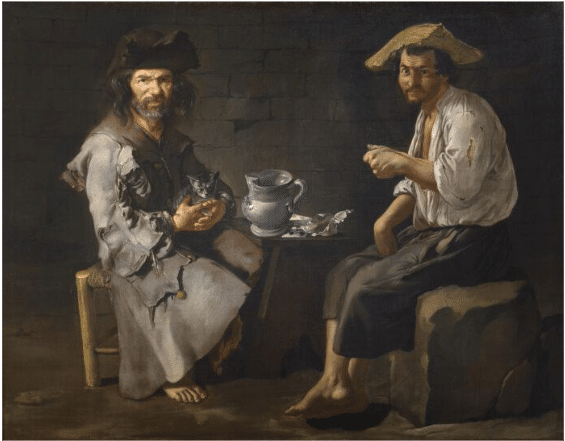

Giacomo Ceruti, “The Three Beggars,” 1736, Oil on canvas, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Madrid, long-term loan to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2004, EX.2023.4.10

The monumental size and striking facial expressions of Ceruti’s figures heighten their impact and raises them beyond traditional genre paintings of ordinary life. An example is The Three Beggars from the Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, which shows three older figures dressed in rags who appear to be struggling to survive yet retain a strong sense of mutual empathy.

Giacomo Ceruti, “Little Beggar Girl and Woman Spinning,” about 1730–1734, Oil on canvas, Private collection, Image © Fotostudio Rapuzzi, Brescia, EX.2023.4.12

“Ceruti presents his sitters with remarkably lifelike features that seem to elevate them into recognizable characters with heroic backstories,” says Davide Gasparotto, senior curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum. “Despite the challenges they faced, the anonymous protagonists of his paintings maintain a profound sense of dignity and individuality, with faces as vivid and powerful as those Dorothea Lange photographed during the Great Depression.”

Giacomo Ceruti, “Pilgrim Resting,” about 1725–1730, Oil on canvas, Private collection, Image © Fotostudio Rapuzzi, Brescia, EX.2023.4.13

Although Ceruti experienced considerable success during his lifetime, he was nearly forgotten after his death until the late 1920s, when 12 of his works were rediscovered in the castle of Padernello near the city of Brescia in northern Italy. Dubbed the “Cycle of Padernello,” these works, which are at the core of the exhibition, have perplexed scholars who had wondered about their function, patronage, and original display.

Giacomo Ceruti, “Women Working on Pillow Lace (The Sewing School),” about 1720–1725, Oil on canvas, Private collection, Image © Fotostudio Rapuzzi, Brescia, EX.2023.4.15

Ceruti’s sympathy for individuals experiencing poverty is further showcased in Self-Portrait as a Pilgrim, intentionally employing a limited color palette to portray himself as a pilgrim on a religious journey. While most artists of the period exalted their profession through self-portraits and presented themselves as elegant, cultivated gentlemen, Ceruti chose to depict himself as a humble man in simple garb with his hand over his chest, suggesting a spiritual kinship with the destitute subjects of his paintings.

Giacomo Ceruti, “Basket Porters Playing Cards,” about 1730–34, Oil on canvas, Private collection, Image © Fotostudio Rapuzzi, Brescia, EX.2023.4.21

“Giacomo Ceruti: A Compassionate Eye” is curated by Davide Gasparotto, senior curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Daniel Graves joins the tradition of artists who passed their techniques down to apprentices who would then become masters themselves in Old World Portraiture, a video that teaches the classical techniques of the masters.

‘French Curve’ Cruises to Salon Top Spot

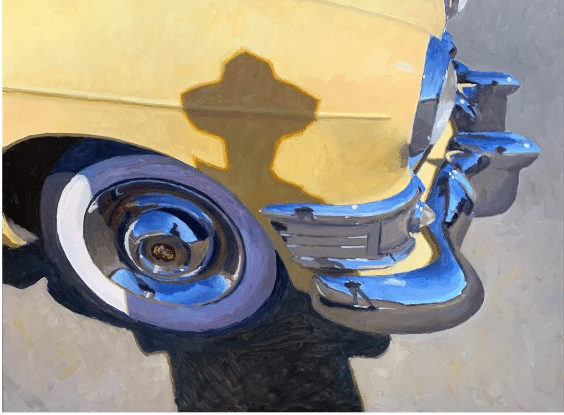

Timothy Horn, French Curve, oil on canvas, 36” x 48”

Timothy Horn has won first place overall in the June PleinAir Salon for French Curve, his 36” x 48” oil of a man’s shadow falling across the chrome-edged quarter-panel of a classic car.

The monthly PleinAir Salon rewards artists with over $33,000 in cash prizes and exposure of their work. A winning painting, chosen annually from the monthly winners, is featured on the cover of PleinAir magazine. The deadline is ongoing, so visit PleinAirSalon.com now to learn more.