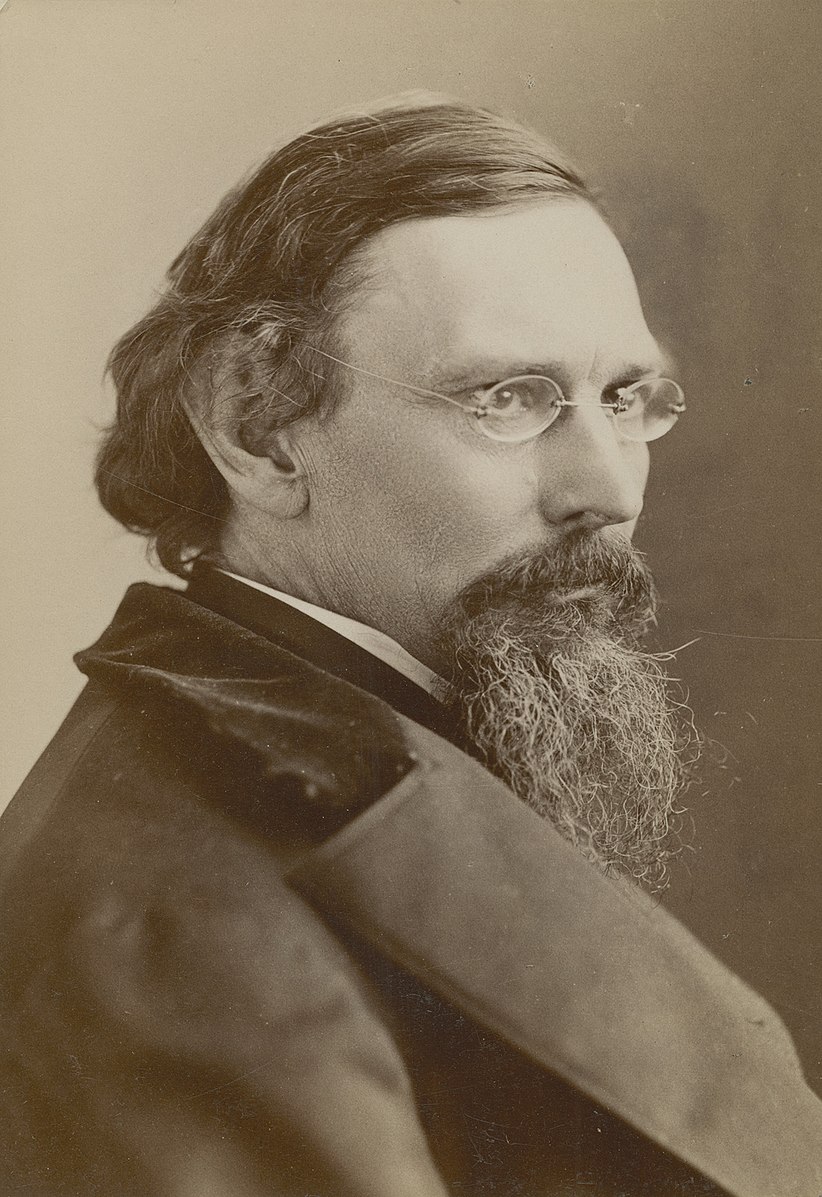

Inness

“He (Inness) squeezed a lot of raw umber on his palette, picked up the largest brush he could find, and with the aid of a medium that looked like Spaulding’s glue he went at the canvas as though he were scrubbing the floor, smearing it over, sky and all, with a thin coat of brown. The young man looked aghast, and when Pop was through, he said:

“But, Mr. Inness, do you mean to tell me you resort to such methods as glazing to paint your pictures?”

“Father rushed up to the young man, and, glowering at him over his glasses, as he held the big brush just under his visitor’s nose, exclaimed:

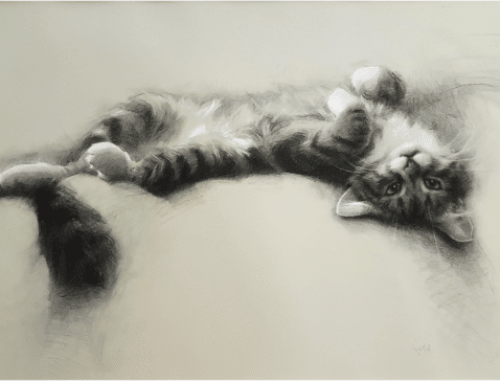

George Inness, Evening at Medfield, a tonalist painting probably toned by glazing

Glazing for Tone

I’d call Inness’ simpler, more down-and-dirty version of glazing glazing for tone. Tonalism in painting implies limited color range and maximum expressiveness through value (relative lights and darks). Contemporary masters such as Dennis Sheehan and John MacDonald have carried tonalism into the 21st century.

According to his son’s account, Inness would “cast about his studio for a likely victim, select a finished painting – a hillside in morning light perhaps – and proceed to set the sun on it, painting, glazing, and scumbling, scratching, and scrubbing” right over the already dry painting, “until he was satisfied and the morning had turned to dusk.”

BEFORE & AFTER: The same painting, first as painted alla prima, left, and after glazing, right.

Inness’ method certainly can add mood. The cool-toned marsh on the left has an okay, swooping sort of composition (mostly due to the clouds), but the colors aren’t contributing to much of a feeling. Selectively applying a yellow-orange glaze gave it an overall warmth and a more pensive end-of-day, coming-of-evening feel.

Additional shadows in the clouds add nuance and more and darker darks (olive green) in the foreground deepen the mood and add mystery. These opaque additions could be painted right into the wet layer of tinted oil. That’s another Inness thing: “painting into the soup” he called it.

Report: Art Stolen and Curator Kidnapped in Ukraine

The exterior of the Melitopol Museum of Local History in Melitopol, Ukraine, seen before the Russian invasion and reported looting

Photo from Wikimedia Commons via The Art Newspaper

Leila Ibrahimova, director of the Melitopol Museum of Local History told the New York Times last week that Russian troops along with a Russian-speaking man in a white lab coat several weeks ago tried to force a museum staffer by gunpoint to lead them to the museum’s trove of Scythian gold, which had been hidden for safekeeping. She refused, but they found it nonetheless. The curator, identified by Crimean Tatar activist Eskender Bariiev as Galina Kucher, was released but then kidnapped again and has not been seen since, according to a story in The Art Newspaper.

Melitopol’s mayor Ivan Fedorov, who was briefly kidnapped in March and disregards a Russian collaborator installed in his post, said in a Facebook video that “our local history museum is being completely looted and the history of Melitopol is being completely robbed by the Russian occupiers.” Fedorov warned that the Scythian gold is “at risk of being taken to Crimea,” which is near Melitopol, and which was annexed by Russia in 2014.