They say, “pick your battles,” so I’m picking this one. Edward Hopper’s paintings are full of meaning and emotion and I’m tired of hearing people say otherwise. You can “read” a good painting just like a good book, and there’s a heck of a story going on in Hopper.

A stoic prone to long silences, Hopper stayed tight-lipped about his art, insisting “it’s there on the canvas.” Allegedly he once said, “all I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house,” and some people have taken this to imply there’s nothing hidden or deep about his paintings.

Obviously this is total nonsense, and it’s always annoyed me because it’s so patently false. OF COURSE there’s tons of content and feeling in Hopper. He’s the arch-priest of all that’s hollow, lonely, and hidden in the deserted hotel lobbies, by-passed gas stations, and struck-dumb storefronts of the fractured American dream.

“I’m After ME”

What he actually seems to have said is, “there was a sort of elation about the sunlight on the upper part of a house,” which is very different, because “elation” betrays the painter’s investment in, and feelings about, what he painted. In fact, once when someone asked him what he was after in his paintings, he answered, “I’m after ME.”

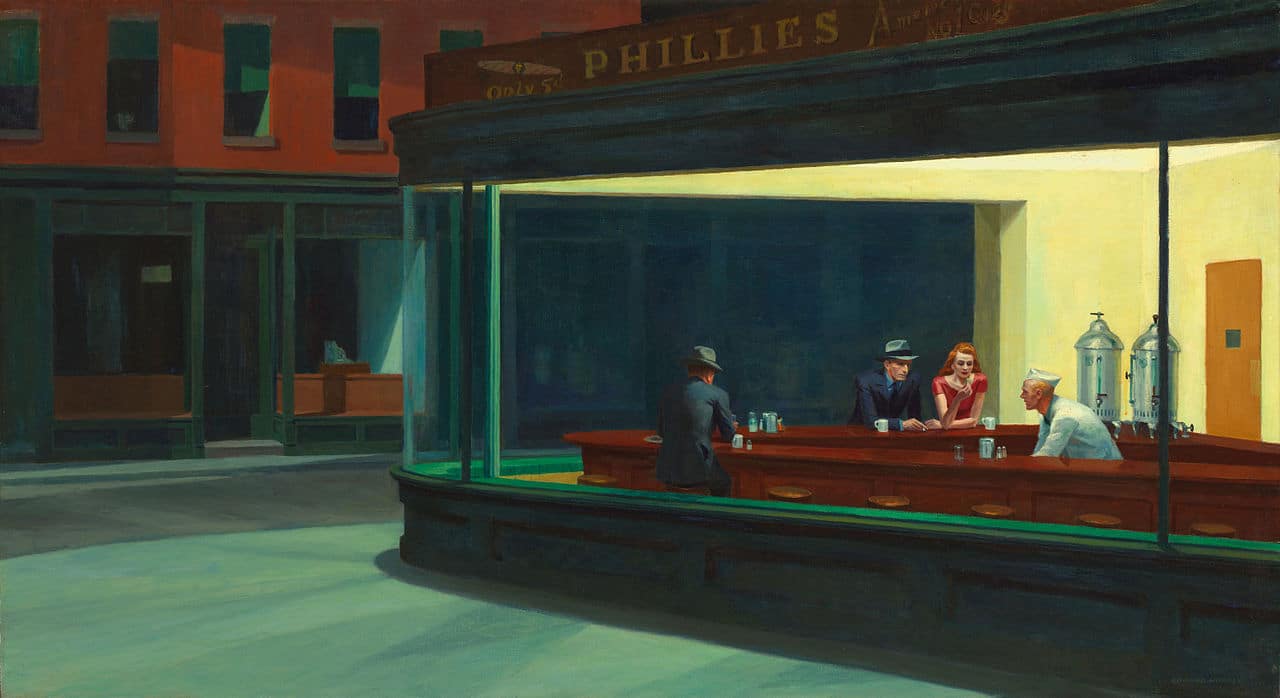

Nighthawks, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, is so of a type that many believe he based the painting on an actual diner in New York City’s Greenwich Village (specifically, where Greenwich Street meets 11th Street and 7th Avenue, an area called Mulry Square). Not so.

In fact the reference for the painting was an all-night coffee stand. “I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger,” he said. “Unconsciously, probably,” he added, “I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” Boom – and there you have it.

How does an artist like Hopper paint loneliness? For one thing, if there are people at all in his pictures, there’s usually just one, lone, lost-looking individual. If, as in Nighthawks, it’s two or more, they’re isolated, oddly lit and de-personalized, staring down, past, or away from each other. If there’s a road, it’s passing us by, disappearing out of the canvas like a bus we’ve just missed. If there’s architecture (always), it’s angular, cropped, and often strict and repetitive. Then there’s the light.

Art historian Avis Berman has called Hopper’s paintings “minimal dramas suffused with maximum power…. stark yet intimate interpretations of American life, sunk in shadow or broiling in the sun.” Hopper’s light alternately buries his people and places in dark tones and blanches them with merciless daylight or high-watt artificial illumination.

If Hopper is a realist, it’s not because of his hard-won draftsmanship, but because of how he captures aspects of our experience so authentically that, in Berman’s words, “we can hardly see a tumbledown house near a deserted road or a shadow slipping across a brownstone facade except through his eyes.”

“Great art,” Hopper also said, “is the outward expression of the inner life of the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.” Consider the record put straight.

Meanwhile, here in the 21st century, Hopper’s haunting personal vision resonates more strongly than ever.