Claude Monet loved to paint the sea, and a quick study of some his best as well as some lesser-known paintings of the ocean can teach practicing artists sound fundamental skills when diving into a seascape. We’re looking at:

- Horizon lines

- Color

- Composition

Horizon lines – hard-edged or blended – can make or break a seascape. There are two main dials to turn here, 1. blending the edge between sky and sea on the canvas (if you’re using oils) and 2. mixing closer or more contrasting values and testing them on your palette.

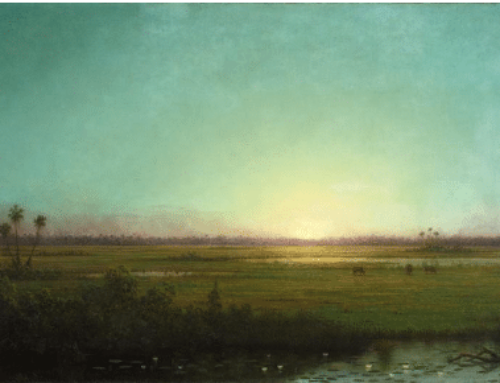

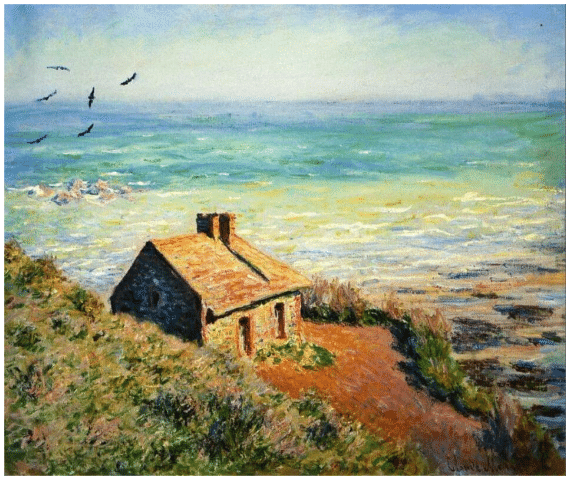

However you choose to do it, softening the line between the sky and the ocean creates the illusion of depth by opening up the space in your painting’s background (which corresponds to what we see as we peer across the ocean into the distance). In the painting below, Monet has not blended the horizon’s edge (except for contrast when it goes behind the rockface); instead he has adjusted the values of the water and the sky to be close enough to each other to push the line between them into the distance.

Claude Monet, The Customs House, Varengville, 1882

On a subtler note, the transition between ocean and sky also helps set or support the mood of piece, as in the sun-washed and wistful “Customs House” above.

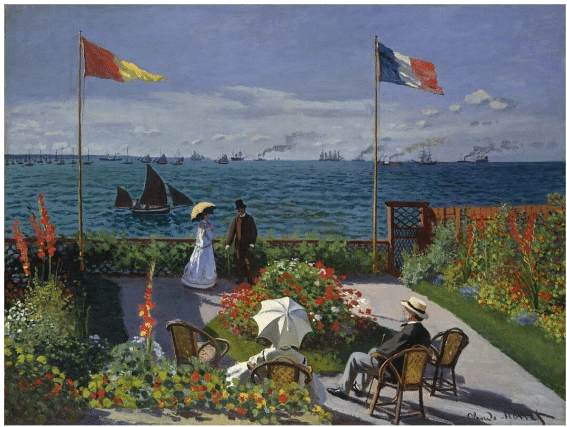

The harder the horizon line the more attention it calls to itself, flattening the illusion of depth. In his famous Jardin a Sainte-Adresse, Monet deliberately flattened the picture plane and used a hard-edged horizon line (reflecting the strong influence Manet had on him at the time). He had a good reason; because he wasn’t really “painting the sea” so much as going for a startlingly modern and edgy painting of a non-traditional motif: contemporary French bourgeois life.

Claude Monet, Jardin a Sainte-Adresse, oil, 1867

In the painting titled Jardin a Sainte-Adresse, the horizon line’s true role is to be in relation to the other broad flat geometric shapes in the manner of (in 1867) still undreamt-of abstract art.

Color Is the ocean blue? Is the sky? They really don’t have to be, but assuming they are, what kind of blue(s) are we talking about? Is it a hot Mediterranean blue? A briny blue green? A northern Atlantic gray-green-purple blue? And how dark or light will it be (how much visual weight will you give it)? Here’s where knowledge and practice of color-mixing and values comes into play.

Now, does the color of the sea have to match the sky? You would think they would, as the water is merely getting its color by reflecting that of the sky’s, but in practice often they don’t, and on paintings that’s usually best if just for the sake of variety.

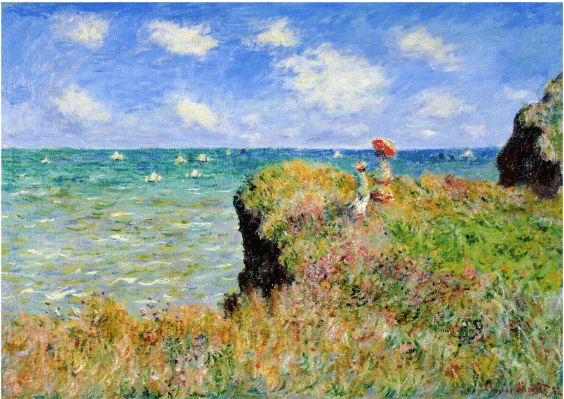

Claude Monet, The Cliff Walk at Pourville, 1882

So the short answer is no (look no further than any of the Monets in this article), BUT: unless you’re deliberately being dramatic or “modern” like Monet in his Degas phase, sky and sea should probably more or less relate in a kind of harmony (call it a “sympathy”) with each other. This you achieve by including some of the same colors in both of them.

Composition – What composition, right? While it may seem just a matter of big shapes and parallel lines, you still have three basic choices here: are you going to put the emphasis on the sky, the sea, or the shore? This choice too can make or break your painting; refuse to make it and you risk losing focus and impact. So at the outset you should ask yourself what you want this painting to be “about” – do you want to show something happening in the sky, at sea, or on the shore? Consider adjusting the height of your horizon line accordingly.

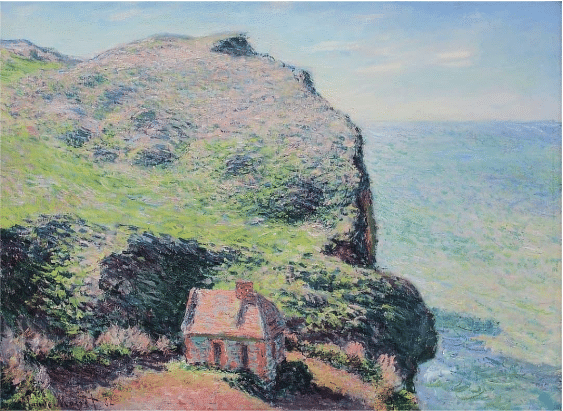

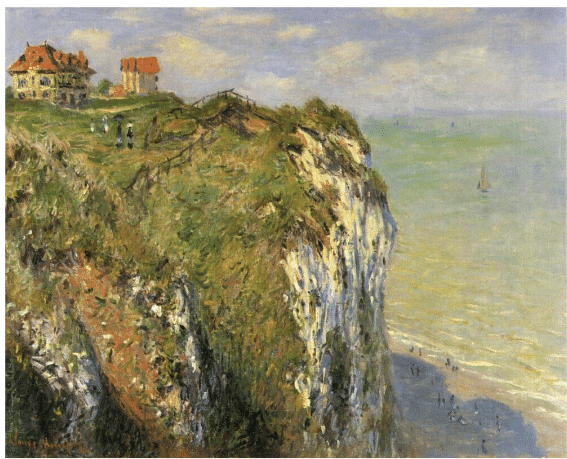

Is the focus up front or further out? If the goods are mostly in the foreground: raise the horizon way up top to keep distraction to a minimum, as in these:

Claude Monet: “Cliffs near Dieppe” (1882) Note the minimalizing value-matching and edge-blending at the horizon line.

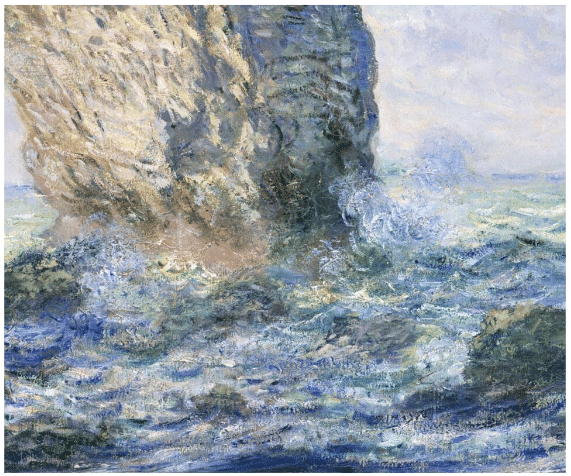

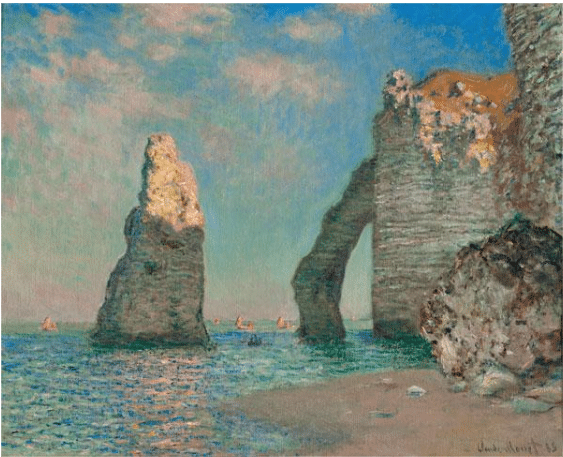

Or lower it if the focus in on the foreground and you want us standing there looking up at very tall, close objects such as cliffs or large rock formation, as Monet does here:

Claude Monet, The Cliffs at Etretat, 1885

If you’re wanting to emphasize the sense of distance and open space, whether you place the horizon line in the lower third or the upper, getting a soft transition between them, using wither value or blending, is key (see “Horizon Lines” above).

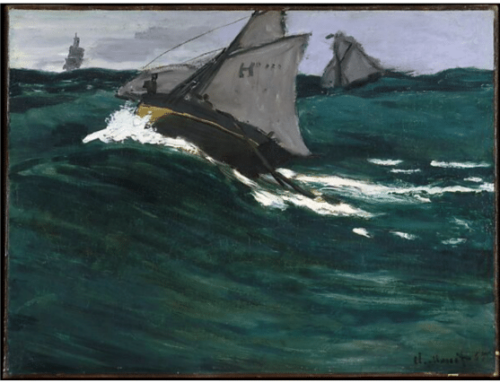

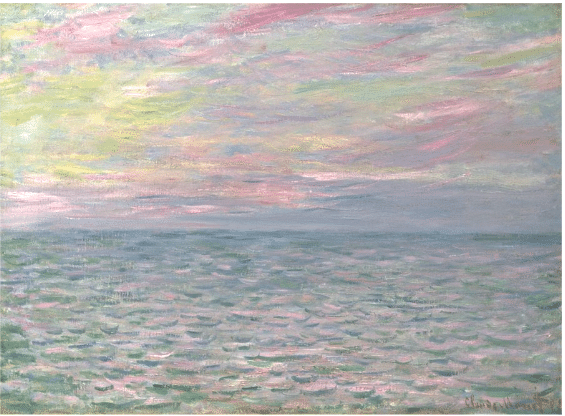

Go ahead and near-center the horizon line if you think you can guarantee enough interest in the color, texture, design, movement, and variety between two large swaths of stacked-up rectangles to keep the interest of the viewer. Monet certainly manages it; in the one below, it’s his magic with color (and the wonderfully subtle “V” shaped perspective lines of the boat’s wake receding toward the horizon) that win the day.

Claude Monet, Sunset at Pourville, Open Sea, 1882

Happy beach days, everyone.

Claude Monet, Fisherman’s Cottage on the Cliffs at Varengville, 1882

Mastering the Sea

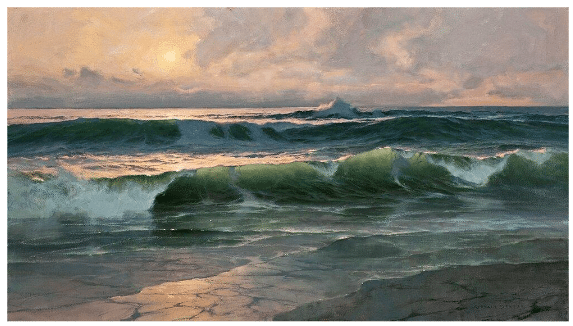

Donald Demers, Waves at Sunset, oil

Donald Demers is an internationally renowned artist and a master at painting the elusive characteristics of the sea. His video, titled Mastering the Sea, details a reliable method that allows you to consistently paint the sea with accuracy and emotion. In this video, he walks you through a complete demonstration that includes not just technique but key facts about how the sea moves and the water’s relationships with light, clouds, rocks and sand, wet or dry. Check it out here.

There’s also a bundle of two on sale that together constitute a real masterclass for painting the ocean with accuracy, passion, and life. Check that out here.